Philly: Part 4 of 4.

Tag: Library

Let Those People Go

Perhaps you did not hear, one grim day this past summer, about the abrupt dismissal of Hillary Fennell, our library’s much-loved children’s librarian for over 30 years, as part of the sudden and arbitrary termination of all DC Public Library part-time staff throughout the city. So long, folks, there’s the door! Hope you didn’t leave your lunch bag back at your desk, because you won’t see that again! I tried to imagine what logical thought process culminated in this bizarre event.

Cleveland Park Day

If you wander today along Connecticut Avenue between Macomb and Porter Streets between 1 and 5 pm, you will encounter neighbors, local merchants, and folks from the elementary school, library, fire department, and other neighborhood organizations celebrating what’s interesting and fun about Cleveland Park. Attractions include music, food, clowns, a moon bounce, McGruff the Crime Dog, and President and Mrs. Grover Cleveland, long-ago residents presumably returning to check out old stomping grounds and new restaurants.

Among the events will be a tribute to Cleveland Park Library staff whose positions were suddenly and gracelessly slashed over the summer, especially beloved children’s librarian Hillary Fennell, a living encyclopedia of children’s literature and a lovely lady besides, who had served the library and its community for over thirty years. What is story hour without Ms. Hillary? (More on this in the October 5th post.)

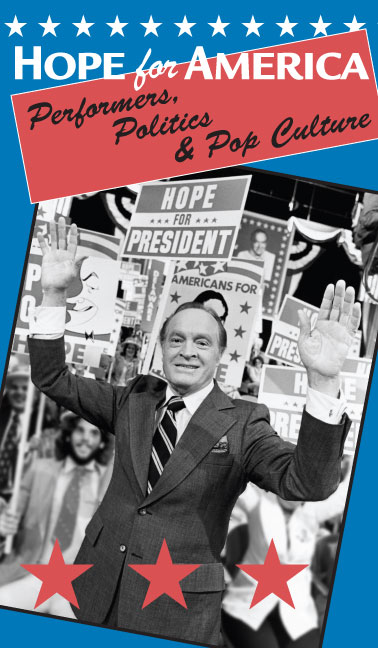

Hope for America

I’ll bet you thought I was about to announce an alternative to fossil fuels, or at least an exciting new political candidate.

No, tonight is the opening reception for a new exhibition in the Bob Hope Gallery at the Library of Congress on which my husband has been working for the past several months. It’s one of many history exhibitions he’s created for the LOC over the years. Hope for America: Performers, Politics & Pop Culture explores the involvement of entertainers in politics throughout the 20th century, often through satirical commentary, sometimes through direct participation. There is also a moving segment on Hope’s work for the USO entertaining troops all over the world, which he did for SEVENTY YEARS. The exhibition features film and television clips and radio broadcasts as well as photos, letters, sheet music, and other artifacts to tell the story.

If you are in the DC area, come visit! I’ll bet you could use a few belly laughs. (This is the cover of the brochure I designed for the exhibit.)

