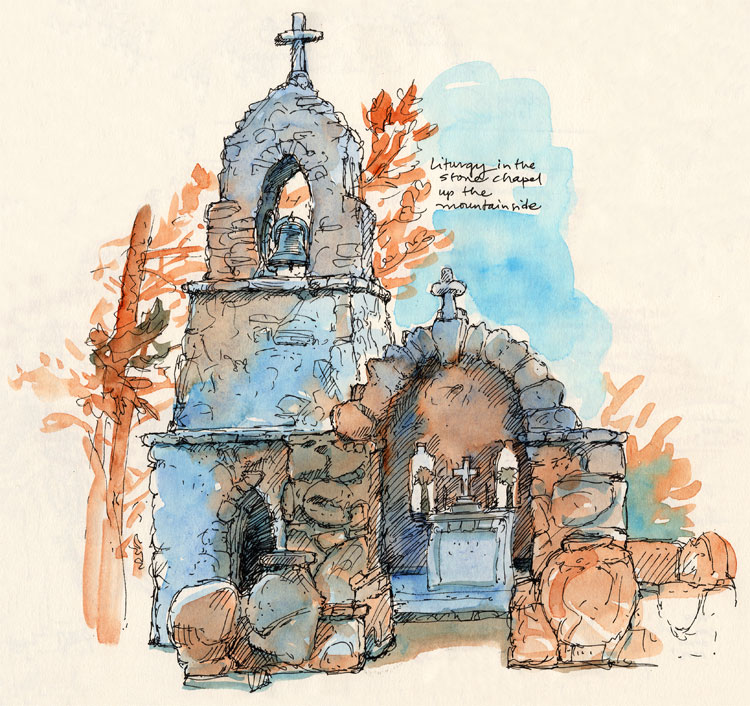

After a steep uphill trudge to a mountainside shrine, the rewards are worth the trek: the celebrant’s inspiring and funny thoughts to ponder; singing together among the birds and trees, everyone speckled with sunlight filtering through the autumn leaves; and at the end a quiet, inexpressibly affecting service for healing of body, mind, and soul.

Tag: Trees

Holy Water

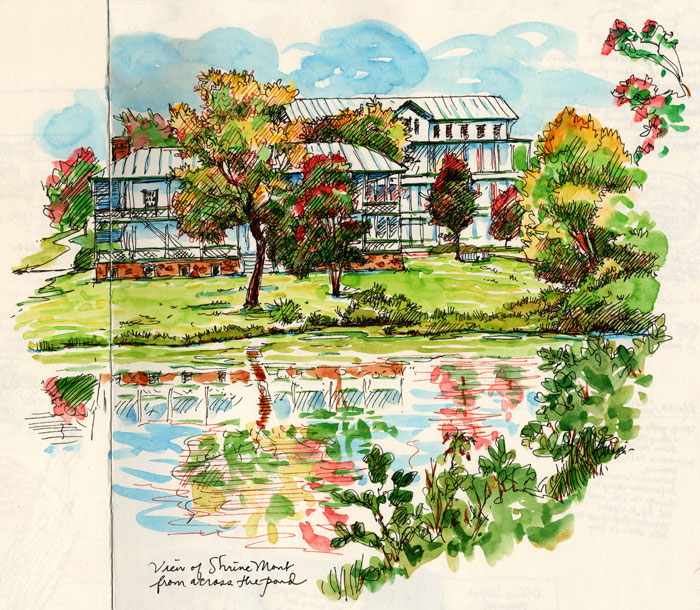

Our family is in the mountains with our church community for a couple of days of singing and dancing, meditation and prayer, and thoughtful discussion, interspersed with hay rides, hiking, and brownies. The accommodations are basic (hurray for indoor plumbing and hot running water!), and the food is definitely Lake Wobegon, but I always return with a feeling of good will toward all humankind and a renewed determination to do better at my part in it.

Here is a view of the pond, which, besides being restful for the spirit, is on Saturday afternoon the best place for children to immerse themselves in frogs and mud.

