On the birthday of Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), I post this sketch made in the National Gallery of Art. It presents a theory about his work that I hadn’t previously encountered (and which might have surprised him).

Tag: DC

Birthday Girl

Croissant with Apricot Jam

Here is another of the paintings that I will be showing at the Corcoran Gallery’s Community Art Fair on Saturday, October 20th. (If it makes you hungry, take note that the Corcoran’s cafe will be serving a special menu created for this day.)

Corcoran Community Art Fair

On Saturday, October 20th, the Corcoran Gallery of Art will hold its first Community Art Fair from 10am to 3pm, featuring fine arts and crafts by local artists; workshops and demonstrations on papermaking, bookmaking, ceramics, and printmaking; concerts; films; and tours. I will be participating, showing some of the work I have featured on this blog as well as a small number of printed cards of my paintings (for smaller budgets). Admission is free but book donations are encouraged, to benefit Books for America. I hope to see many of you there!

This is one of the new paintings I plan to show.

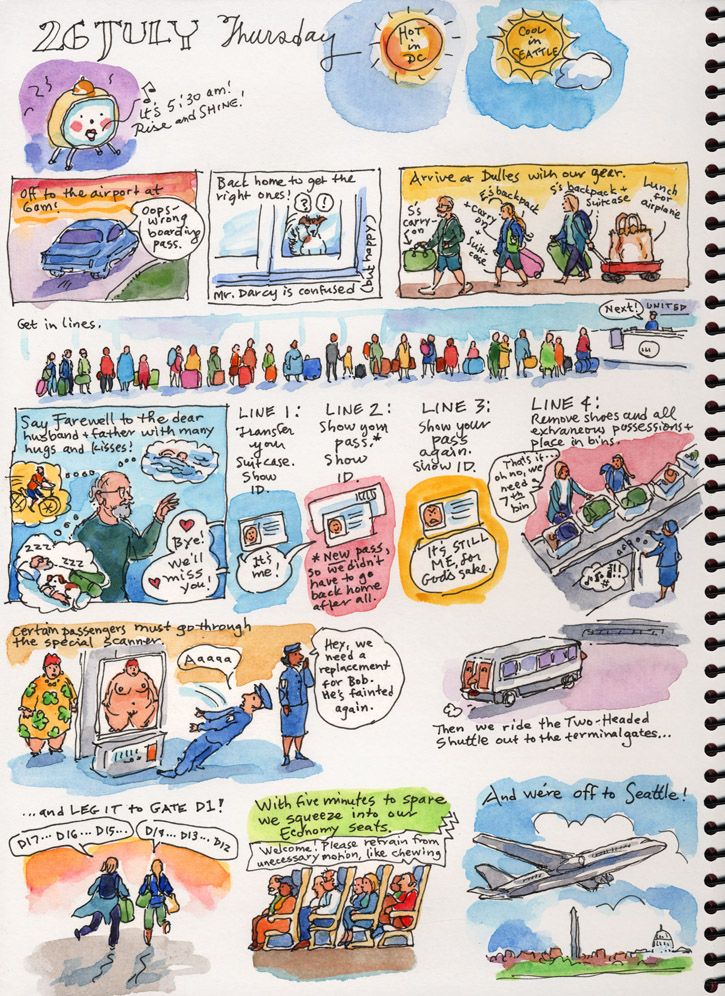

Westward Ho

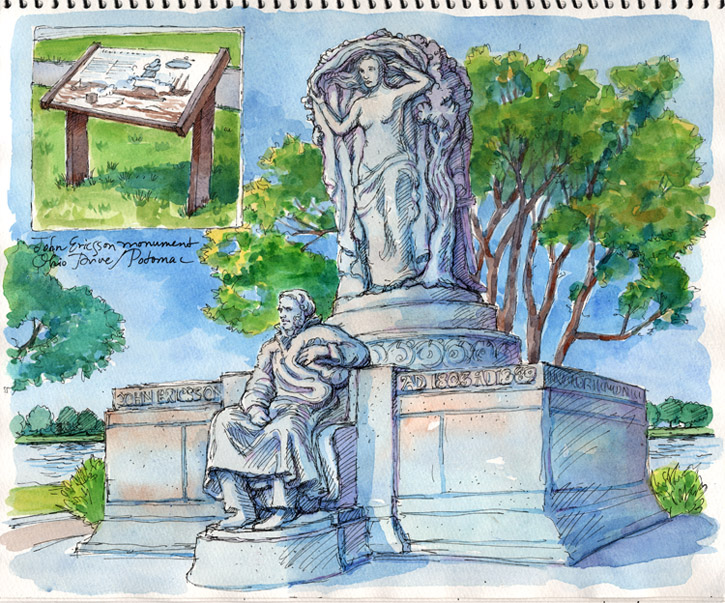

Father of the Monitor

Where in Washington, DC—a city not known for its ancient fanciful mythology, except of the political kind—can you find an outdoor sculpture of Yggdrasil, the World Tree of Norse legend?

If you are zipping along in a car, you’ll miss it. But if you are traveling by foot or bicycle, you can take a break on a small green island (which I discovered by accident on a family bike ride, and returned to sketch) at the intersection of Ohio Drive and Independence Avenue, along the Potomac River. There at the foot of Yggdrasil sits John Ericsson (1803-1889), whose birthday it is today.

Ericsson, born in a Swedish village and son of a mining engineer, was a precocious child who demonstrated early an aptitude for all things mechanical. At five he created a working windmill from clock parts and household utensils. There is no historical record of his mother’s reaction to the missing tableware. At eight his education included informal instruction from his father’s engineering colleagues, and eventually he joined the team (although still too small to reach all the equipment), drawing up plans and supervising crews. During a period in the army he worked on designs for steam and fume-propelled engines, but finding no funding he took himself to England (leaving behind an out-of-wedlock son to be raised by his mother), which was then the hub of the Industrial Revolution and a showcase for new canals, railways, factories, and every sort of engine and mechanical device.

