This is my daughter’s drawing of the aforementioned beech tree fungus. She’s done a better job than I did of bringing out its liveliness and color. It now merits a classier name than “fungus.”

Tag: Homeschooling

Fungus, beech tree

My daughter and I have walked past this beech tree fungus all summer, and we finally stopped one day with our pencils and paper and drew it. The depression in which the fungus growing (which I assume marks a fallen branch) is about ten inches high, and the fungus is surprisingly colorful. My drawing doesn’t really do it justice. My daughter’s is better—I will put that up next week.

Lichen

One of the goals of our Botany block is to explore the range of plant categories we find in our immediate surroundings, wherever we happen to be, from fungus and seaweed to flowering plants and trees. This was our first study of lichen, discovered growing on a fallen twig, and it was quite small. But the more closely we looked, the more we saw.

Lichen is actually two plants, a fungus and an alga, working symbiotically: the fungus provides housing for the alga, and the alga provides food for the fungus. Like many traditional marriages.

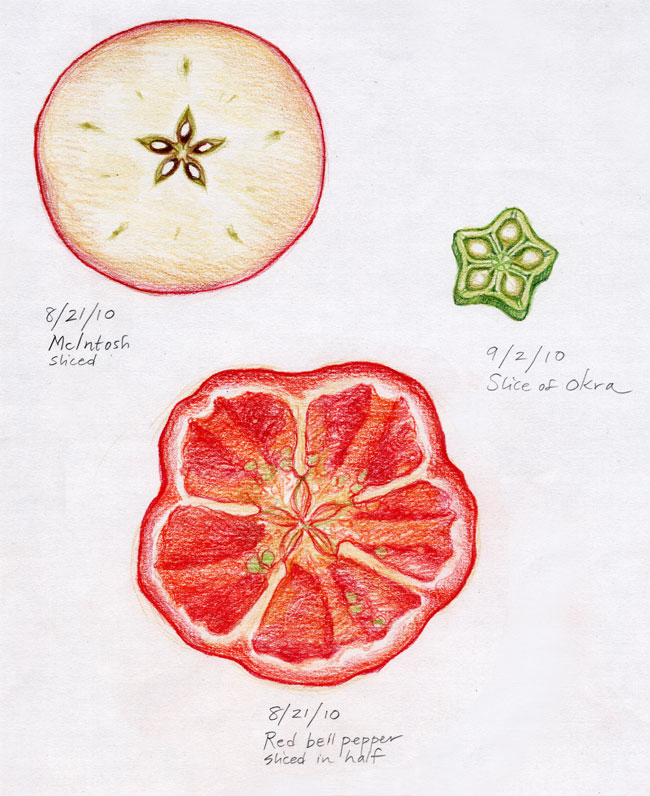

Hidden Stars

Some of these summer days have been too hot and mosquito-laden for sketching outside, even early in the morning. So, for our Botany block, my daughter and I have been indoors slicing through some of the fruits of the season, to find the surprises within. Circles! Triangles! Stars! (I’m hoping this will lead very naturally into 6th grade Geometry…)

