Category: Illustration

Library of Congress-Part 1

On this day in 1800, President John Adams approved legislation appropriating $5,000 to fund a hitherto nonexistent Congressional library.

Now, when the United States was young and the ink was still drying on the [mostly] ratified Constitution, its first Congress met for a short while (1790 to 1800) in Philadelphia. This contender for the role of Nation’s Capital was merely a disappointed temporary location, resigned to the government’s eventual transfer south. In the meantime, however, Philadelphia was, thanks largely to William Penn and Benjamin Franklin, a highly livable city—the most populated in the country (Washington, DC wasn’t even in the Top Twenty), with paved and lighted streets lined with sidewalks, fine masonry buildings, a university, a hospital, a fire department, gardens and parks, theaters and shops and philosophical societies and libraries—much like today, but without WiFi. The Library Company of Philadelphia offered the use of its fine collection to members of Congress free of charge, at a time when library use was by paid subscription.

When the government packed up and trudged southward to the Potomac in 1800, they said to one another in despair, “Where in this muddy village of farms, taverns, and unfinished government buildings will we do the research and study necessary for Congressional legislation and malediction?”

Fortunately, the previous Congress had been planning ahead, and in 1801, a collection of 740 books and three maps, purchased with the appropriated funds, arrived from London. They were stored, along with the papers Congress had brought from Philadelphia, in a room of the partially-built Capitol Building. It was primarily a collection of legal, economic, and historical works. The next President, Thomas Jefferson (He Who Must Not Be Named in Texas), a voracious scholar himself—if there was any subject that never interested him it is apparently unrecorded—signed a law creating the post of Librarian of Congress.

Fire is a perpetual threat to the flammable cities of civilization, and disaster can result merely from an unsnuffed candle. The Library has suffered from several, mostly minor, fires. But in August 1814, during the War of 1812, the British set about destroying Washington’s public buildings, to avenge the Americans’ destruction of the public buildings of Toronto. Although parts of the Capitol held up remarkably well, its interior, filled with wooden furniture, paintings, and irreplaceable documents and books, was highly flammable. That was the end of the library.

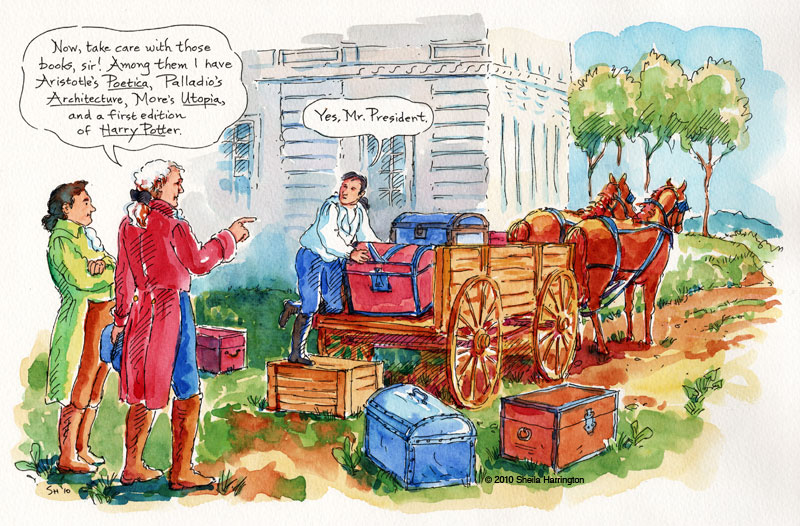

But only temporarily. Because Jefferson, now in retirement and short of cash, offered to sell his personal library to the U.S. government as the foundation of a new collection. So in 1815 he was paid $23,900 for his 6,487 books, which arrived by horse and wagon from Monticello.

What a collection it was. Not only works of law, economics, and history, to replace the lost books. But also: Biography. Geography. Chemistry. Botany. Medicine. Anatomy. Architecture. Philosophy. Painting and sculpture. Theater. Music. Literature. Essays. Mythology. Religion (including a copy of the Koran). And not only in English, but also works in French, Spanish, German, Latin, Greek, and Russian, several of which languages Jefferson spoke or read.

Some members of Congress objected to the collection’s breadth, explaining rather myopically, “the library was too large for the wants of Congress,” but Jefferson famously responded, “There is…no subject to which a member of Congress may not have occasion to refer,” and that statement has guided the Library in its acquisitions over the years.

