When I travel, I like to see what Mass is like in other places, especially in foreign countries, now that it’s no longer in Latin and I can listen to the local language. Even if I don’t speak the language, the structure of the service is familiar enough that I know what’s happening. I guess that’s part of the appeal of standardized religions. It’s like being a member of a club, and you get to participate as long as you follow the rules, learn the secret handshake, and wear the moose hat.

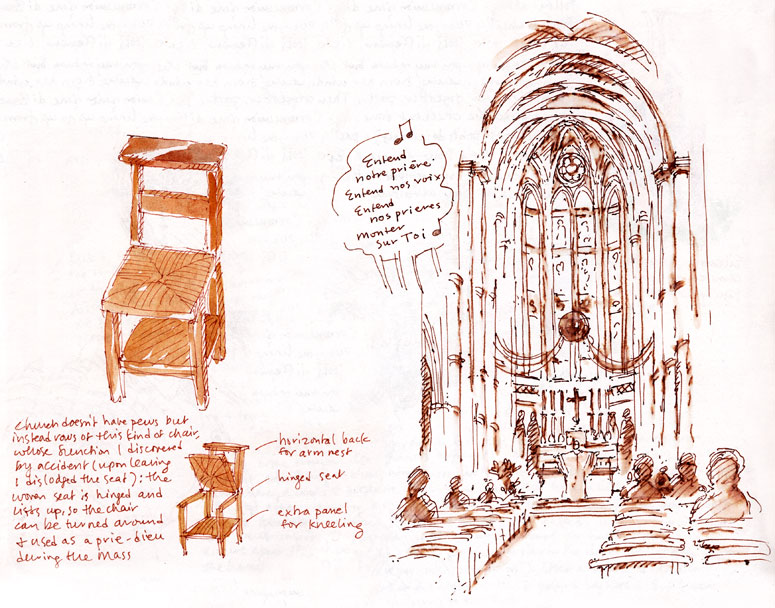

I did this sketch at a church in Epinal, France some years ago, and I post it here because it seemed suitable for today’s anniversary of the declaration of the Edict of Nantes in 1598. If this event does not leap out from the Renaissance history drawer of your brain, let me remind you.

In the 16th century, France was in the midst of its Wars of Religion. Just like many other nations whose boundaries we take for granted in our own lifetimes, “France” was an evolving entity torn by factions jostling for influence and supremacy, while ordinary peasants muddled along growing periodically-trampled cabbages as best they could. When the teachings of Martin Luther were introduced to France and were received with interest, even passion, by part of the population, it lit a fire in the hearts of others who (choose one):

a. were genuinely concerned about the immortal souls of these lost sheep.

b. feared the loss of power and riches that affiliation with the approved Catholic designation afforded them.

c. said, “Hey, here’s an opportunity to get rid of that rich relative/persistent creditor/tiresome spouse.”

d. foresaw that 36 years of people slaughtering each other and desecrating their forms of worship would be a jolly good way to spend their time.

(Answer is probably e.)

The Huguenots (French Protestants) and the French Catholics each spoke as if convinced of the one-true-faith-ness of their respective choices and sought not only to protect their own practices but to squash each others’ altogether. The neighbors were called in (Protestant England and Flanders; Catholic Spain and the Papal States) and arrived shouting, brandishing weapons, and eyeing the attractive lands near their borders. Numerous skirmishes, all-out battles, and horrible massacres alternated with periodic treaties and edicts which brought peace briefly and were then ignored.

Complicating this struggle was the irony that, not too far down the line of succession to the throne, was Henri of Navarre, a sword-wieldin’, skirt-chasin’, freedom-lovin’ mec* (worth an eventual post here) and a Huguenot himself. Catherine de Medici, mother of the young and unstable King Charles IX, was more practical than religious, and her principal aim was to keep control of France in her children’s hands. As what mother wouldn’t. She proposed a marriage between her beautiful daughter Marguerite and Henri of Navarre, and, despite disapproval from nearly everybody on both sides, the marriage took place in Paris. Followed immediately by the horrible St. Batholomew’s Day Massacre, the worst yet.

Henri was obliged to flee Paris, and when Charles IX died shortly thereafter, Henri had to fight his way back to Paris at the head of an army to be recognized as the new King Henri IV. He successfully conquered one region after another, but staunchly Catholic (or perhaps just relentlessly stubborn and contrary) Paris held out, eating rats du jour right through a siege, until Henri relented and decided to convert to Catholicism. This was not a big deal to him, as he had practiced both faiths while growing up depending on whether he was at court or at home. But it was a huge deal for the country, annoying both disappointed Protestants and skeptical Catholics.

Once he was ensconced, however, Henri showed the kingly stuff he was made of, launching a series of highly successful financial and agricultural reforms and huge public service projects. He then took the opportunity to enact what you, faithful reader (if you are still with me here), have followed this post so long to discover: THE EDICT OF NANTES, which authorized freedom of Protestant worship, the press, eligibility to public office (his brilliant finance minister was a Huguenot), and equal admission to schools, universities, and hospitals. It also authorized payment of Protestant ministers by the government. (This tolerance extended only to Protestants—forget Jews, Muslims, or atheists.) Simultaneously he allowed the previously exiled and troublesome Jesuits to return to France, taking one as his confessor. And he pardoned miscreants from both sides of the Wars of Religion. Thus Catholic and Protestant fanatics alike were infuriated.

But Henri’s intelligent policies and genial personality made him popular with ordinary folks, and France entered a new era of prosperity and relative tolerance that lasted until Louis XIV unwisely revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, resulting in a brain drain as thousands of Protestants took their skills and industry to friendlier locations. The 87-year period had been one step on the journey toward toleration of differences—a long and stumbling journey that, we must admit, is still in progress. Light a candle at dinner tonight in gratitude for each step.

*dude

If my grade school and high school history books had been as lively and – dare I say it – simultaneously irreverent and serious as your blog posts, Sheila, I would have discovered my inner love of history long before I did. Lucky Eileen, to have you as her history teacher.

Thank you for the encouragement!–I just hope Eileen feels the same way you do.