A sketching expedition with my daughter last spring.

Tag: Spring

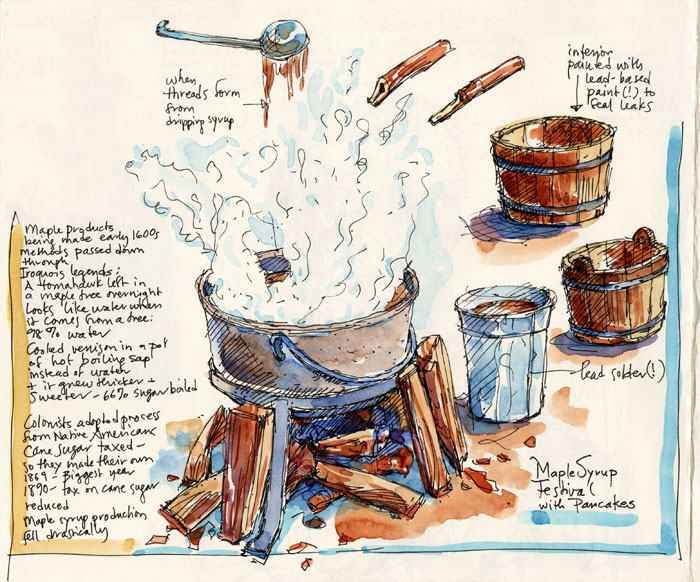

Sugaring off

Spring is a time for field trips—outdoors, if possible. This is from my sketchbook, when, as part of a homeschooling Farming block one year, we visited Cunningham Falls in the Catoctin Mountains for their annual maple syrup festival. We were able to see the entire process from tree-tapping to boiling down sap to sampling the final product at a pancake breakfast. Wonderful park guides provided explanations of each step and answered our many questions. The syrup was a whole lot better than their Lake Wobegon pancakes, though. They definitely need a new recipe.

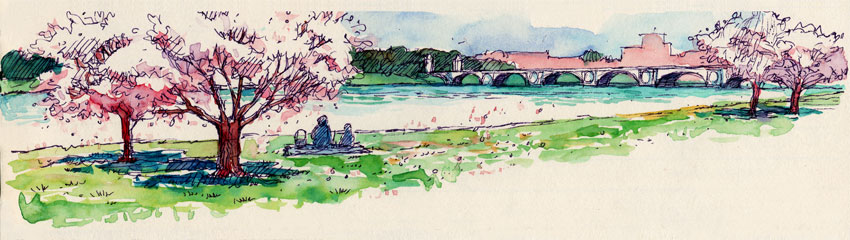

Cherry Blossom Breakfast

This morning we officially began our homeschooling Botany block, with springtime poetry, an early morning picnic and stroll under the cherry blossoms, and a long conversation about the astonishing, exuberant and generous world of plants, which brings forth hourly surprises in this season. (Was it only last month that a mountain of snow still blocked the alley exit?)

Lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone;

the flowers appear on the earth;

the time of the singing of birds is come,

and the voice of the turtle is heard in our land.

The fig tree putteth forth her green figs,

and the vines with the tender grape give a good smell.

Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

—Song of Solomon 2:11-13

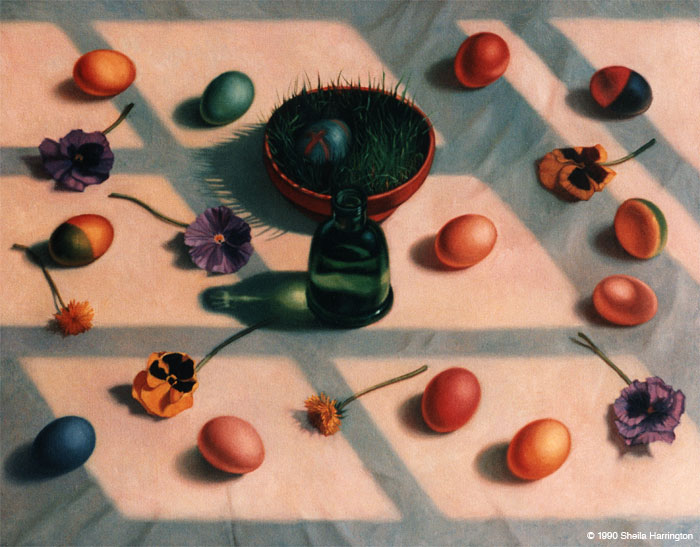

Easter Garden

Some years ago I was moved to paint a still life based on our Easter customs.

