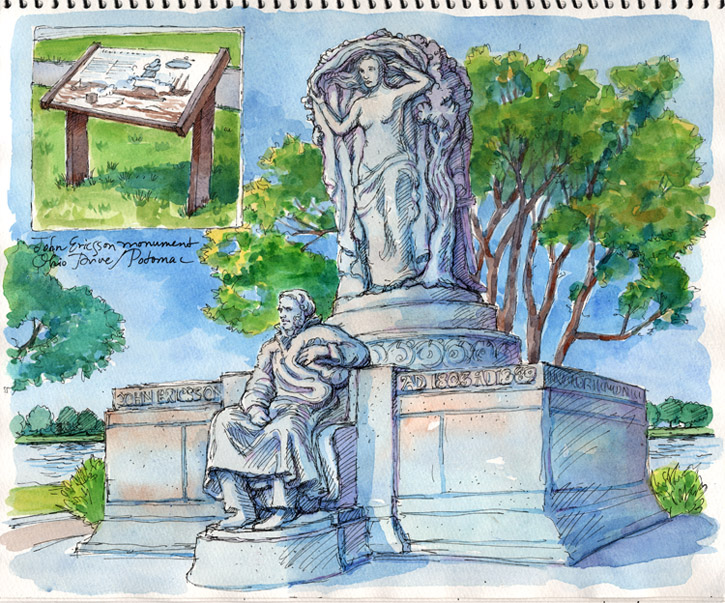

Where in Washington, DC—a city not known for its ancient fanciful mythology, except of the political kind—can you find an outdoor sculpture of Yggdrasil, the World Tree of Norse legend?

If you are zipping along in a car, you’ll miss it. But if you are traveling by foot or bicycle, you can take a break on a small green island (which I discovered by accident on a family bike ride, and returned to sketch) at the intersection of Ohio Drive and Independence Avenue, along the Potomac River. There at the foot of Yggdrasil sits John Ericsson (1803-1889), whose birthday it is today.

Ericsson, born in a Swedish village and son of a mining engineer, was a precocious child who demonstrated early an aptitude for all things mechanical. At five he created a working windmill from clock parts and household utensils. There is no historical record of his mother’s reaction to the missing tableware. At eight his education included informal instruction from his father’s engineering colleagues, and eventually he joined the team (although still too small to reach all the equipment), drawing up plans and supervising crews. During a period in the army he worked on designs for steam and fume-propelled engines, but finding no funding he took himself to England (leaving behind an out-of-wedlock son to be raised by his mother), which was then the hub of the Industrial Revolution and a showcase for new canals, railways, factories, and every sort of engine and mechanical device.

But despite his innovations in locomotive and marine engine designs, and his best-known creation, the screw propellor—which rendered vessels far more efficient and whose descendants are still in use worldwide—the English were unresponsive, perhaps because of Ericsson’s reputedly uncompromising nature, or perhaps because of his foreign origins. So Ericsson (leaving behind an English wife) betook himself to the young United States, with its energetic, ambitious entrepreneurs, and settled in New York, where pretty much everyone had (as today) foreign origins.

Here Ericsson sought supporters within the Navy and private industry for his screw-propellor vessel designs. He also tried, unsuccessfully, to interest the French Emperor, then engaged in the Crimean War, in a new rather peculiar-looking design for an iron-clad vessel (iron-clad ships having shown their effectiveness against the traditional wooden model).

But it was the American Civil War that delivered his opportunity. When the Southern states seceded from the Union in 1861, taking with them the Navy Yard at Norfolk and the USS Merrimac, which the Confederacy began to sheath with iron, it became obvious that the U.S. needed its own ironclad ship to protect the Northern coastal blockade. Ericsson’s industrial business contacts, who saw war as a terrific opportunity to increase their fortunes patriotically, used their influence within Congress and the U.S. Navy to advocate the implementation of Ericsson’s ingenious design, negotiate a contract, and launch construction of a vessel, in an unbelievably short period.

Ericsson’s ironclad ship (named the Monitor by Ericsson, as it was intended to monitor the coastline), with its iron sheath extending below the water line, its revolving turret that permitted it to fire in all directions, and its screw propellor, kept iron works, foundries, rolling mills, and manufacturers busily employed for months. For the sake of speed, some of its innovations (such as the underwater torpedo) were set aside, to be adopted later. Some were ignored, to the ship’s peril, as we will see.

