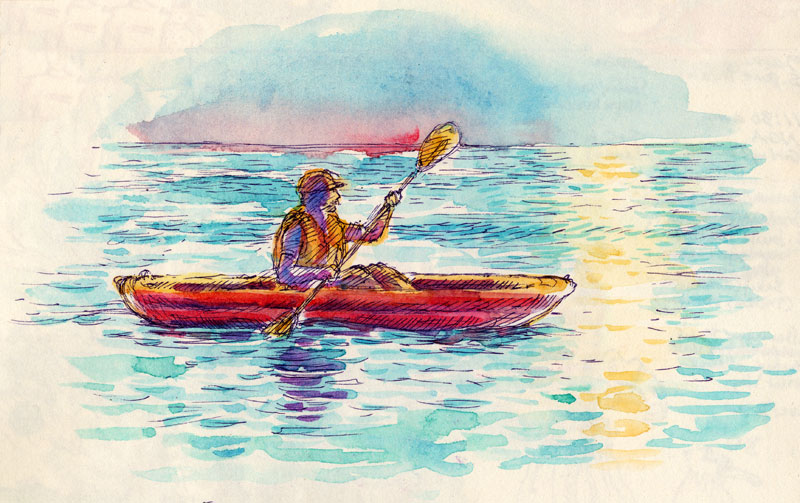

It’s ironic that my husband’s birthday falls in December, because he is a sun-worshipping beach-loving guy. So on this day I post a sketch I did of him the summer that he bought and launched his inflatable kayak. This is what I would REALLY like to give him for his birthday: warm, happy hours gliding through the ocean at sunrise and sunset, gazing at dolphins, dreaming.

Month: December 2010

This World is not Conclusion

Today is the birthday of Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), and it is difficult to choose from among her rich and relentless outpouring. But here is one to ponder as we move inexorably, yet hopefully, toward the darkest time of year.

This World is not Conclusion. A Species stands beyond — Invisible, as Music — But positive, as Sound — It beckons, and it baffles — Philosophy — don’t know — And through a Riddle, at the last — Sagacity, must go — To guess it, puzzles scholars — To gain it, Men have borne Contempt of Generations And Crucifixion, shown — Faith slips — and laughs, and rallies — Blushes, if any see — Plucks at a twig of Evidence — And asks a Vane, the way — Much Gesture, from the Pulpit — Strong Hallelujahs roll — Narcotics cannot still the Tooth That nibbles at the soul ——Emily Dickinson

Paradise Lost

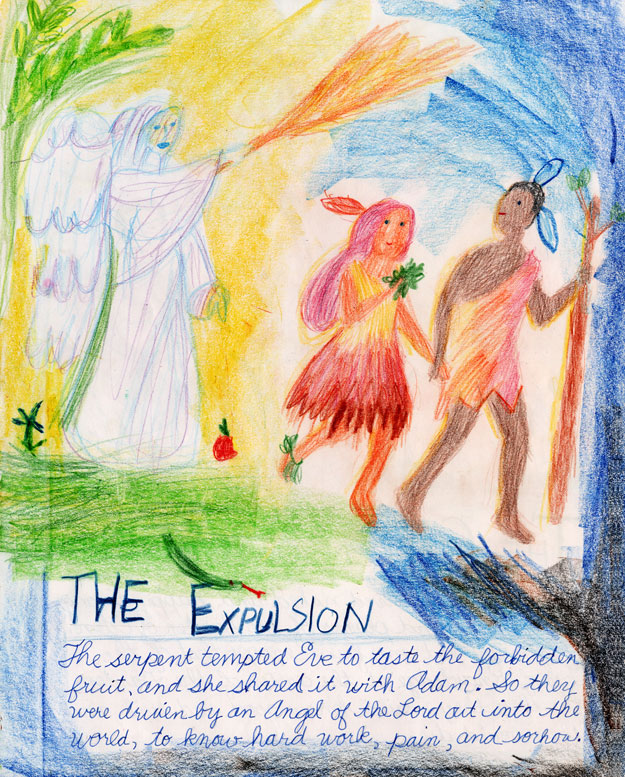

Today is the birthday of John Milton (1608-1674), and in his honor I post the closing lines of his masterpiece Paradise Lost, along with a drawing by my daughter from our homeschooling Old Testament block several years ago. It’s not exactly a match, but I couldn’t resist.