Every year during Lent we plant a tiny garden of rye or clover seed and set it in the middle of the dining room table. And every year it’s startling (even though I’ve seen it so often before!) to find one morning that new, fragile green sprouts have pushed their way upward through the weight of earth. What fortitude. What will to live. So may we all find our way toward the light this springtime season.

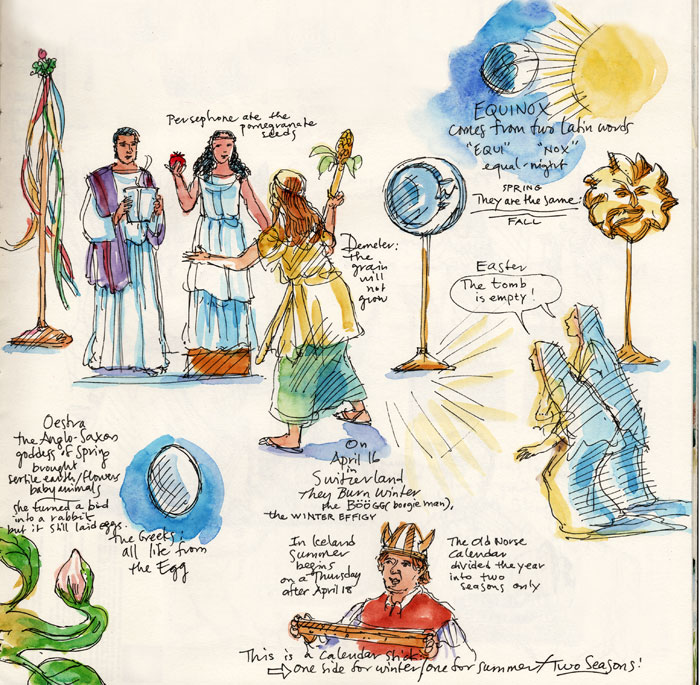

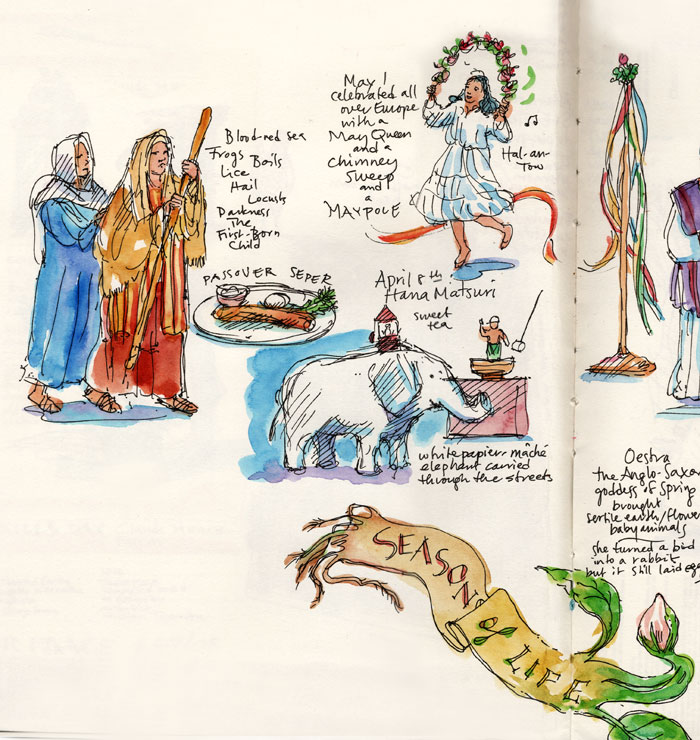

Season of Life 2

Season of Life 1

Each year Discovery Theater at the Smithsonian offers a performance in celebration of spring festivals in various cultures. My daughter and I attended as part of a homeschoolers’ outing, and I took along my sketchbook. The homages to the season were skillfully woven together with music, dancing, brief dramatic episodes, and rapid costume and prop changes by the very small yet impressive multi-talented cast. It was lively and engaging, but really tough to sketch and make notes! More like a series of scrawls. Since these fill a spread of my sketchbook, it’s too big for one post, so just the left side today: Passover, the Maypole, and Hana Matsuri.

C&O Canal

From my sketchbook, in the spring a couple of years ago. We took a break from lessons in the middle of the week to walk along the C&O Canal, look at emerging wildflowers, visit the small history exhibit in the Great Falls Tavern Visitors Center, and have a picnic lunch in its garden. One of the many advantages of homeschooling.