But despite his innovations in locomotive and marine engine designs, and his best-known creation, the screw propellor—which rendered vessels far more efficient and whose descendants are still in use worldwide—the English were unresponsive, perhaps because of Ericsson’s reputedly uncompromising nature, or perhaps because of his foreign origins. So Ericsson (leaving behind an English wife) betook himself to the young United States, with its energetic, ambitious entrepreneurs, and settled in New York, where pretty much everyone had (as today) foreign origins.

Here Ericsson sought supporters within the Navy and private industry for his screw-propellor vessel designs. He also tried, unsuccessfully, to interest the French Emperor, then engaged in the Crimean War, in a new rather peculiar-looking design for an iron-clad vessel (iron-clad ships having shown their effectiveness against the traditional wooden model).

But it was the American Civil War that delivered his opportunity. When the Southern states seceded from the Union in 1861, taking with them the Navy Yard at Norfolk and the USS Merrimac, which the Confederacy began to sheath with iron, it became obvious that the U.S. needed its own ironclad ship to protect the Northern coastal blockade. Ericsson’s industrial business contacts, who saw war as a terrific opportunity to increase their fortunes patriotically, used their influence within Congress and the U.S. Navy to advocate the implementation of Ericsson’s ingenious design, negotiate a contract, and launch construction of a vessel, in an unbelievably short period.

Ericsson’s ironclad ship (named the Monitor by Ericsson, as it was intended to monitor the coastline), with its iron sheath extending below the water line, its revolving turret that permitted it to fire in all directions, and its screw propellor, kept iron works, foundries, rolling mills, and manufacturers busily employed for months. For the sake of speed, some of its innovations (such as the underwater torpedo) were set aside, to be adopted later. Some were ignored, to the ship’s peril, as we will see.

Because the strange new vessel was untested, its crew was composed primarily of volunteers. Some observers (untutored in the laws of physics) predicted she would sink instantly when launched on March 6, 1862, headed for Norfolk. However, although the Monitor endured rough weather (and leaks, due to the Navy’s having ignored Ericsson’s instructions for the turret’s sealing), she arrived safely in Hampton Roads on March 8th, to find disaster: two ships already destroyed by the Confederacy’s Merrimac, and two others run aground awaiting their own coups de grâce.