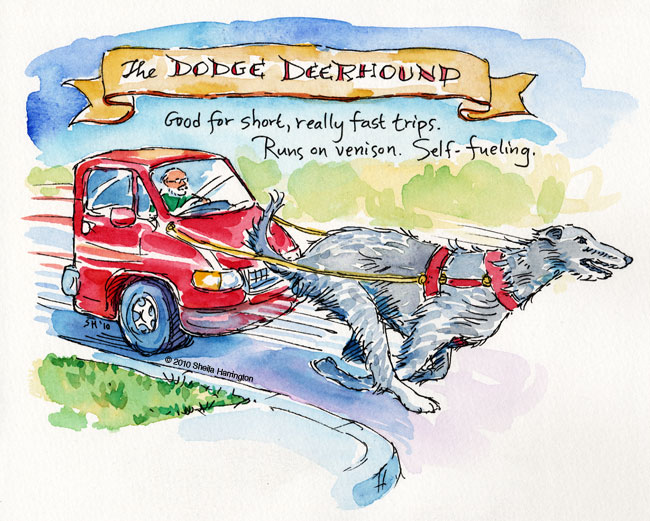

Energy-Efficient Vehicle #1

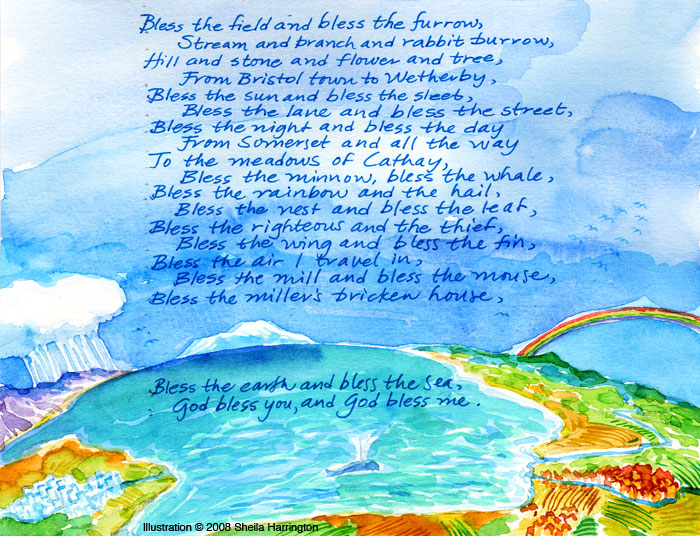

Bless the Field and Bless the Furrow

To begin the work week, a traditional blessing from our homemade family mealtime verse book.

I especially like “Bless the righteous and the thief.” To hold this vision of the world deeply in one’s heart is worth striving for. Ongoing struggle though it may be from day to day. Well, it is for me, anyway.

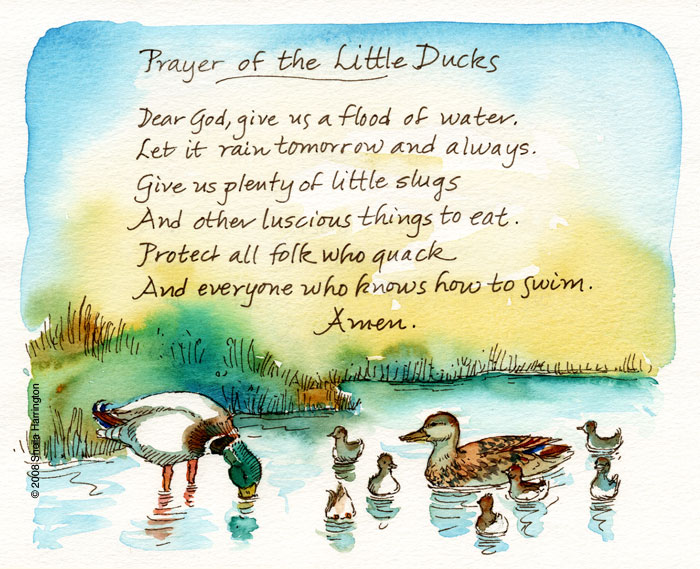

Prayer of the Little Ducks

Mother of Level Measurements

If you were an American housewife setting out to bake a cake or a loaf of bread in the 19th century—or the 18th—or the 17th—you generally relied upon what you had learned at your mother’s side. You assembled flour and milk and sugar and milk and shortening and eggs, estimating amounts as best you could and combining them from memory in the proper order. In 1303 Edward I of England had standardized the pound, and the American colonists brought with them, and still use today, the old English standards of measurement (the British have revised their system several times since then, so we no longer match), and most farm wives could measure in pounds, pecks, and bushels. But as for smaller units you were on your own with vague descriptions (“a dab of cream” “a piece of butter as large as an egg”) or whatever teacups you were fortunate enough to possess.