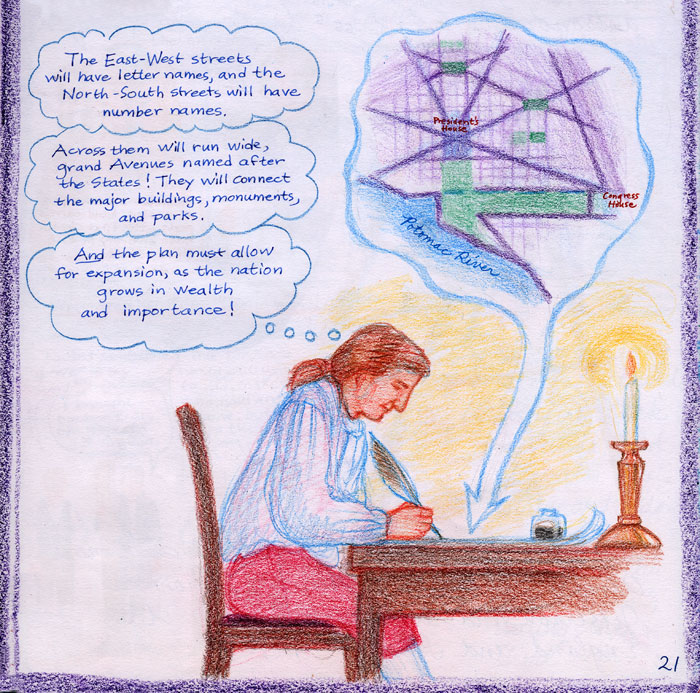

The Man with the Plan

Here is a drawing from our homeschooling Local History and Geography book, in honor of Pierre Charles L’Enfant (1754-1825), whose birthday it is today. Because of other obligations I cannot give him the lengthy post he deserves, but I hope to do him justice in 2011.

L’Enfant, an artist and son of an artist, came from France with the Marquis de Lafayette, as most Washingtonians probably know, to fight alongside the American colonists for independence, and later, having impressed the General with his battlefield sketches, was appointed by George Washington to design the United States’ new capital, Washington, DC. He created a a plan which was unfulfilled during his lifetime and has been only incompletely followed since, but which nevertheless gives us today this lovely and unusual city.

L’Enfant examined a quiet, hilly site of woodland, meadow, and marsh, uninhabited but for a handful of farms and the tiny port of Georgetown, and visualized an orderly grid overlaid by wide diagonal avenues allowing for long vistas, designed to incorporate stately public buildings, canals, bridges, squares, parks, and monuments: not simply a new bureaucratic center, but a Grand Capital for a young, energetic New Nation.

He had also a number of sensible, intelligent ideas as to how construction of the new city might have been financed, which were unfortunately never followed. Reading about the snail-like early development of the city, its wrangling political factions, its stodgy unimaginative Commissioners, and its greedy unscrupulous speculators, would make your hair stand on end. It also sounds uncomfortably familiar.

In the midst of it L’Enfant and Washington kept before them the vision of a finished work. Along the way L’Enfant, a hot-headed and demonstrative fellow, offended any number of people by vehemently defending his plans against unattractive provincial alterations (like any artist worth his salt) to the point of knocking down a new house that intruded on one of the proposed avenues. Not the way to keep your job. Which he finally lost after an exasperated Washington could no longer defend him against his many critics. L’Enfant remained bitter about his treatment—he was never paid for his work, although others made considerable sums through its implementation—and spent his remaining years as the poverty-stricken guest of a kind friend in rural Maryland, to be buried finally in their garden.

He has since been removed to a more honorable site in Arlington Cemetery, overlooking the city that finally rose to meet his expectations. Happy Birthday, Pierre, and I hope you are enjoying the view.