Library of Congress-Part 3

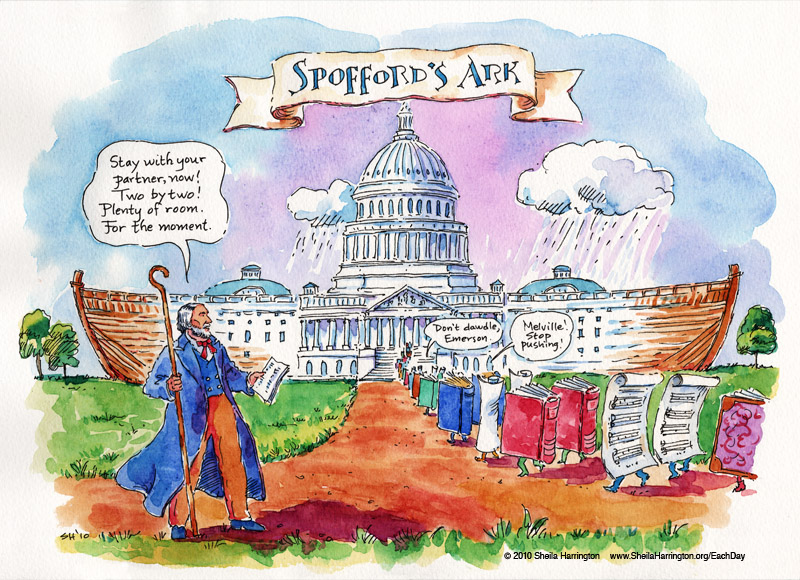

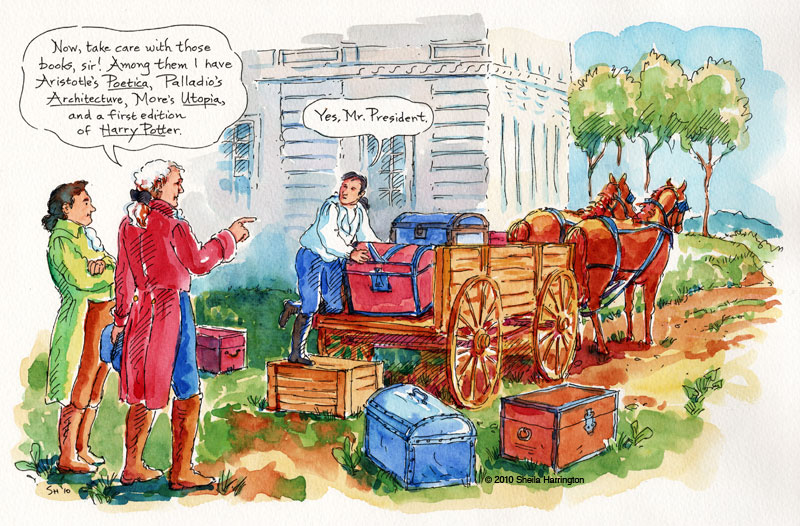

(If this picture is baffling, please see the news story on the Texas school board’s decision to eliminate Thomas Jefferson from its textbooks.)

Continued from Library of Congress–Part 2, May 7th

Spofford proposed a separate building for a library that would equal (or surpass! he suggested temptingly to Congress) the great libraries of Europe. It took about 15 years to hold a design competition and authorize funds, but at last, between 1886 and 1897, an astonishing team of architects, engineers, artists, and craftspeople created the Thomas Jefferson Building, probably the most magnificent structure in Washington, DC, and certainly the most labor-intensive per square inch.

The award-winning design was a building in the style of the Italian Renaissance, “efficient, beautiful, and safe,” and its thoughtful embellishment and finishing—despite a hovering Congress with its eye on the budget—is a suitable tribute to that period of cultural flowering. Stroll through and marvel at the multi-layered ornamentation, in paint, marble, and mosaic, depicting images and figures historical and mythological honoring the higher achievements of humanity: philosophy, natural science, music, art, theology, astronomy, law.

And these many wonders house a collection even more wondrous. Who could have foreseen, on that day in 1800 when John Adams signed the appropriations bill, what would develop from an initial purchase of 740 books and three maps? This is from the Library’s own website:

The Library of Congress is the largest library in the world, with nearly 145 million items on approximately 745 miles of bookshelves. The collections include more than 33 million books and other print materials, 3 million recordings, 12.5 million photographs, 5.3 million maps, 6 million pieces of sheet music and 63 million manuscripts… The Library receives some 22,000 items each working day and adds approximately 10,000 items to the collections daily… In 1992 it acquired its 100 millionth item.

Not only that, but at the Library you will find:

Works in 470 languages. Four Hundred and Seventy.

Newspapers in many of those languages, from all over the world.

Over 5,000 books printed BEFORE 1500, including a Gutenberg Bible.

Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, with Talking Books and other resources available free of charge.

The Center for the Book, created to promote literacy and reading, with affiliates in all 50 states.

The American Folklife Center, with 4,000 collections of stories, music, and oral history.

An ongoing program of lectures, symposia, exhibitions, concerts, book-signings, films, and tours both general and specific.

The Library of Congress also sponsors the popular annual National Book Festival on the Mall, bringing authors and readers together for readings and discussion.

Whew! And that’s not even all….for the rest of it you must go to the website to discover. Or to the Library itself.

The Library of Congress remains a work in progress, an almost unimaginable organizational, classification, conservation and retrieval challenge. Its evolution from modest beginnings is astounding. It has survived fires, civil and world wars, recessions and depressions, and an international information explosion.

And you, dear Reader, should you manage to make it to Washington, DC, and if you are at least 16 years of age (high school students must show that they have first exhausted their other sources for research) and have a valid identification card, such as a driver’s license: YOU are eligible for a Library of Congress Reader Identification card, and you may pursue your studies, with access to hundreds of years of accumulated knowledge and beauty, in the splendid Reading Room of this marvelous, this amazing, this thank-your-lucky-stars national treasure.