That is, until Fannie Farmer (1857-1915), who was born on this day in Medford, Massachusetts. Her father was an editor and printer, and her parents believed in higher education for girls, but Fannie suffered a stroke at age 16 (!), which prevented her attending college. What she could do, however, was take up responsibility for the household’s cooking. Evidently she had a natural talent. When the family home became a boarding house, it gained a reputation for its fine meals.

So Farmer was encouraged by a friend to obtain teacher training at the Boston Cooking School, which took a scientific approach to food preparation, and she did so well that she stayed on to become Assistant Principal and then Principal in 1891. And in 1896, Farmer published The Boston Cooking-School Cookbook.

Now, cookbooks were not unknown to American housewives. Amelia Simmons’ American Cookery had been self-published in 1796, with colonial favorites like pumpkin pudding, watermelon pickles, and spruce beer (Mmmm!), and by the late 19th century there was an explosion of cookbooks by women, offering medical mixtures (“A wash to prevent the hair from falling off”) and household advice (“Words of Comfort for a Discouraged Housekeeper”—now there’s one we could use) as well as recipes.

Farmer’s cookbook was even more comprehensive, including sections on the chemistry of cooking and cooking techniques, the specific components of food and why each was necessary for health, how a stove works, how flour is milled, what happens during fermentation, and extensive detailed advice on caring for the sick. In addition to these she offered recipes with straightforward, precise directions and—Ta-Daaa!—Actual Measurements, the tools for which (the standard measuring cup, divided into ounces, and graduated measuring spoons) she had created earlier. The publisher, Little, Brown, had “little” faith in the book’s success, and insisted Farmer foot the printing bill herself. When the book became hugely popular (it has sold millions of copies and has never been out of print), this turned out very well for her because she had retained copyright. Ha! Unlike poor Irma Rombauer who unfortunately sold her rights for $3,000 to Joy of Cooking’s publisher.

Farmer’s success enabled her to open her own cooking school. She wrote other books, one of them focusing on cooking for the invalid; was invited to lecture at Harvard Medical School (which lectures were widely printed and read); wrote a regular cooking column in the Woman’s Home Companion; and continued to test and invent recipes and to lecture until the last few days of her life.

You can find Fannie Farmer’s cookbook today—in its 13th edition—at your local library and bookstore. And to celebrate the birthday of the “Mother of Level Measurements,” as she was called, you can make Fannie Farmer’s “Birthday Cake.” If you own a measuring cup and spoons, that is. I have the recipe right here, and if you email me, I will send it to you. (It may be straightforward by 19th century standards but it’s waaay too long to include here.)

A Dream of Spring

Faith and Begorrah

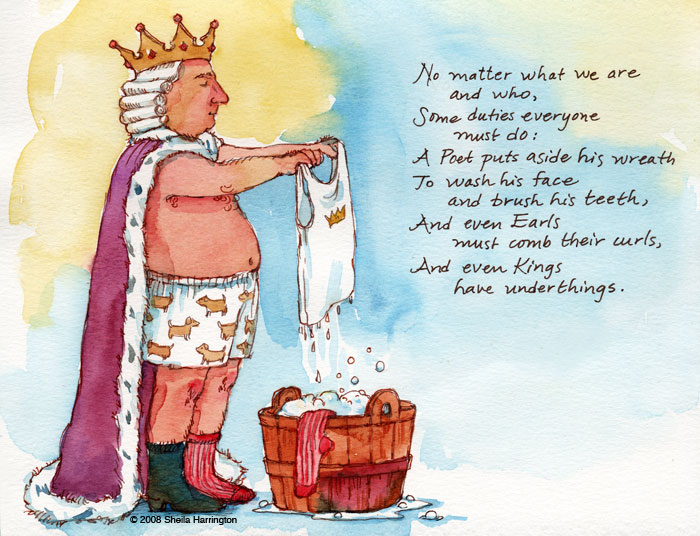

Saturday Chores

This poem, which I believe is by Arthur Guiterman (someone please correct me if I am wrong), is in our family verse book, and sometimes we recite it on a Saturday morning to jump-start the chores. Better, though, is when we play “Happy Little Working Song” from the film Enchanted at a really loud volume. That gets us moving, and into a jolly mood, too.