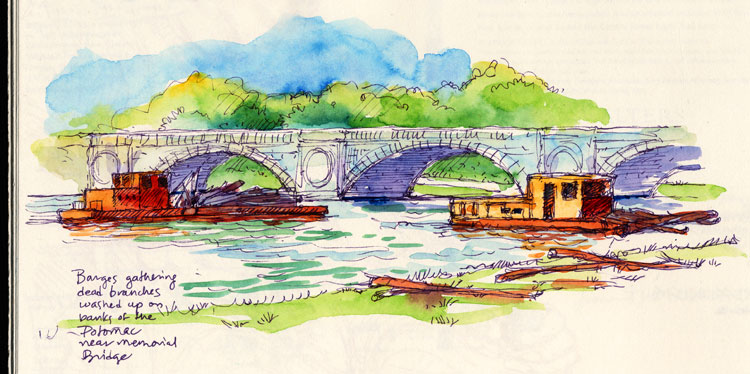

Spring Cleaning

I’m sorry; it’s not what you hoped—that is, if you were hoping for tips on getting your life and your environment organized. (Actually I came across a really useful blog for that the other day, though; Totally Together Journal.) No, this is the City of Washington, DC doing its river-tidying, which my daughter and I discovered by accident. Did you ever wonder what happens to the logs and branches that tumble into the Potomac River upstream whenever there is a hearty spring rainstorm? Well, a tugboat glides up and down the river gathering them in its little metal arms and transfers them to a barge for removal. So they don’t bash into you when you are out in your Thompson’s or Fletcher’s rental canoe. Your DC taxes at work.

Loveliest of Trees

Every year about now I start muttering this poem to myself. And I ponder how suitable it was that its author, Alfred Edward Housman (1859-1936), was born on this day, in the season of the lovely, evanescent, and melancholy cherry blossom.

Housman was one of seven children of a rather depressed solicitor in Fockburg, England who had a tendency to invest heavily in failed inventions. No wonder he was depressed. Housman’s health was frail, and in school he was subject to bullying. As many were, in pretty much any fine olde boys’ public school. His beloved mother’s death when he was twelve was a severe blow. However, as a student he showed great promise, and he won a scholarship to Oxford, where he took up classics.

Although he was brilliant, Housman was unwilling to expend much energy on what didn’t interest him, and he much preferred his studies of the Latin poets to philosophy and ancient history. He failed to pass his final exams, and there is speculation that the cause was not only neglect of his studies but also the disappointing (and lifelong) attachment he had developed to his school roommate, Moses Jackson, which never went beyond friendship (Jackson being heterosexual).

Housman’s failure to pass his studies made it impossible to enter a position in academia, but Jackson, who couldn’t give him True Love, obtained for Housman through his connections the next best thing—a Steady Government Job. (And that sounds really attractive in the current economy.) So for the next ten years Housman was a London Patent Office Clerk by day and classical scholar by night, studying Greek and Roman classics independently and writing articles for learned journals, gradually gaining an impressive reputation that led to a professorship in Latin, first at University College, London, and then Cambridge University, where he eventually published several volumes of his meticulous textual analysis and translation.

But do we remember Housman for his brilliant Latin scholarship? No, we do not. Unless we are brilliant Latin scholars ourselves. No, this clerk by day and scholar by night was somehow finding the time to write evocative lyrical poetry. In 1896 he assembled a collection of 63 of his poems and went looking for a publisher. After being rejected by several, he decided to publish the collection, titled A Shropshire Lad, at his own expense, surprising his colleagues, who evidently had had no idea of Housman’s other interest. The book sold slowly at first, but as musicians set some of his ballad-like poems to music, its reputation grew, and with the advent of the First World War, his themes of death and loss struck a chord in the public. It became one of the most popular volumes of serious poetry ever published.

Apparently an aloof, intimidating professor with a sarcastic wit, Housman was not an easy companion, and when Jackson married, he did not even send Housman word. Housman gradually became increasingly reclusive. But when Jackson was gravely ill in Canada, Housman decided to assemble his unpublished poems so that his old friend could read them before he died. These were published as Last Poems in 1922, 36 years after A Shropshire Lad. One more collection was published posthumously.

And that’s it. What Housman created as a sideline (“I am not a poet by trade; I am a professor of Latin”) has become an inextricable and unforgettable component of the body of English poetry. Housman said once, “The emotional part of my life was over when I was thirty-five years old.” Yet his poetry, at once spare and vivid, is imbued with feeling, without being sentimental. What he did not permit himself in life he has given us on the page.

So go for a walk under the pink and drifting petals, and wish Alfred Housman a Happy Birthday.