Golden

Fungus, beech tree

My daughter and I have walked past this beech tree fungus all summer, and we finally stopped one day with our pencils and paper and drew it. The depression in which the fungus growing (which I assume marks a fallen branch) is about ten inches high, and the fungus is surprisingly colorful. My drawing doesn’t really do it justice. My daughter’s is better—I will put that up next week.

Healing

Today’s post is in honor of dear and lovely Seska, married to Walter, one of my husband’s oldest friends (they were young adventurous guys together). She just had truly major surgery for ovarian cancer and will soon begin chemo.

Seska is many things—kind and sensitive social worker, artist and art lover, spiritual pilgrim, and determined optimist in the face of adversity. Most recently she has been working in post-earthquake Haiti, having accumulated a collection of musical instruments with which she has been helping children and adults to launch and re-launch music programs in schools and communities. Please keep her in your blessings, and think of her in your music-making.

This drawing is from Walter and Seska’s wedding invitation and seemed suitably hopeful. Their 14th wedding anniversary is later this month.

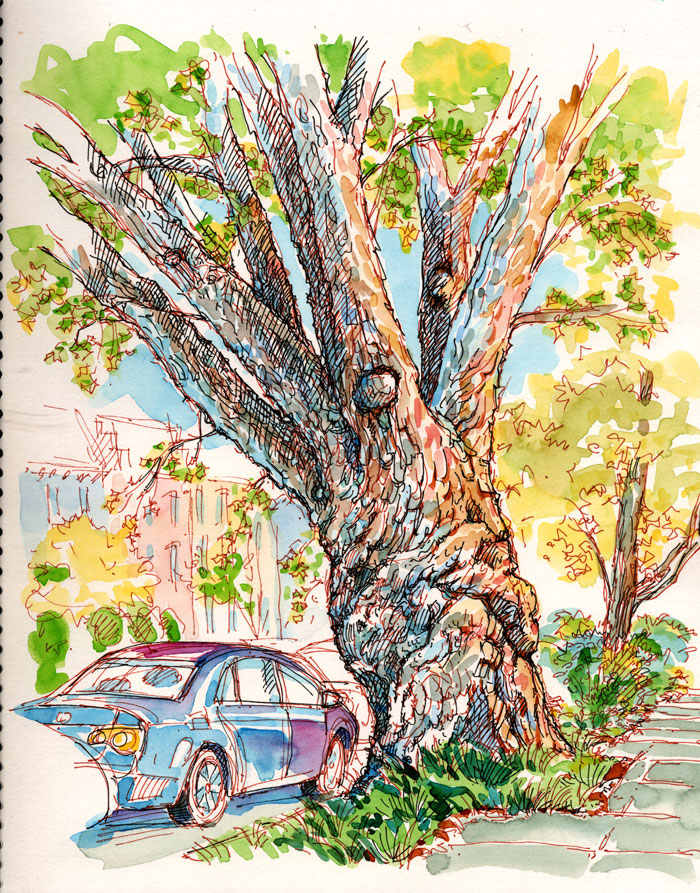

Tree of Life

I have ambivalent feelings about this tree. On the one hand, I never park under it, for fear that I would return to find my car crushed. On the other hand, it is the most powerful and heart-lifting tree in our neighborhood, with its fantastically sculpted trunk and enormous, light-filled crown, simultaneously shimmering and shady, undoubtedly home to innumerable beetles, birds, and squirrels.

After a recent summer thunderstorm, I went to check it out. There it stood, serene as ever, despite its permanent streetward slant. It’s a variety of maple (to find out what kind we’ll have to check Melanie Choukas-Bradley’s wonderful City of Trees), although it has the ancient, stalwart feel of an oak, as if it arose here here long before any of our houses.

Below, a tree poem for Sunday.