Her drawing belies the solemnity of the poem. Adam and Eve actually look rather pleased at their departure from the Garden of Eden.

In either hand the hastening angel caught Our lingering parents, and to the eastern gate Led them direct, and down the cliff as fast To the subjected plain; then disappeared. They, looking back, all the eastern side beheld Of Paradise, so late their happy seat, Waved over by that flaming brand; the gate With dreadful faces thronged, and fiery arms: Some natural tears they dropt, but wiped them soon; The world was all before them, where to choose Their place of rest, and Providence their guide: They, hand in hand, with wandering steps and slow, Through Eden took their solitary way.—John Milton

Imagine

—John Lennon

St. Nicholas Day: Part 2

(continued from December 6th)

However, after Livingston’s death in 1829, Moore quietly wrote to the newspaper asking if they knew the author of the popular verse, “The Night Before Christmas.” When the editors replied that they did not, as it had been published anonymously, Moore claimed authorship, saying that he had been “too embarrassed” to claim it previously. His surprised and delighted family, and many others, came to believe him.

When Moore later included it in a book of “his” poetry (which actually included several other poems later revealed not to be Moore’s own—tsk, tsk), the astonished Livingston children protested. But would a rich and respected theologian actually LIE about his work? Not to be believed. So nobody did. Livingston’s papers, including his handwritten copy of the poem with its changes and crossed-out passages, had perished in a fire, and the children had no evidence beyond their personal knowledge. Moore later churned out several handwritten copies of his own (not exactly matching Livingston’s original, but what the heck) which eventually sold to collectors for big bucks.

End of story… until the arrival on the scene of Donald Foster, an English professor at Vassar and a well-known textual scholar, who included in his 2000 book Author Unknown a fascinating analysis of the use of language in the work of Moore and of Livingston. His conclusion, built step by step on literary evidence, is that Livingston, and not Moore, authored the poem in question.

But even we lay people, dear reader, can probably deduce this for ourselves by reading further examples of poetry.

For example, contrast with Moore’s grim and foreboding efforts the poem Livingston wrote for his own daughter’s marriage:

‘Twas summer when softly the breezes were blowing And Hudson majestic so sweetly was flowing The groves rang with music & accents of pleasure And nature in rapture beat time to the measure When Helen and Jonas so true and so loving Along the green lawn were seen arm in arm moving Sweet daffodils, violets and roses spontaneous Wherever they wandered sprang up instantaneous.And another, in a letter to his brother, praising the sewing of a cousin:

To my dear brother Beekman I sit down to write Ten minutes past eight & a very cold night. Not far from me sits with a baullancy cap on Our very good couzin, Elizabeth Tappen, A tighter young seamstress you’d ne’er wish to see And she (blessings on her) is sewing for me. New shirts & new cravats this morning cut out Are tumbled in heaps and lye huddled about. My wardrobe (a wonder) will soon be enriched With ruffles new hemmed & wristbands new stitched.The only real benefit from Moore’s perpetrated fraud is that Livingston’s poem has survived for generations to enjoy it. Perhaps now, thanks to Donald Foster, its true author will be recognized.

St. Nicholas Day: Part 1

Today is the Feast of St. Nicholas. On the eve of this day, our children put out their shoes, and in the morning each finds therein a golden walnut (we have quite a collection by now) and one or two small gold-wrapped treats. In honor of this day, I post a tribute to the author of “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” Henry Livingston, Jr.

“Uh, Henry Who?” you are muttering. “I thought it was written by Clement Clarke Moore.” Well, that’s what Clement Clarke Moore would like you to think, too, unless he has repented his wicked ways in whatever hell is the repository of naughty plagiarists.

Henry Livingston (1748-1829) was born in Poughkeepsie, New York. As a young man he served briefly in the army; later he worked as a farmer and surveyor, and in his spare time wrote poetry and made sketches for the amusement of his large family (eventually nine children). His daughter Eliza wrote, “When we were children he used to entertain us on winter evenings by getting down the paint box… first he would portray something very pathetic, which would melt us to tears; the next thing would be so comic, that we would be almost wild with laughter.”

