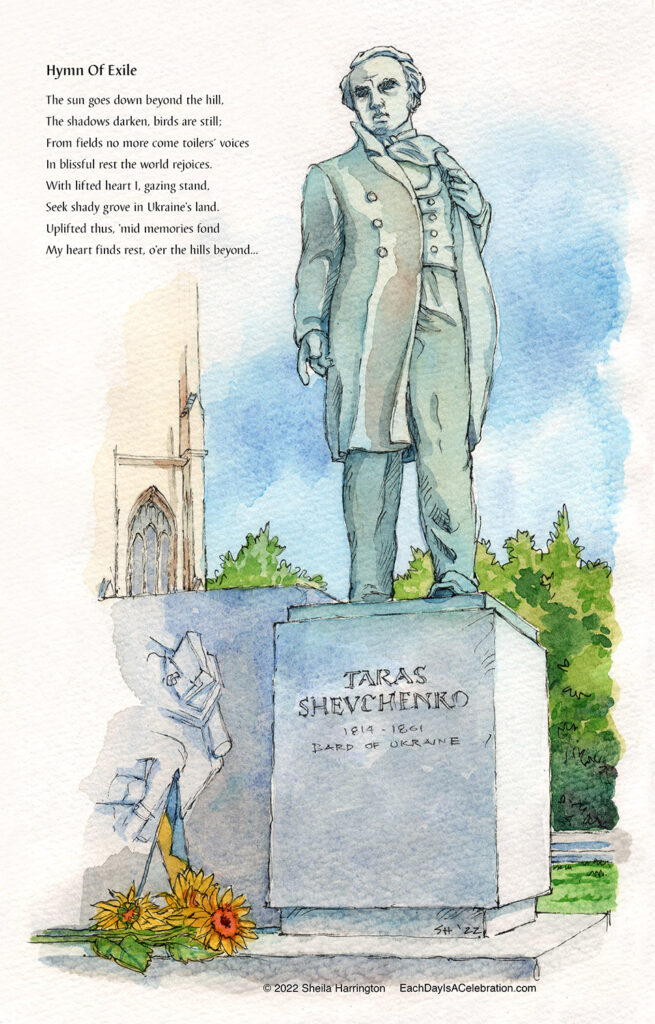

Today is the birthday (at least on the Gregorian calendar) of Ukrainian artist Taras Shevchenko, 1814-1861. If you walk southward on 22nd Street toward P Street in Washington, DC, you will pass a monument to Shevchenko, across from the Church of the Pilgrims. Since the statue is erected on a concrete island in the middle of two-way traffic, to examine it further you can’t just stroll by idly but will need to make it your pedestrian destination.

Taras Shevchenko was born in 1814 in the village of Moryntsi in what is now Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire), into a family of serfs, his father a merchant whom Taras assisted. When he was 11 he was orphaned and spent the next several years working at a variety of jobs for the local cleric, herding sheep, driving a delivery wagon, supplying fire and water for the cleric’s school and simultaneously taking grammar classes and discovering Ukrainian literature. At a young age, Schevchenko displayed gifts not only for language and writing poetry but also for painting and drawing, sketching self-portraits and local figures and landscapes. At 14 he obtained work as a serving boy at the Engelgardt court in Vilshana. At first Shevchenko’s master had him punished for his artistic pursuits; later, he apparently relented, and when the court moved to St. Petersburg and, perhaps for the status implied in having a court artist, sent Shevchenko to study painting. His work increasingly received recognition and won awards. At 24 his freedom from serfdom was obtained by auctioning a portrait.

It was Shevchenko’s poetry, however, that led eventually to his persecution. Having been divided and ruled by multiple empires (Polish-Lithuanian, Ottoman, Russian) for centuries, Ukraine was experiencing by the 19th century a burgeoning nationalist movement. Shevchenko’s own growing nationalism increasingly inspired his work. His art depicted Ukrainian cultural figures and monuments and historical and archeological sites. His writings expressed not only traditions and folklore of the Ukrainian people but also described the conditions under which Ukraine was suffering under foreign rule. Combining intimate lyricism with biting political sarcasm, he aimed to spark the desire for liberty in his fellow Ukrainians. He wrote in Ukrainian (as well as Russian), which since the 17th century had been periodically banned. Shevchenko also joined the clandestine Ukrainian-Slavic Society which promoted national autonomy and a Ukrainian language revival.

