Throughout the 19th century, Europe remained indisputably the center of the Western art world. By the early 20th century, however, a conjunction of circumstances led to a significant non-European artistic development.

A devastating world war, followed only a decade later by widespread economic depression, the rapid decay and displacement of antique regimes, the alarming ascent of megalomaniacs to power, the ominous signs of another imminent war—all resulted in immense disruption and the repudiation of conventions and belief systems in every facet of society, including the arts, on both sides of the Atlantic. Another result of this disturbance was the arrival on U.S. shores of emigrating European intellectuals, scientists, writers, musicians—and artists.

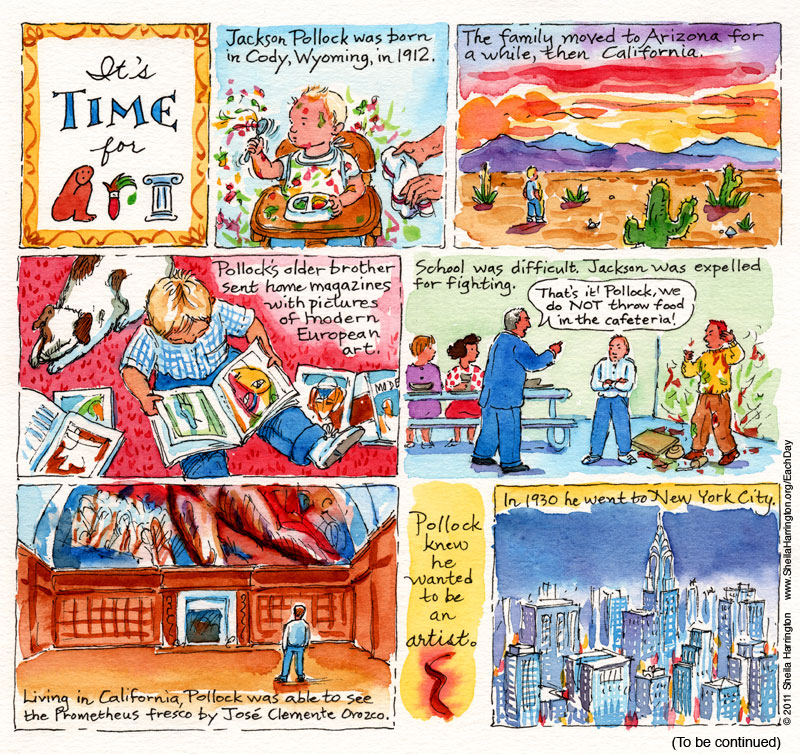

American artists were already actively familiar with what was happening on European easels. Some had spent time studying and working abroad. Others had attempted a departure from Old World movements to pursue more locally relevant directions based on indigenous traditions and subject matter. In the 1930s this was encouraged by WPA funding of new, large-scale public art.

If you like to think of the United States as a giant compost heap (I do), you can see that this blend of rich organic matter and seed varieties would result in some interesting hybrids. Modern American painting experiments reflected diverse influences: the flattening abstraction of Cubism, the fluid intensity of Expressionism, the subconscious/dream imagery of Surrealism, the spontaneity and iconoclasm of Dada, the scale and power of Mexican mural-painting.

But someone came along whose work simultaneously drew upon, melded, and broke the boundaries of all these, with the birth of Abstract Expressionism—a purely materialist expressive form that seems somehow appropriate for the United States, the ultimate “materialist” nation. This was Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), whose birthday it is today. (Please see Action Jackson Part 2.)

For the story of another artist born on this day, please see It’s an Oldenburg.