Ah, Paris… The history! the art! the cafés! the romance of an evening stroll beside the Seine with the lights of the Tour Eiffel twinkling downstream! Unless, of course, you are among the artists, poets, and other French citizens of 1887 who were horrified to contemplete the erection of what one writer called “an odious column of bolted metal” that “even commercial America would not want on its soil,” and who together signed a paper protesting its construction.

Alexandre Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923) was born in Dijon, France, and after obtaining his baccalaureate came to Paris for further education. After the disappointment of rejection by the Polytechnique (take heart, aspiring applicants), he obtained a diploma in chemistry from the École Centrale de Paris and launched a career in metallurgy, a fortuitous choice at this exciting phase of the Industrial Revolution.

Eiffel was hired first to manage, then also to design, the construction of bridges. Within ten years he became an independent consultant and started his own company for the creation and construction of new large-scale iron and steel engineering projects. Because he was gifted as an engineer and construction manager, and the economy was booming, Eiffel was soon successful, rich, and in demand. He designed not only bridges but train stations, churches, lighthouses, palaces, and the armature for Bartholdi’s new Statue of Liberty. When a competition was held to design an iron tower for the Exposition Universelle de 1889, the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, Eiffel’s design was chosen from the 107 entries. Despite the aforementioned protests, Modernists and Republicans (as opposed to Monarchists) viewed the project with enthusiasm.

Construction began in January 1887, and the increasing fascination of the steadily growing tower foreshadowed its future popularity. It was completed in twenty-six months without a single fatality, and as the newly tallest structure in the world immediately drew crowds of visitors. (Amazingly, the weight of the tower per square inch is no greater than that of a man sitting in a chair.)

Eiffel went on to design other projects, including an ill-fated Panama Canal venture in 1887 that, through no fault of his, collapsed due to financial mismanagement. Discouraged, he turned from construction to experimental research (another of his passions). Eiffel had planned in advance multiple functions for the new tower, and he began a series of aerodynamic, meteorological and radiotelegraphic experiments to be undertaken from its height. In 1898 an antenna was mounted for radio transmission.

Originally planned for removal after twenty years, by 1907 the tower had become far too useful and admired. A new generation of artists now celebrated the Eiffel Tower in paint and literature. Who can envision Paris without it? Of all Eiffel’s work, this tower that bears his name is probably the most beloved. Happy Birthday, Gustave Eiffel! What a gift you have given to painters, photographers, filmmakers and lovers.

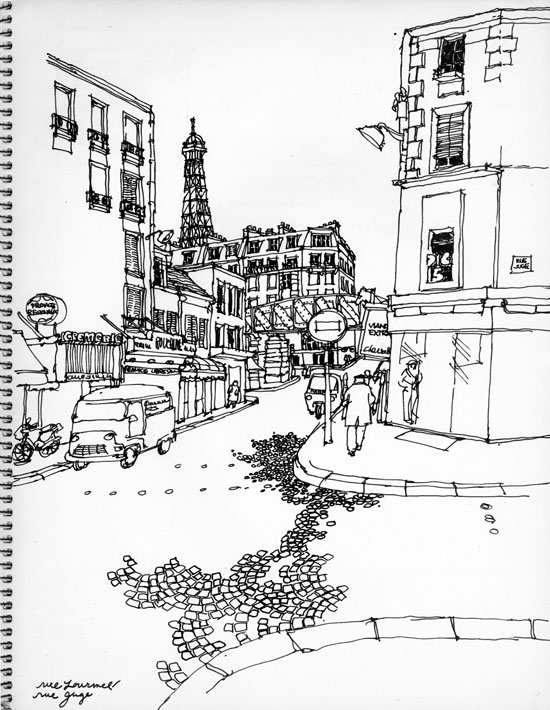

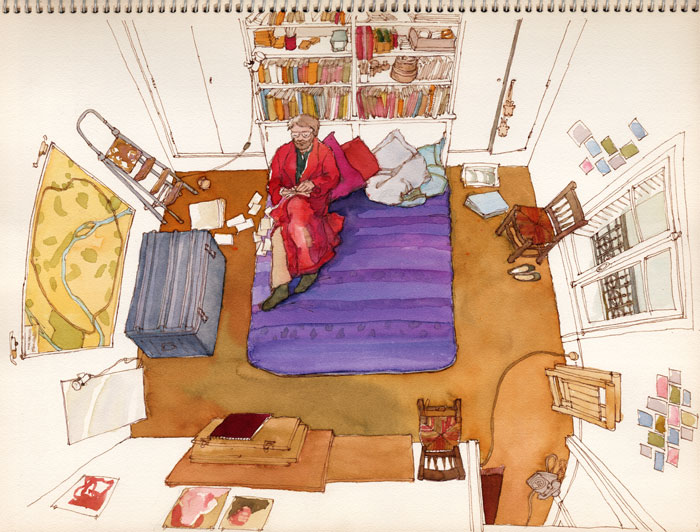

This sketch is from our old neighborhood in Paris.