Library of Congress-Part 2

Continued from Library of Congress–Part 1, on April 24th

In its two-plus centuries, the Library of Congress has had a mere thirteen Librarians. They often serve a very long time, a sort of Library Supreme Court Justice. One of them was Archibald MacLeish (1892-1982), whose birthday it is today.

Born in Illinois, educated at Yale with a major in English, and at Harvard Law School, MacLeish might have had a straightforward uneventful law career, with writing and teaching as secondary pursuits, but for having served in the Army in World War I. Perhaps it was this wartime-planted seed that was sprouting when he left his law firm after three years and moved to Paris with his wife. There he spent five years writing poetry and drama and hanging out with the Hemingway-Fitzgerald-Pound crowd.

Well, how do you keep ’em down on the firm, after they’ve seen Paree. Instead of resuming his law practice after returning stateside, MacLeish continued to write, and to work for Fortune magazine. He had been, after all, an English major, and some of them do find employment—look at Garrison Keillor.

The anti-fascist viewpoint expressed in MacLeish’s writing drew the attention of President Roosevelt, who decided to appoint MacLeish as the next Librarian of Congress, over Republican Congressional opposition (“Expatriate!” “Communist!” “Poet!”). Professional librarians weren’t too happy about it either, since MacLeish was a Library World illegal immigrant. Once installed, however, he proved his skills and dedication, beginning with a major administrative reorganization of the rather uneven and semi-catalogued Library, clarifying its collection goals (Where are the holes to be filled?) and acquisitions policies (How can we fill them?), and requesting (and receiving!) a major expansion of Library budget and staff.

MacLeish also brought writers onto Library staff, launched poetry readings, wrote speeches for FDR, and much more which you can read about in detail on the Library’s website. Pretty amazing that he could accomplish all this in his 1939 to 1944 term, move on to serve as Assistant Secretary of State, then follow up with a writing/teaching career, winning Pulitzer Prizes for his drama and poetry, for which he is probably better-known.

The current Librarian, Dr. James Billington, has been a serious advocate of the National Digital Library Program, an ongoing project to digitize resources within the Library of Congress, making them accessible to that part of the world’s population (i.e., nearly everyone) which cannot make a personal visit to the physical Library in Washington, DC. In conjunction with this he proposed the creation of a multilingual World Digital Library, which was launched, with UNESCO, in 2009. Billington is a writer and a Russian scholar with a list of talents, awards, and accomplishments inside and outside the Library that is far too long to include here, but you can peruse his bio on the Library’s website, and then ponder sorrowfully how you yourself have frittered away your allotted time on this earth. Each Librarian brings his (so far it’s only been His) distinctive interests and talents to the post, thus enriching the Library.

Possibly the best known Librarian of Congress—the “Father” of its modern incarnation—is Ainsworth Rand Spofford (served 1865-1897), who increased the Library’s collection dramatically AND acquired for it a new home.

Spofford, born in New Hampshire and homeschooled (homeschoolers take note), was clearly headed for a life among books—avid reader, bookstore clerk, a founder of the Literary Club of Cincinnati, newspaper reporter and editor, and finally Assistant Librarian, then Librarian, of Congress. He managed to get the Smithsonian’s vast library transferred to the Library of Congress, and he persuaded Congress to pass a copyright law of 1870 that centralized all U.S. copyright registration at the Library—huge in itself!—and also required authors to deposit in the Library two copies of every book, map, print, and piece of music registered in the United States. (The copyright protection law extends even to works of foreign origin, with reciprocal protection. But there is apparently nothing the Library of Congress, or anyone else, can do about peculiar Chinese versions of Harry Potter that incorporate Chinese wizards, hobbits, and a belly dancer.) As you might guess, even if you have not a mathematical mind, such a law rapidly increased the Library’s collections.

A terrible fire on Christmas Eve, 1851, apparently due to a spark from an unattended fireplace, had, sadly, destroyed about two-thirds of the Library’s contents, including much of Jefferson’s original library. But the collection had been replenished in the 1850s, and by now the Library was stuffed to the gills. Over its history it had been moved around the Capitol, in and out of various spaces, to accommodate its growth. But the moment had come—the moment that we ourselves experience when we say, “I cannot put one more dishtowel into this kitchen drawer! We need to move!” And Spofford recognized that moment.

Library of Congress-Part 1

On this day in 1800, President John Adams approved legislation appropriating $5,000 to fund a hitherto nonexistent Congressional library.