Some of his work was published anonymously in local papers and journals. One of these poems was “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” which the children recalled their father reciting to them in the early 1800s. It made its way through the family’s various households and it was submitted, as usual anonymously, and printed in the newspaper. In this pre-electronic era, writing and reading poetry were popular pastimes, and there was plenty of dreck going around. But this particular poem was well-received, and it grew in popularity. Livingston died a few years later, unacknowledged as its author, except by his family.

Enter Clement Clarke Moore (1779-1863), a prosperous Biblical scholar in New York and a relative of Livingston by marriage. Moore also dabbled in poetry in his spare time, churning out tracts and verses admonishing children and reminding them to be humble and serious. Here is an excerpt from Moore’s jolly poem “Old Santeclaus,” written from Santa’s perspective:

But where I found the children naughty, In manners rude, in temper haughty, Thankless to parents, liars, swearers, Boxers, or cheats, or base tale-bearers, I left a long, black, birchen rod, Such as the dread command of God Directs a Parent’s hand to use When virtue’s path his sons refuse.Or, how about this cheery, romantic poem Moore penned for his daughter on her wedding day:

But oh! how soon we pass this endless track,

That, like perspective art, deludes our view:

And, when we turn and on our path look back,

How short the distance! and our steps how few!

Till death do part, how gaily we repeat

When joy and health are in their prime and strength:

Life is a vista then whose borders meet;

So endless, to our fancy, seems its length.

Trust not the gilded mists and clouds that rise

Where flattering Hope and fickle Fancy reign;

But turn from these, and seek with anxious eyes

The clear bright atmosphere of Truth’s domain.

(continued on December 7th!)

Advent II: Journey to Bethlehem

Holding up all this falling

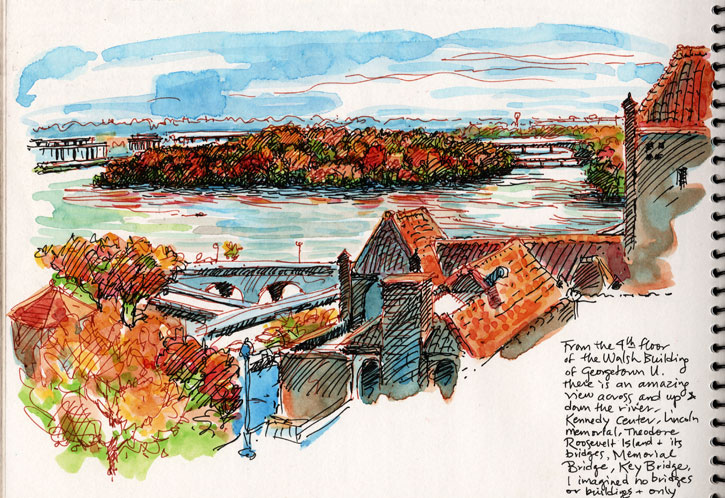

Today is the birthday of Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926), and so I post his poem for late autumn, along with a sketch made from the window of the Georgetown University building where my daughter has her weekly Sunday school class, and where therefore I am fortunate enough to spend a quiet hour thinking, organizing, and gazing upon this view. The setting inevitably drives my thoughts back in time—to Captain John Smith sailing up toward Great Falls… to the Native American village that preceded Georgetown… to the geological forces that carved out this valley… I am SUPPOSED to be planning my week, which seems laughable in context.

The leaves are falling, falling as if from far up,

as if orchards were dying high in space.

Each leaf falls as if it were motioning “no.”

And tonight the heavy earth is falling

away from all other stars in the loneliness.

We’re all falling. This hand here is falling.

And look at the other one. It’s in them all.

And yet there is Someone, whose hands

infinitely calm, holding up all this falling.

—Rainer Maria Rilke

Revelry

Every year, on my to-do list for early October is: Buy Revels Tickets.

If you are not already familiar with these wonderful festivals, well, it’s about time.