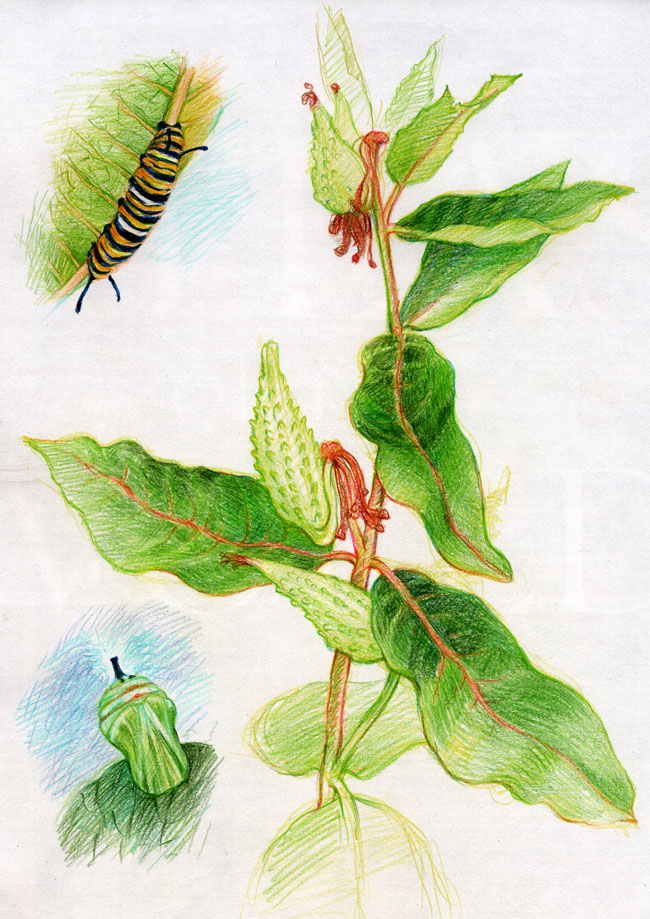

From Milkweed to Monarch

While house-sitting for friends in Massachusetts, we took care of Flute, their parakeet, and two caterpillars in the dining room. The caterpillars lived on fresh milkweed leaves from the garden. And they sure put away a lot of leaves, chewing audibly beside us during mealtime (and apparently all the rest of the time).

One day they stopped eating and attached themselves to the side of the terrarium, quiet yet pulsating, and seeming to shrink inwardly, their festive green and yellow bodies growing dark and shriveled. I stayed up as late as I could and finally had to crash. In the morning those discarded husks lay on the floor, each replaced by a gleaming jewel-like chrysalis.

Flute was a much jollier and more sociable companion, riding about on our shoulders and chatting throughout the day, but the caterpillars were a (mostly) silent reminder of the daily small miracles that surround us.

Peas of Mind Part II

(Continued from Peas of Mind Part I, July 20)

Speculation on this subject probably dates from prehistory, when nomadic peoples discovered that fallen seed produced new grain, and that it was handier to domesticate sheep than to chase after them in the wild. Selective breeding of plants and animals is thousands of years old.

But how did it all work? Why did sheep vary in color, size, and wool quality? For that matter, why did sheep give birth to lambs instead of, say, lentils? Was it all an unchanging predetermined system, set in motion by a Creator? Was variation due to inner mechanisms, or to external factors, like environmental requirements, or supernatural forces? Did new species generate spontaneously, from water, mud, cheese, and old rags? Was there an underlying material explanation for the workings of the Great Chain of Being?

Every people has had its explanation for the workings of existence. From mythology to religion to philosophy, theories abound. And as the world has shrunk and human consciousness evolves, explanations are increasingly shared, expanded, and abandoned.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, the Western world was seized with a new fever of questioning in all areas of natural science. By the 19th, scientists working independently in diverse fields were moving inexorably from childlike faith in mythology and magic toward a secular, observation-based, material Explanation For Everything. It was the early adolescence of Western thought: Ha! You don’t know everything, God, so I’m going to search for the truth myself! And maybe I’ll find out you’re not even there! Questioners sought to discover universal underlying principles of existence, revealing that they retained a desire for Oneness through science that would replace loss of faith. But that’s another post…

So back to Mendel and his peas. (I realize this is my SECOND post about a monk this month! but that is pure coincidence.)

Pea plants are self-pollinating, but Mendel controlled pollination by removing stamens from selected plants and pollinating specific generations by hand, controlling for one characteristic at a time and keeping detailed mathematical records of the results. His experiments revealed consistently that, although the offspring of a first generation of peas always resembled the parents, the offspring of two crossed generations resembled only ONE parent—and, most surprising, that among the offspring of the hybrids, three out of four peas displayed one parental trait and the fourth pea displayed the other.

Other scientists had previously studied cross-pollination, but without coming to final conclusions or developing laws of inheritance. But Mendel, after growing thirty thousand plants over eight years, deduced the existence of what he called dominant and recessive traits, controlled by elements within the egg cell and the pollen of plants (later called genes). He also concluded that each parent carries half the elements passed on to offspring, and that these individual elements remain present and distinct, controlling specific characteristics like eye and hair color. (We’re no longer talking about peas here, except for unusual, Pixar-type peas.) This was in contrast to others, including Charles Darwin, who thought that characteristics from parents blended within the offspring.

In 1865 Mendel presented his findings to the Natural Sciences Society of Brünn, and later mailed printed copies throughout the scientific community (Darwin got one), but he received little response. Some fellow scientists were confused by his mathematical approach and his talk of distinct inherited traits. And what did peas have to do with people? Mendel was disappointed, but shortly thereafter he was elected abbot of the monastery, and although he continued gardening and beekeeping, his duties left no time for further experimentation. His position, however, now made possible financial assistance for his sister’s children (and a fire house for his home village).

