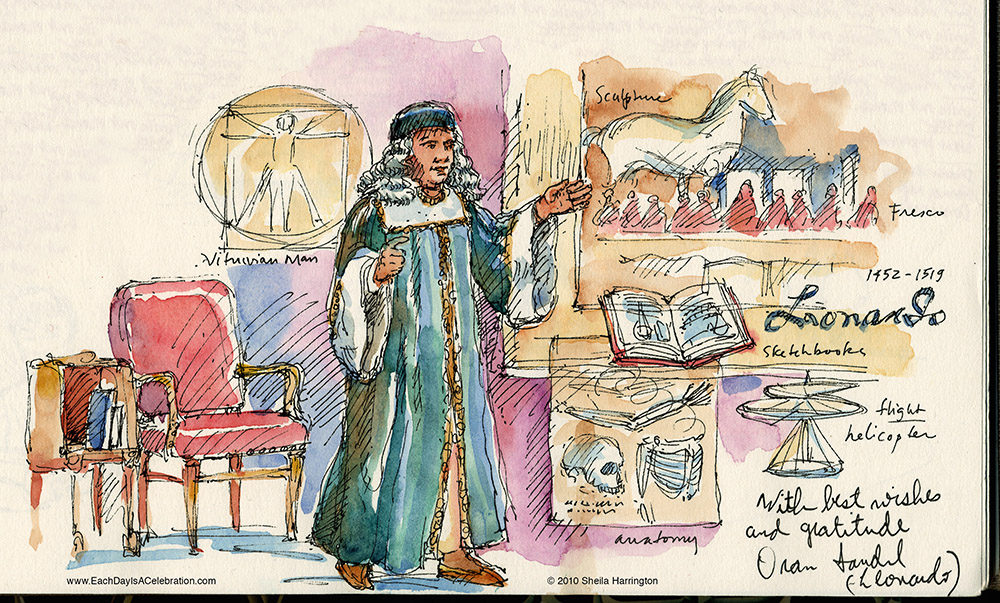

In the middle of Italy, in the middle of the 15th century, a prosperous Florentine attorney had an assignation with a peasant girl who subsequently became pregnant. Having no intention of marrying out of his class, he nevertheless adopted the child (and married someone else). But it’s doubtful either suspected that their dalliance would produce one of the most extraordinary geniuses of an extraordinary era. Or perhaps of any era. Today is the birthday of that baby, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), and what can I say of this man that hasn’t already been said a thousand times, and much better too? But in respect I devote today’s post to him, along with a sketch I made at a Smithsonian Discovery Theater performance about his life (signed by the actor, Oran Sandel).

The period we call the Italian Renaissance stretched from the 14th to the 16th centuries, when the disposable wealth of a growing middle class helped to fund travel, trade, manufacture, learning and art, and the educated citizen reached back beyond a medieval sleep to rediscover the classical world and open his mind to earth and sky. Leonardo’s life-span fell at the heart of this era. He was not an isolated pheomenon; he was part of a continuum that stretched from Piero della Francesca and Donatello to Michelangelo and Raphael. And yet within this continuum he is remarkable.

Little Leonardo had no formal schooling, but apparently showed an early aptitude for mathematics, music, and drawing, and at fourteen was apprenticed to the artist Andrea del Verocchio. Now, “artist” is a label with a shifting interpretation, and in 15th-century Italy it did not mean a superstar who sat pouring out his heart and his genius before an easel or a block of marble. No, an artist was a bloke whom you hired to manage all sorts of practical and decorative tasks. Verrochio got his start as a goldsmith, and when his work sent him to Rome and he perceived the city’s appreciation of statuary, he said to himself, “Allora—I can do that!” And so he did, creating sculpture in plaster, marble, and bronze, with the occasional bell-casting to keep pasta on the table.

Leonardo was a gifted pupil who studied both artistic and technical skills, working in metal, plaster, leather, and wood as well as paint, and, the story goes, he quickly surpassed his master. At 20 he was admitted to a guild composed of artists, chemists, and physicians (perhaps this made it handy to study anatomy).

He began to receive commissions, and after a few years applied to the Duke of Milan for an appointment, writing that he could design bridges, canals, and buildings; make light and heavy weaponry; create sculpture; and paint. How’s that for a resume? He was hired, and his many tasks included not only those above but decorating palace rooms, creating pageants, and designing costumes for festivals. It seems like a waste of his talents, but one of the most striking and curious aspects of Leonardo was his apparently inexhaustible interest in everything and its effect on his limitless imagination.

The list of his interests is stunning. Of course he was interested in the human face and form in all its positions, moods, and stages of life, from the beautiful to the grotesque, from the skeleton to the fetus to the movement of blood. But he also loved animal life, and all of nature, not just its forms but its structures and functions. He was fascinated by the movement of water, by clouds, by astronomy. He explored the wonders of geometry, optics, color, light, heat, sound, magnetism, geology, fossils, the chemistry of pigments, the flight of birds. He filled thousands and thousands of journal pages with his observations and sketches. He designed (famously ahead of his time) predecessors of the armored tank, the helicopter, the hang-glider.

And, yes, he painted. Probably, although we are aware of his multi-faceted pursuits, we remember him best for his painting. The Mona Lisa. The Last Supper. The Virgin of the Rocks. He didn’t leave us many (and what he did leave is astonishing)—a mere handful of finished paintings and sculptures. Thousands of sketches. And a number of works that are unfinished, or deteriorating because of his use of experimental materials. When we gaze upon his people, living and breathing and thinking and feeling upon the canvas, we might wonder:

What was going on with this artist that he didn’t feel compelled to bring forth a few more amazing works of art?

Was he such a perfectionist that the energy for his approach was limited? (He was famous for—and exasperated his clients with—the preparation, the thought, the hundreds of studies that preceded any final work.)

Was the process more interesting to him than the product?

What’s with all the hobbies? Did he think he was going to live FOREVER, for heaven’s sake?

Near the end of his life, when he was working for the French king François I (designing canals, arranging pageants), he wrote despairingly in one of his notebooks, “I have wasted my hours.” But in another he wrote, “As a day well-spent makes it sweet to sleep, so a life well-spent makes it sweet to die.” I am hoping it is the latter thought that was with him at the end.