Because the strange new vessel was untested, its crew was composed primarily of volunteers. Some observers (untutored in the laws of physics) predicted she would sink instantly when launched on March 6, 1862, headed for Norfolk. However, although the Monitor endured rough weather (and leaks, due to the Navy’s having ignored Ericsson’s instructions for the turret’s sealing), she arrived safely in Hampton Roads on March 8th, to find disaster: two ships already destroyed by the Confederacy’s Merrimac, and two others run aground awaiting their own coups de grâce.

For, during the past few months, the Confederacy had been hurriedly adapting the Merrimac (which they renamed the Virginia), preparing it to ram and sink the Yankee ships at Hampton Roads, to break the blockade and enable the resumption of Southern trade. Because the Union and the Confederacy were both riddled with spies, each knew something of the other’s ship-building progress, so perhaps it is not simply an amazing coincidence that the two vessels were completed and launched only a couple of days apart. In any case, news of the Merrimac’s success ran through the telegraph lines, thrilling the South and alarming the North, who feared that the Merrimac would next turn northward to destroy its coastal cities. This was impossible; the Merrimac was clumsy, leaky, and barely seaworthy enough to have made it across Hampton Roads. But the North didn’t know that.

When the Merrimac returned to finish off the last two vessels, it found a small, oddly shaped object—the Monitor—pluckily barring its way. At first the Merrimac’s crew believed the Monitor to be a supply barge, until it fired upon them. Battle between the two ironclads continued for several hours, with each trying to inflict damage upon the other, the Merrimac attempting simultaneously yet unsuccessfully to attack the nearby remaining Northern ships. The Monitor, small, nimble, and quick, protected the ships from further damage, and eventually the Merrimac retired leaking to its port.

Both sides (naturally) declared victory in the battle, but the ultimate outcome was a contract between John Ericsson and the U.S. Navy for a fleet of ironclads, and the successful blockade of the South. The poor Monitor, however, caught in a storm at sea later that year (the Navy still ignoring Ericsson’s instructions on the proper sealing of its turret), went down with sixteen hands off the coast of Cape Hatteras. (Some of her artifacts have since been recovered and conserved.)

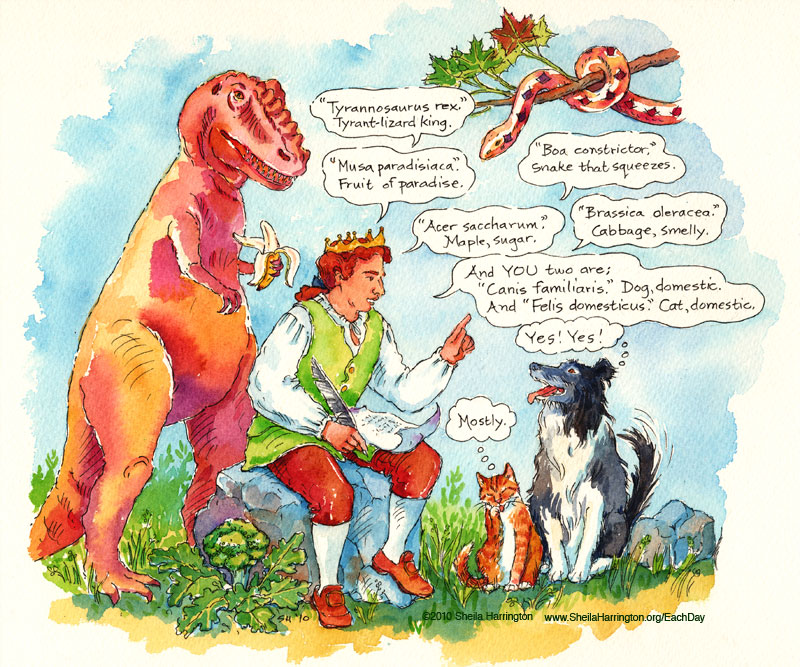

Ericsson, who had had a number of professional disappointments, was now vindicated and rewarded, and went on to work in maritime and naval technology and experiment with various sources of power—steam, electric, solar. Three Navy ships have been named after him, and in 1926 the monument pictured above, created by sculptor James Earle Fraser, was dedicated to him. There sits Ericsson (curiously, looking inland rather than out over the Potomac) beneath the Norse World Tree, with Vision standing behind him, flanked by Labor and a Viking warrior. It’s one of your more surprising Washington, DC sculptures. Go have a look.

Although Ericsson regularly sent funds for the support of that son and wife back in Sweden and England, his true passion was engineering, and neither ever joined him in the New World. Thus his days and nights were uninterrupted by the distracting joys and troubles of family life. Ericsson had a reputation for being stubborn, imperious, and single-minded, and perhaps these qualities do not a family man make… but they might enable one to overcome opposition and discouragement and press forward undespairing. Happy Birthday, husband and father of the Monitor.