A Final Affection

I love the accomplishments of trees, How they try to restrain great storms And pacify the very worms that eat them. Even their deaths seem to be considered. I fear for trees, loving them so much. I am nervous about each scar on bark, Each leaf that browns. I want to Lie in their crotches and sigh, Whisper of sun and rains to come. Sometimes on summer evenings I step Out of my house to look at trees Propping darkness up to the silence. When I die I want to slant up Through those trunks so slowly I will see each rib of bark, each whorl; Up through the canopy, the subtle veins And lobes touching me with final affection; Then to hover above and look down One last time on the rich upliftings, The circle that loves the sun and moon, To see at last what held the darkness up.—Paul Zimmer

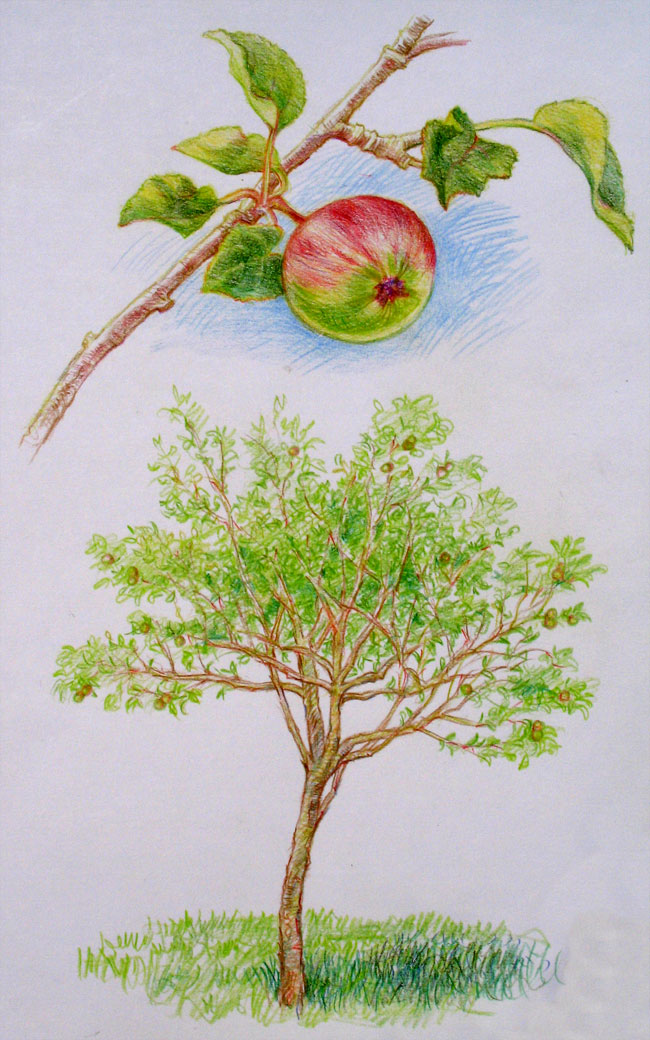

Apple tree

For Botany today we wander the apple orchard, examining the branches with their swelling fruit; then we sit beneath one of the trees and draw. Flies buzz overhead, birds sing in the woods nearby, and the dog stretches out on the grass for a rest. That’s what I call Natural Science.

Behold the apples’ rounded worlds: juice-green of July rain, the black polestar of flowers, the rind mapped with its crimson stain.The russet, crab and cottage red burn to the sun’s hot brass, then drop like sweat from every branch and bubble in the grass.

They lie as wanton as they fall, and where they fall and break, the stallion clamps his crunching jaws, the starling stabs his beak.

In each plump gourd the cidery bite of boys’ teeth tears the skin; the waltzing wasp consumes his share, the bent worm enters in.

I, with as easy hunger, take entire my season’s dole; welcome the ripe, the sweet, the sour, the hollow and the whole.

