Today is the birthday of writer Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906), a once-upon-a-time resident of Washington, DC, and the child of former slaves. His father had escaped through the Underground Railroad and fled to Canada, returning to fight in a Massachusetts regiment upon the outbreak of the Civil War; his mother, freed by emancipation and on the verge of emigrating to Liberia, instead decided to remain in the U.S. when the war ended. They met and married post-war in Dayton, Ohio, where Paul was born.

Dayton was a 19th century rural-to-urban destination for southern African-Americans, who quickly established churches, schools, newspapers, and small businesses. Paul’s mother, sure that he showed promise, enrolled herself in night classes (during the day she worked as a cook and laundress) in order to be able to teach her son to read. She encouraged his early interest in writing, and he produced his first poems at age six and began reciting them publicly at nine. In 1887, Ohio abolished racial segregation in the school system (although extracurricular activities like plays and dances remained segregated), and Paul attended local schools as the only African-American student, serving as high school class president and writer and editor for the school paper.

Despite his excellent school record and his having had several pieces of work published in local newspapers, Dunbar found it impossible as an African-American to find either employment in journalism or funds for college. Instead he began working as an elevator operator in the Callahan Building, a seven-story “skyscraper” in downtown Dayton, writing in his spare time. A former teacher’s recommendation acquired him a place reciting his poetry at a convention in Dayton of the Western Association of Writers, and his writing and beautiful voice so impressed the listeners that a nationally distributed write-up of the event brought Dunbar broader attention.

His old school friend Orville Wright, who had dropped out of high school to start a small printing company—having built a press with his brother Wilbur (this in their pre-flight days)—helped Dunbar to self-publish a collection of his poems. Dunbar sold these to his elevator passengers for a dollar apiece, probably hoping that as many as possible would ride all the way to the seventh floor (“While you’re riding with me today, might I interest you in some poetry?”) and eventually recouped his investment. Lucky the buyer with the presence of mind to hang onto that first edition.

Travel and exposure brought Dunbar contacts and supporters, some of them fellow writers. On a visit to Chicago to write about the 1892 Columbian Exhibition, Dunbar met and was befriended by Frederick Douglass. With the patronage of a superintendent of the Toledo State Hospital, Dunbar went on to publish further collections of his work, which were also well-received. Dunbar wrote his poetry both in standard English and in southern dialect, which he had learned through stories from his mother’s Kentucky childhood; the use of dialect in his work has suggested comparisons with Mark Twain.

His growing reputation led to a series of recitals around the U.S. and eventually a six-month recital tour in England, where he also collaborated on theatrical and choral pieces and an operetta. When he returned, it was to Washington, DC and a position at the Library of Congress, meanwhile writing in his free time a collection of short stories and his first novel. The work at the Library was less rewarding than he had hoped, and a whole lot dustier, exacerbating his developing tuberculosis, and with his wife’s encouragement he returned to writing and reciting full-time.

The subject matter for Dunbar’s fiction was drawn from life in black America, and, despite its somber themes, tended to optimistic conclusions. Later criticized for somewhat stereotypical characterizations and a tendency to sentimentality, his writing was unusual in its exploration of the difficulties of African-Americans, both pre- and post-Civil War. In this respect, and particularly in his work in dialect, he influenced later writers of the Harlem Renaissance.

Sadly, Dunbar succumbed to tuberculosis in 1906. During his short life he produced nearly two dozen books: collections of poetry and short stories, novels, and other works. Nevertheless, one can’t help wondering what direction his writing would have taken had he been able to live beyond the age of thirty-three.

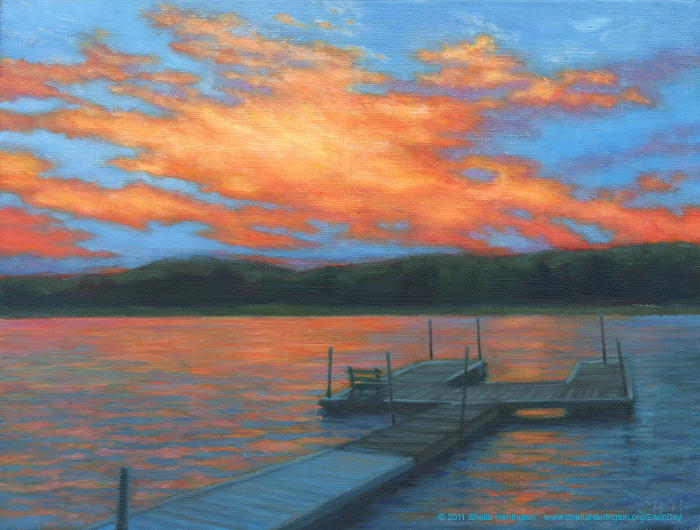

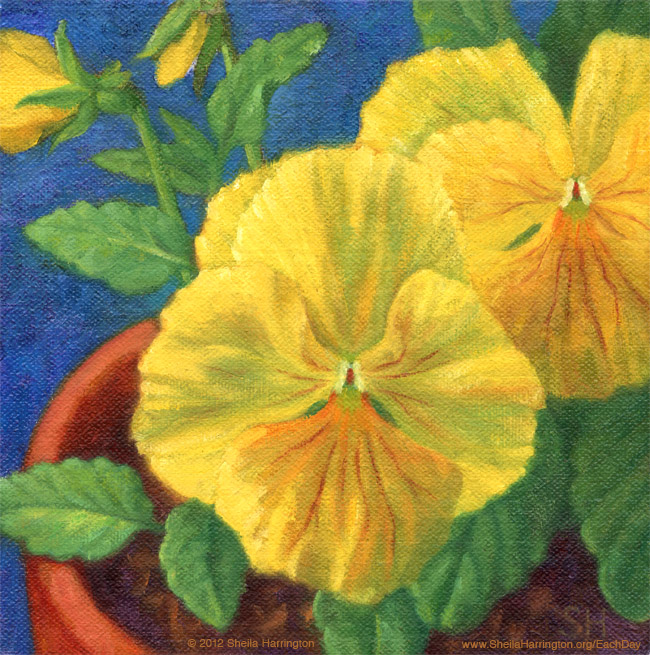

Here is one of his poems, “Summer in the South,” and a recently-completed painting to accompany it.

To see where Paul Laurence Dunbar lived and worked in the nation’s capital, you can consult the illustrated Literary Map of Washington, DC.

The oriole sings in the greening grove

As if he were half-way waiting,

The rosebuds peep from their hoods of green,

Timid and hesitating.

The rain comes down in a torrent sweep

And the nights smell warm and piney,

The garden thrives, but the tender shoots

Are yellow-green and tiny.

Then a flash of sun on a waiting hill,

Streams laugh that erst were quiet,

The sky smiles down with a dazzling blue

And the woods run mad with riot.

—Paul Laurence Dunbar

Agnès

Agnès