Today is the birthday of writer Shirley Jackson (1916-1965), born in San Francisco, California, but transplanted to the East Coast where she attended university and eventually settled with her husband in Vermont, raising a large family but all the while continuing, somehow, between PTA meetings and making hamburger casseroles, to write.

Many readers have probably been introduced to Jackson through her short story, “The Lottery,” once a classic of the high school English syllabus, which when it was published in the New Yorker in 1948 evoked overwhelming response exceeding that of any previously published New Yorker story.

Jackson came to my attention, however, through the books my parents owned: her collections of dark, evocative, seemingly plotless short stories that are typical to this day of New Yorker fiction (probably a contemporary literary parallel of Abstract Expressionism that nevertheless persists into the 21st century); and her similarly eerie, compelling novels. As a child, I was fascinated yet rather baffled by Jackson’s fiction.

What I really liked, however, were her memoirs of her children, Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons, which I read and re-read, the pages yellowing and held together with Scotch tape. Her unsentimental, low-key, definitely politically incorrect descriptions of ordinary daily life with her four bright, imaginative children, her hovering-on-the-fringes professor husband, and their cats and dogs, in their book-stuffed rural Vermont farmhouse, made me laugh again and again. When I grew up I read the books to my husband and offspring, and now they read them to one another. Into our common family vocabulary have effortlessly crept quotes from the various children (see title above).

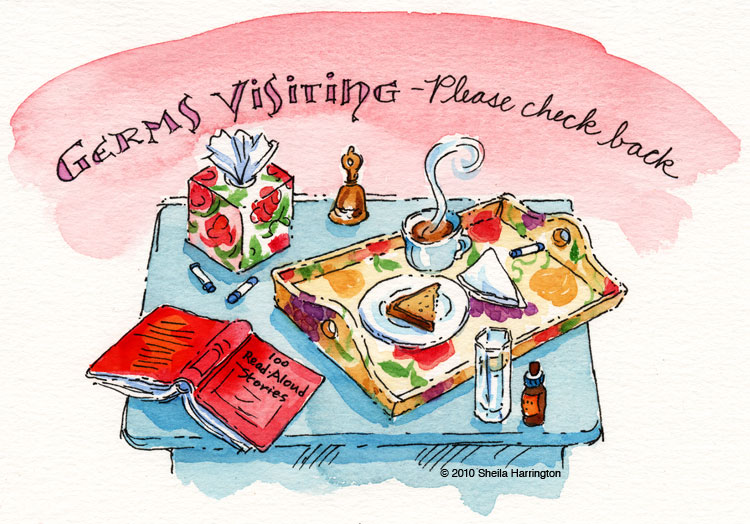

This winter, when you and your family are all abed with the flu, read aloud the chapter, “The Night We All Had Grippe.” Laughter is healing. Happy birthday, Shirley Jackson, many happy cookies, and thank you ever so for the years of healing episodes.