—Laurie Lee

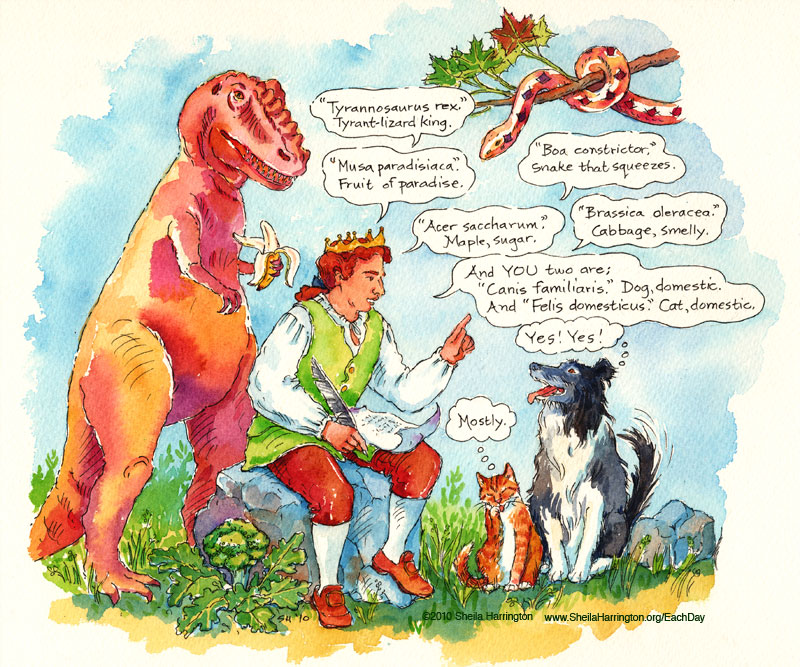

Prince of Binomial Nomenclature: Part 2

Continued from Prince of Binomial Nomenclature: Part 1, May 23rd

Longing to expand his perspective, Linnaeus applied for and received a grant for a field expedition to Lapland, a rugged region above the Arctic Circle, where he expected to find many unrecorded species. Linnaeus spent five months exploring and studying rocks, plants, insects, animals, and people, and returned with thousands of specimens (no people though), filled with excitement. He returned to lecturing, and planned a series of books cataloguing species according to his new system.

Linnaeus DID actually long for a reproductive life of his own. He paid court to a young lady whose father, not taking a wandering botanist very seriously, insisted that Linnaeus wait three years and meanwhile establish some means of supporting a family. So Linnaeus went off to Holland, whose universities were better equipped than those of Sweden, to complete his medical degree. He also found work there managing and classifying the contents of Dutch zoological and botanical gardens.

THEN, in 1735, while still in Holland, he published his book Systema Naturae, which explained his concept of classification. Linnaeus grouped plants and animals into genera—groups whose members have something in common, usually structural or related to reproduction. (Linnaeus was the first to classify whales as mammals.) Then he subdivided each group into species. (His complete heirarchy, as you may recall from high school, is Kingdom, Class, Order, Genus, and Species.) And then he gave each member a two-part name based on these divisions, replacing all previously-used cumbersome lengthy descriptions. These two-part names were in Latin, which was, and still is, the universal language of science. I told you those Latin classes would come in handy.

Systema Naturae hit the botanical world like a bolt of lightning. The notion that PLANTS (seemingly so innocent!) had a Sexual Life, by which Linnaeus partly categorized them, was outrageous and horrifying to some naturalists, and Linnaeus was criticized for “nomenclatural wantonness.” But, despite objections on both theological and moral grounds, Linnaeus’ achievement launched him from obscurity to fame. A binomial concept had been proposed by Swiss botanist Gaspard Bauhin in 1623 but was never widely used. When Linnaeus combined it with his new categorization methods, the idea spread rapidly. Here was a practical tool: reasonable, memorable, universally applicable. Not only could scientists from different countries know they were communicating about the same species; it was even easy for amateurs to use, and it sparked a more widespread interest in natural history. Such is the effect of nomenclatural wantonness.

Now back in Sweden as an established botany professor, Linnaeus was able to marry his fiancée, although he spent so much time away on expeditions that she might have been happier with one of her other suitors. He lectured, wrote many works on botany, corresponded with other naturalists, revised and expanded Systema Naturae many times throughout his life (it eventually reached 2,300 pages), led collecting expeditions, and inspired his students to travel throughout the world as botanical and zoological explorers. One circumnavigated the world with Captain Cook. Others went to North America, Japan, China, and Southeast Asia, returning with specimens (or occasionally dying in a distant land; collecting could be dangerous work). Eventually he was knighted for his contributions to science and became Carl von Linné. So there, Mom and Dad.