Shevchenko was arrested, convicted for “writing in the Ukrainian language, promoting the independence of Ukraine and ridiculing the members of the Russian Imperial House,” exiled to a Russian military garrison, and forbidden to write or paint. Curiously, he was first sent to accompany a naval expedition to document the coastline, after which he was confined for seven difficult years in a remote penal colony. When he was finally released, he was forbidden to return to Ukraine. He spent the next four years of his life writing and painting, but his harsh imprisonment had affected his health and he died in 1861, shortly before the emancipation of the serfs.

In his importance to Ukrainian culture, Shevchenko has been compared by historians at the Library of Congress to Walt Whitman in the USA and Rainer Maria Rilke in Germany; yet neither was also a painter, illustrator, and political revolutionary. As Ukraine struggles courageously to maintain its freedom as a sovereign nation in the face of an invasion led by a ruthless and possibly psychopathic neighbor, Shevchenko’s own history is inspirational. You can learn more about him, his poetry, and his paintings on the Shevchenko Museum website.

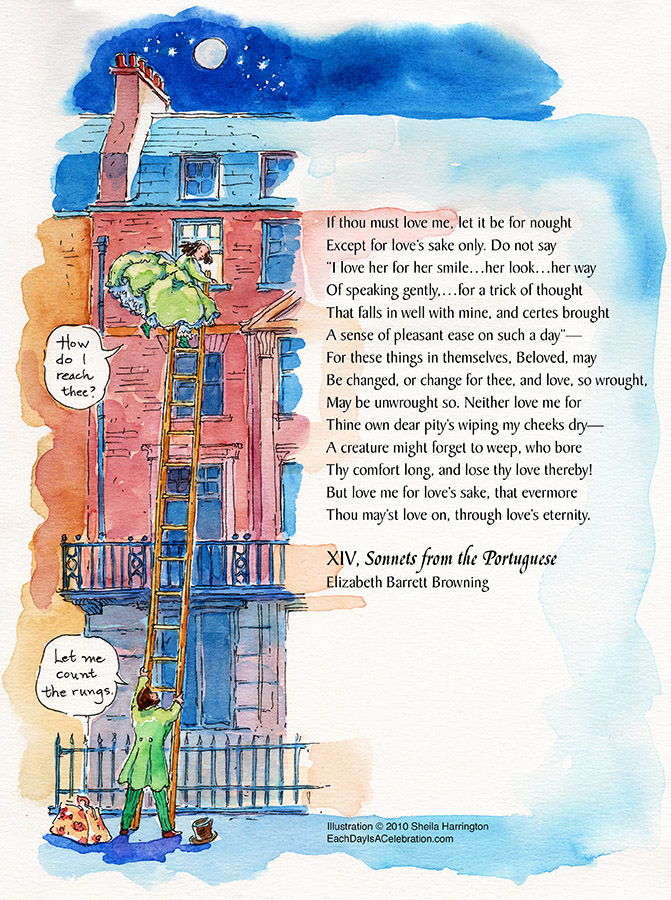

Hymn Of Exile

The sun goes down beyond the hill,

The shadows darken, birds are still;

From fields no more come toilers’ voices

In blissful rest the world rejoices.

With lifted heart I, gazing stand,

Seek shady grove in Ukraine’s land.

Uplifted thus, ‘mid memories fond

My heart finds rest, o’er the hills beyond.

On fields and woods the darkness falls

From heaven blue a bright star calls,

The tears fall down. Oh, evening star!

Hast thou appeared in Ukraine far?

In that fair land do sweet eyes seek thee

Dear eyes that once were wont to greet me?

Have eyes forgotten their tryst to keep?

Oh then, in slumber let them sleep

No longer o’er my fate to weep.

1847, Orsk Fortress, translated by A. J. Hunter