Now, when the United States was young and the ink was still drying on the [mostly] ratified Constitution, its first Congress met for a short while (1790 to 1800) in Philadelphia. This contender for the role of Nation’s Capital was merely a disappointed temporary location, resigned to the government’s eventual transfer south. In the meantime, however, Philadelphia was, thanks largely to William Penn and Benjamin Franklin, a highly livable city—the most populated in the country (Washington, DC wasn’t even in the Top Twenty), with paved and lighted streets lined with sidewalks, fine masonry buildings, a university, a hospital, a fire department, gardens and parks, theaters and shops and philosophical societies and libraries—much like today, but without WiFi. The Library Company of Philadelphia offered the use of its fine collection to members of Congress free of charge, at a time when library use was by paid subscription.

When the government packed up and trudged southward to the Potomac in 1800, they said to one another in despair, “Where in this muddy village of farms, taverns, and unfinished government buildings will we do the research and study necessary for Congressional legislation and malediction?”

Fortunately, the previous Congress had been planning ahead, and in 1801, a collection of 740 books and three maps, purchased with the appropriated funds, arrived from London. They were stored, along with the papers Congress had brought from Philadelphia, in a room of the partially-built Capitol Building. It was primarily a collection of legal, economic, and historical works. The next President, Thomas Jefferson (He Who Must Not Be Named in Texas), a voracious scholar himself—if there was any subject that never interested him it is apparently unrecorded—signed a law creating the post of Librarian of Congress.

Fire is a perpetual threat to the flammable cities of civilization, and disaster can result merely from an unsnuffed candle. The Library has suffered from several, mostly minor, fires. But in August 1814, during the War of 1812, the British set about destroying Washington’s public buildings, to avenge the Americans’ destruction of the public buildings of Toronto. Although parts of the Capitol held up remarkably well, its interior, filled with wooden furniture, paintings, and irreplaceable documents and books, was highly flammable. That was the end of the library.

But only temporarily. Because Jefferson, now in retirement and short of cash, offered to sell his personal library to the U.S. government as the foundation of a new collection. So in 1815 he was paid $23,900 for his 6,487 books, which arrived by horse and wagon from Monticello.

What a collection it was. Not only works of law, economics, and history, to replace the lost books. But also: Biography. Geography. Chemistry. Botany. Medicine. Anatomy. Architecture. Philosophy. Painting and sculpture. Theater. Music. Literature. Essays. Mythology. Religion (including a copy of the Koran). And not only in English, but also works in French, Spanish, German, Latin, Greek, and Russian, several of which languages Jefferson spoke or read.

Some members of Congress objected to the collection’s breadth, explaining rather myopically, “the library was too large for the wants of Congress,” but Jefferson famously responded, “There is…no subject to which a member of Congress may not have occasion to refer,” and that statement has guided the Library in its acquisitions over the years.

Morning Paper

The Tomes They Are A-Changin’

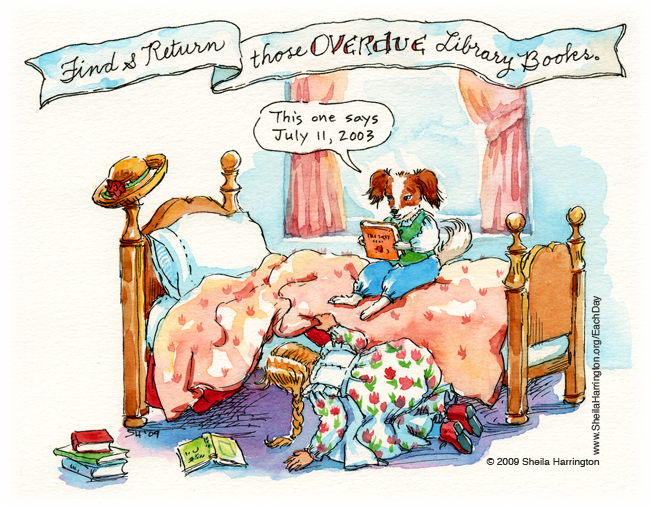

New Year’s Resolution: Library

On my list of things for which I am grateful is the public library, which I consider one of the greatest blessings of modern civilization and which is one of the first things I think of when I pay taxes. I have memories of libraries going back to childhood and recall wandering the stacks in cool semi-darkness, making my selections, then walking home on a hot summer day with a stack of well-worn cloth-bound books, prepared to curl up and enter other realms. Now I see my children with the same passion, choosing the library as a pleasurable destination: “Can we stop at the LIBRARY?” A world of wonders open to us all, free of charge. Thank you, Andrew Carnegie! Thank you, dear Library and Librarians everywhere!