Linnaeus himself gave scientific names to 4,200 animals and 7,700 plants, generally choosing names to reflect physical qualities, but occasionally to honor a friend or colleague, or, with a particularly ugly or toxic specimen, to insult someone who had annoyed him. Be wary of affronting a botanist. They are still lurking out there today…naming species.

With some modifications due to our modern understanding of evolution, Linnaeus’ system is still in use today, and pretty much taken for granted. But whenever you say Homo sapiens, or Boa constrictor, perhaps now you will think of Carolus Linnaeus, who made it possible, and you will celebrate his birthday every May 23rd. If you weren’t doing so already.

Throughout his life Linnaeus was a deeply religious fellow. He saw his work as clarifying for the world the underlying connections among living things and confirming the intelligence of a great Creator. Ironically, however, because his work made possible far greater understanding and communication among naturalists everywhere, it led to observations of surprising patterns and eventually to the shocking speculation by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace that species, instead of having been from their Day of Creation exactly as we know them now, had perhaps changed over time. Over a long, long time. We do not know the ultimate consequences of our life’s work.

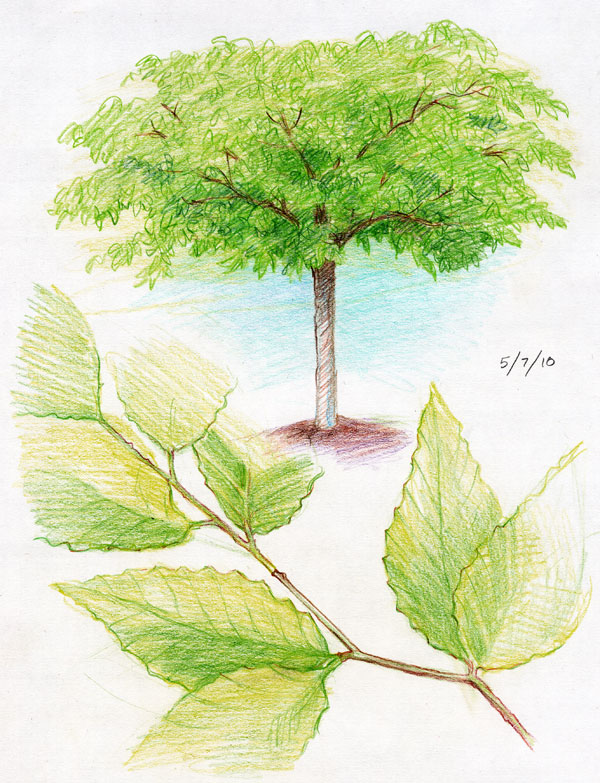

Mystery Tree

One of the projects of our homeschooling Botany block, which we began just before the spring equinox (and which looks like it will continue for a year, if we want to get a rounded view of plant life) has been a Tree Study. My daughter chose a tree in its winter state, down the street on the grounds of the hotel, and we sketched its bare branches and made crayon bark rubbings. Spring arrived; we sketched other, now-budding, even flowering and leafing trees; did other bark rubbings. Our Chosen Tree remained mystifyingly and unashamedly bare in a forest of showy blossoms and new green leaves. Good grief! Was it even ALIVE? Yet the reddish branch tips were springy, not dry.

One day the tips seemed a bit longer. The next day more so. Still no green, but increasingly long. Finally each tip gently opened to reveal a glimpse of…GREEN! Then, long clusters of large, fresh leaves unrolled themselves day by day, impossibly, from the formerly slender twiggy tips. In a few days the tree bore a bright and bushy yellow-green crown wider than it was high, well worth the wait. We sketched it in its new glory. Some of you must be familiar with this type of tree, but I only recognize a handful of varieties. Our neighbor Jason, seeing the sketch, revealed its identity: it is a hornbeam.

Busy Beaver

From my sketchbook (drawn across the gutter; sorry).

On a Memorial Day weekend hike through beautiful Prince William Forest Park in Virginia a few years ago, we saw many tree stumps ending in chewed points, surrounded by piles of wood chips, indicating the presence of beavers. And when we reached the creek, we did see several beavers, as well as a substantial beaver dam. What I couldn’t understand was why the stumps were so FAR from the water. A mystery.