For, during the past few months, the Confederacy had been hurriedly adapting the Merrimac (which they renamed the Virginia), preparing it to ram and sink the Yankee ships at Hampton Roads, to break the blockade and enable the resumption of Southern trade. Because the Union and the Confederacy were both riddled with spies, each knew something of the other’s ship-building progress, so perhaps it is not simply an amazing coincidence that the two vessels were completed and launched only a couple of days apart. In any case, news of the Merrimac’s success ran through the telegraph lines, thrilling the South and alarming the North, who feared that the Merrimac would next turn northward to destroy its coastal cities. This was impossible; the Merrimac was clumsy, leaky, and barely seaworthy enough to have made it across Hampton Roads. But the North didn’t know that.

When the Merrimac returned to finish off the last two vessels, it found a small, oddly shaped object—the Monitor—pluckily barring its way. At first the Merrimac’s crew believed the Monitor to be a supply barge, until it fired upon them. Battle between the two ironclads continued for several hours, with each trying to inflict damage upon the other, the Merrimac attempting simultaneously yet unsuccessfully to attack the nearby remaining Northern ships. The Monitor, small, nimble, and quick, protected the ships from further damage, and eventually the Merrimac retired leaking to its port.

Both sides (naturally) declared victory in the battle, but the ultimate outcome was a contract between John Ericsson and the U.S. Navy for a fleet of ironclads, and the successful blockade of the South. The poor Monitor, however, caught in a storm at sea later that year (the Navy still ignoring Ericsson’s instructions on the proper sealing of its turret), went down with sixteen hands off the coast of Cape Hatteras. (Some of her artifacts have since been recovered and conserved.)

Ericsson, who had had a number of professional disappointments, was now vindicated and rewarded, and went on to work in maritime and naval technology and experiment with various sources of power—steam, electric, solar. Three Navy ships have been named after him, and in 1926 the monument pictured above, created by sculptor James Earle Fraser, was dedicated to him. There sits Ericsson (curiously, looking inland rather than out over the Potomac) beneath the Norse World Tree, with Vision standing behind him, flanked by Labor and a Viking warrior. It’s one of your more surprising Washington, DC sculptures. Go have a look.

Although Ericsson regularly sent funds for the support of that son and wife back in Sweden and England, his true passion was engineering, and neither ever joined him in the New World. Thus his days and nights were uninterrupted by the distracting joys and troubles of family life. Ericsson had a reputation for being stubborn, imperious, and single-minded, and perhaps these qualities do not a family man make… but they might enable one to overcome opposition and discouragement and press forward undespairing. Happy Birthday, husband and father of the Monitor.

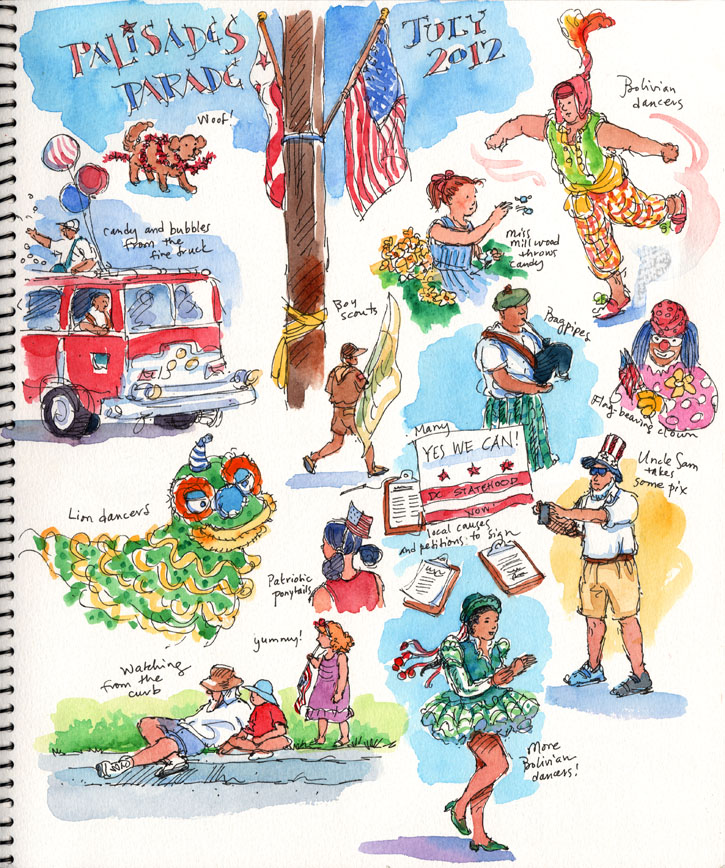

Palisades Parade

Some very quick sketches from one of our family’s favorite Fourth of July activities: the Palisades neighborhood parade. I’m always torn between sketching and just watching.