Upon Mendel’s death, his successor burned his papers. (Horrors! I bet there’s a secret story in that.) Fortunately, the papers Mendel had mailed abroad survived. But it wasn’t until the early 1900s that his work was rediscovered by several scientists working independently of one another in Holland, Germany, England, and the United States, taking them by surprise. His work was challenged and his theories modified, but he had grasped certain basic principles of heredity fifty years ahead of anyone else, and terminology was developed for the field of study Mendel had initiated and the mechanisms and processes he had described.

Even though middle school was a LONG time ago, I cannot see peas in a garden without thinking of dear Gregor. Sigh. Including these delicious sugar-snaps growing in our friend Susan’s Vermont garden, which my daughter and I sketched for our Botany block. We picked and ate plenty of them, too. That was for our Gastronomy block.

Seaweed

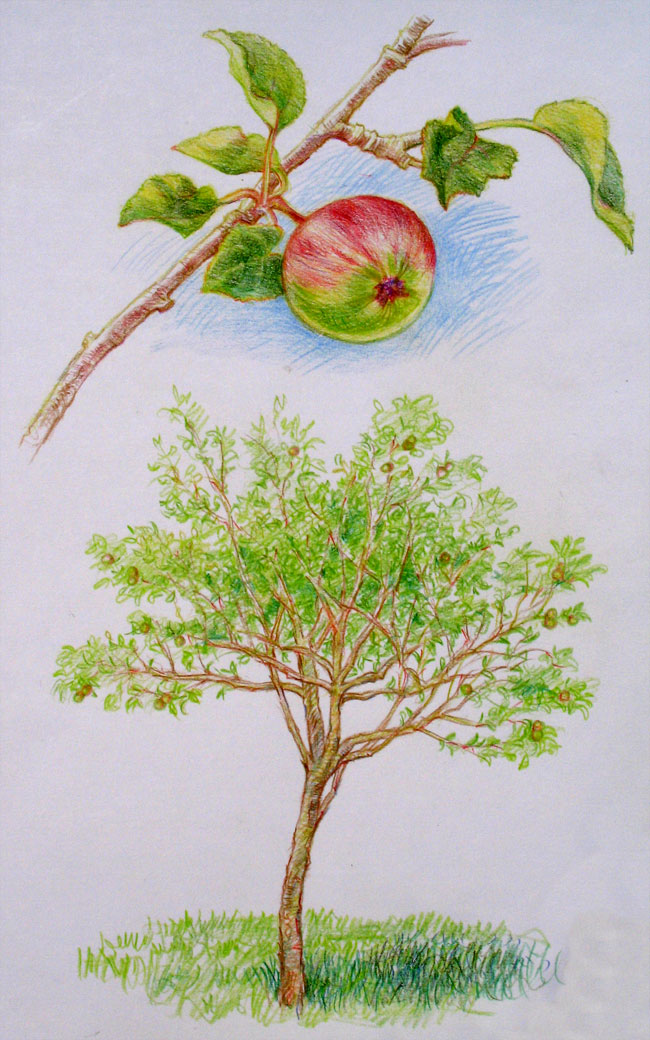

Apple tree

For Botany today we wander the apple orchard, examining the branches with their swelling fruit; then we sit beneath one of the trees and draw. Flies buzz overhead, birds sing in the woods nearby, and the dog stretches out on the grass for a rest. That’s what I call Natural Science.

Behold the apples’ rounded worlds: juice-green of July rain, the black polestar of flowers, the rind mapped with its crimson stain.The russet, crab and cottage red burn to the sun’s hot brass, then drop like sweat from every branch and bubble in the grass.

They lie as wanton as they fall, and where they fall and break, the stallion clamps his crunching jaws, the starling stabs his beak.

In each plump gourd the cidery bite of boys’ teeth tears the skin; the waltzing wasp consumes his share, the bent worm enters in.

I, with as easy hunger, take entire my season’s dole; welcome the ripe, the sweet, the sour, the hollow and the whole.

—Laurie Lee