On this day in 1773 a committee of the Charlestown (South Carolina) Library Society established the first public museum in the United States. Except that there wasn’t yet a United States. South Carolina was still a British colony, and the Charlestown Library Society’s inspiration for its project was the British Museum, the world’s first national public museum, founded in 1753. But by the time the doors of the new museum opened to the public in 1824, South Carolina was, and has mostly remained, part of the U.S.A. To this day you can visit and admire its displays of local natural history specimens, which the [now] Charleston Museum has continued to acquire over the centuries, along with South Carolina memorabilia.

Collecting is undoubtedly a natural human impulse, ever since our hairy ancestors stored up grain for the winter. Once basic necessities were taken care of, human beings with leisure time and/or disposable income continued for millennia to assemble various collections, from seashells to sapphires, but they were primarily for private enjoyment, profit, or study. Royalty and the well-to-do collected, and even commissioned, statuary, paintings, and elaborate furnishings for their palaces. Scholars created and collected manuscripts to share with other scholars. Scientists and amateurs alike collected unusual plants, animals, fossils, and other natural specimens, increasingly so from the 18th century onward as human beings questioned assumptions about the origins of life, the earth and the universe.

But what we now call a Museum did not exist until rather recently. The word comes from the Mouseion at Alexandria, Egypt, which was not a collection of objects for perusal by curious passersby but rather a gathering place for scholars to share scientific and mathematical discoveries (option #2 above). If you were an educated Greek male living in the Mediterranean world in the 3rd century BC and possessed both scholarly interests and travel funds, off you went to Alexandria, which had by then replaced Athens as a cultural center. Euclid studied there. So did Archimedes. The Mouseion included the famous Library of Alexandria, which sought to collect works (or copies thereof) from all over the ancient world, and at its height boasted hundreds of thousands of papyrus scrolls. Eratosthenes served as one of its librarians.

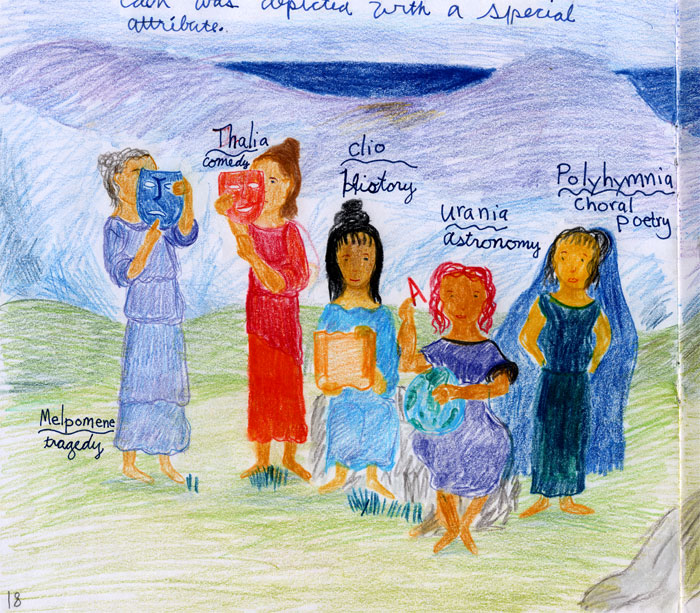

The name Mouseion indicated an institution dedicated to the Muses, who are the nine daughters of Mnemosyne, goddess of memory. Each daughter embodies a different pursuit—Lyric Poetry, Tragedy, History, etc.—and is responsible for its nurture and inspiration. These are offspring to brag about at any parent gathering. “So, what are your daughters up to these days?” “Oh, they’re the Muses of Choral Poetry… Dance… Astronomy… .” References to the Muses abound in painting and literature, from Raphael to Moreau, Homer to Shakespeare.

We honor them still when we speak of Music, or when we cross the threshold of one of the world’s thousands of Museums, which today often still serve as centers for scholarly study, but in addition are open to ordinary citizens like you and me and contain fabulous collections of every imaginable kind of art, artifact, and animal, in every possible subject—science, history, transportation, sports, toys, bananas (I kid you not)—where we can open our eyes and our minds in wonder. And even get a slice of pizza and a postcard. Thank you, oh Muses.

This is a drawing of five of them, from my daughter’s homeschooling Ancient Greece main lesson block.