The Revels was first created for the New York stage in 1957 by musician, teacher, and author John Langstaff as a celebration of traditional seasonal music, dancing, and storytelling. But it was not simply a stage performance. Langstaff realized that many of us are starved for the connection to the seasons that was part of human beings’ lives for millennia but which for the modern plugged-in citizen has largely disappeared.

Our ancestors didn’t buy tickets to watch a harvest festival, or a planting ritual, or a plea to the gods for the return of sunlight; they MADE every festival, with its traditional songs, dances, foods, and tales, all of which grew naturally out of their lives and acknowledged the continual turning of the year with its growth, loss and rebirth, sorrows and joys.

So Langstaff’s Revels straddles worlds old and new, with professionals and amateurs working together, to create events simultaneously entertaining, educational and participatory, in which audience members watch and listen, laugh (and cry), sing, dance, and sometimes join those on stage to work out a skit or song.

After his initial New York show, and a Hallmark Hall of Fame Christmas Masque (in which a young Dustin Hoffman played a dragon!), Langstaff presented a Revels in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the concept took off. Since then numerous Revels groups have formed around the country, with permanent staff members and lots of eager volunteers, to bring these celebrations to the public, usually one in spring or summer and one near the Winter Solstice.

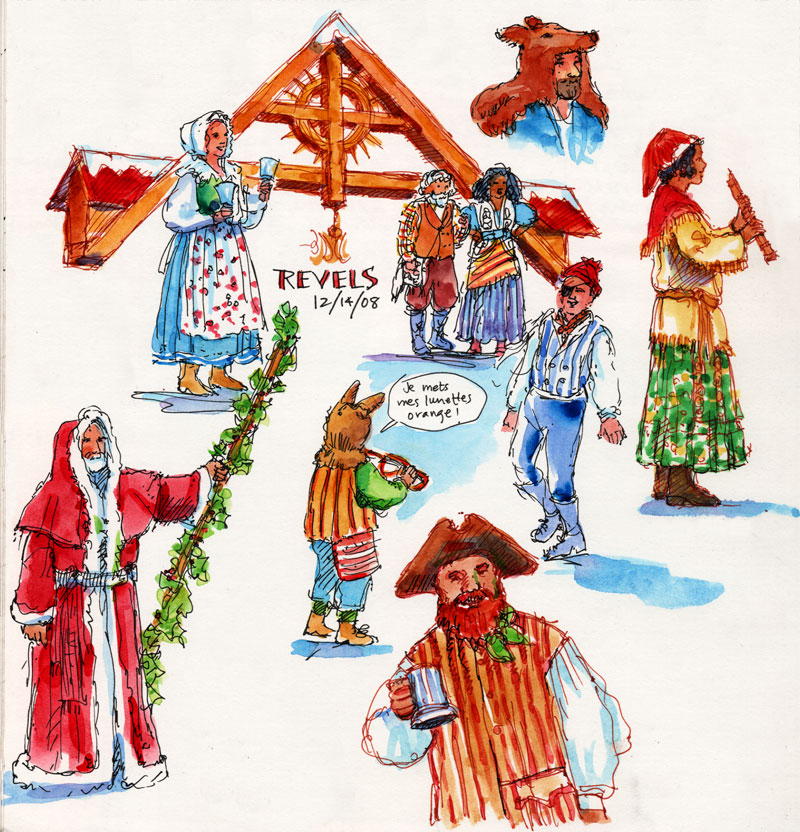

Langstaff’s first Revels incorporated medieval music, but over the years the repertoire has expanded to include traditional seasonal celebrations from all over the world and from many historical periods. Our family has enjoyed the Revels of India, Russia, Scandinavia, French Canada (from which these sketches), Early America, Victorian and medieval England, Renaissance Italy, and the Celtic world, each with appropriately gorgeous, colorful and meticulously researched music, folklore, customs, sets, and costumes.

This year’s DC Revels is set in Thomas Hardy’s rural England. If, in the midst of this season of darkness, you wish to find light—as well as a couple of hours’ joyful immersion in another time and place—then you are in luck. We always go as part of a great big group (then continue our own Revels afterward with dinner and music), but we didn’t buy ALL the tickets. We left some for you.