I am sad to tell you that tonight is the night of the Perseid meteor shower. Sad because here we have pouring rain and crashing thunder; not the best conditions for viewing.

A meteor shower is the debris shed by a comet as it orbits the sun, and we on Earth pass through several showers of comet-debris during the course of each year. When one of the meteors happens to enter our atmosphere, it is traveling at such a tremendous rate (thousands of miles an hour) that it’s ignited by friction—giving the impression of a falling star—and generally burns up before it hits the ground. (Sometimes a meteor makes it all the way to Earth without being consumed, in which case it is termed a meteorite. A few very large meteorites have made impressive dents in our planet.)

The Perseids are the meteors of the comet Swift-Tuttle, through whose rubble we pass in August. They are named for the constellation Perseus, because from Earth’s perspective they seem to be coming from that direction. In mid-August in this hemisphere Perseus rises in the northeast at around 11 pm or so. This year, August 12th, starting at around midnight, is supposed to be the best time for viewing the Perseids. Ha! Well, probably some of you live where it is not raining.

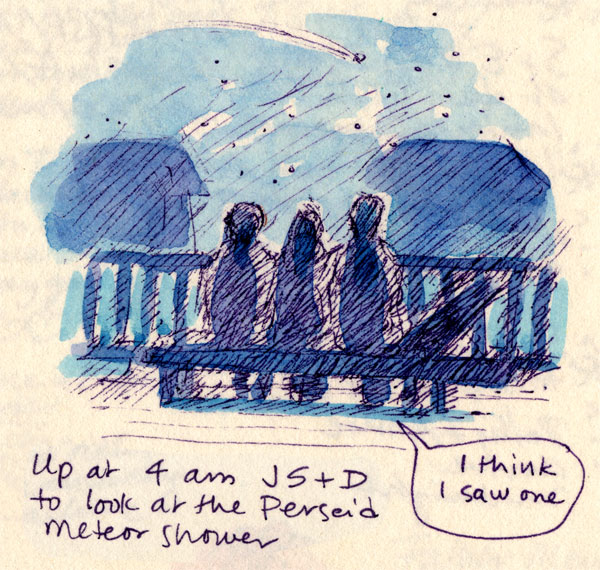

To view a meteor shower, it’s best to get out of the city or densely populated suburb—in other words, head for an area without lots of artificial light. In past years we have set the alarm clock (sometimes the best time is 3 or 4 am) and then gone out to sit on a deck, or lie on a rooftop, or stretch out in a big treeless field on a blanket (or, if in Vermont, shivering under the blanket) and then waited, gazing at the night sky.

Some years we’ve seen many, many. Other years (as above) we’re not so lucky. But go do it anyway. How often do we even take time to look at the Milky Way? That in itself is a rare and wonderful experience for the frazzled urban person. The additional sight of sparkling shooting stars sailing across the night sky is seriously magical.