Given the 100-degree temperatures, we’ll forego that Mall picnic for a swim, read the Declaration of Independence aloud over dinner, and watch the fireworks from the roof. Happy Fourth, everyone!

For sketches from another neighborhood parade (in Montpelier, Vermont), please see Independence Day.

Summer in the South

Today is the birthday of writer Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906), a once-upon-a-time resident of Washington, DC, and the child of former slaves. His father had escaped through the Underground Railroad and fled to Canada, returning to fight in a Massachusetts regiment upon the outbreak of the Civil War; his mother, freed by emancipation and on the verge of emigrating to Liberia, instead decided to remain in the U.S. when the war ended. They met and married post-war in Dayton, Ohio, where Paul was born.

Dayton was a 19th century rural-to-urban destination for southern African-Americans, who quickly established churches, schools, newspapers, and small businesses. Paul’s mother, sure that he showed promise, enrolled herself in night classes (during the day she worked as a cook and laundress) in order to be able to teach her son to read. She encouraged his early interest in writing, and he produced his first poems at age six and began reciting them publicly at nine. In 1887, Ohio abolished racial segregation in the school system (although extracurricular activities like plays and dances remained segregated), and Paul attended local schools as the only African-American student, serving as high school class president and writer and editor for the school paper.

Despite his excellent school record and his having had several pieces of work published in local newspapers, Dunbar found it impossible as an African-American to find either employment in journalism or funds for college. Instead he began working as an elevator operator in the Callahan Building, a seven-story “skyscraper” in downtown Dayton, writing in his spare time. A former teacher’s recommendation acquired him a place reciting his poetry at a convention in Dayton of the Western Association of Writers, and his writing and beautiful voice so impressed the listeners that a nationally distributed write-up of the event brought Dunbar broader attention.

His old school friend Orville Wright, who had dropped out of high school to start a small printing company—having built a press with his brother Wilbur (this in their pre-flight days)—helped Dunbar to self-publish a collection of his poems. Dunbar sold these to his elevator passengers for a dollar apiece, probably hoping that as many as possible would ride all the way to the seventh floor (“While you’re riding with me today, might I interest you in some poetry?”) and eventually recouped his investment. Lucky the buyer with the presence of mind to hang onto that first edition.

Travel and exposure brought Dunbar contacts and supporters, some of them fellow writers. On a visit to Chicago to write about the 1892 Columbian Exhibition, Dunbar met and was befriended by Frederick Douglass. With the patronage of a superintendent of the Toledo State Hospital, Dunbar went on to publish further collections of his work, which were also well-received. Dunbar wrote his poetry both in standard English and in southern dialect, which he had learned through stories from his mother’s Kentucky childhood; the use of dialect in his work has suggested comparisons with Mark Twain.

His growing reputation led to a series of recitals around the U.S. and eventually a six-month recital tour in England, where he also collaborated on theatrical and choral pieces and an operetta. When he returned, it was to Washington, DC and a position at the Library of Congress, meanwhile writing in his free time a collection of short stories and his first novel. The work at the Library was less rewarding than he had hoped, and a whole lot dustier, exacerbating his developing tuberculosis, and with his wife’s encouragement he returned to writing and reciting full-time.

The subject matter for Dunbar’s fiction was drawn from life in black America, and, despite its somber themes, tended to optimistic conclusions. Later criticized for somewhat stereotypical characterizations and a tendency to sentimentality, his writing was unusual in its exploration of the difficulties of African-Americans, both pre- and post-Civil War. In this respect, and particularly in his work in dialect, he influenced later writers of the Harlem Renaissance.

Sadly, Dunbar succumbed to tuberculosis in 1906. During his short life he produced nearly two dozen books: collections of poetry and short stories, novels, and other works. Nevertheless, one can’t help wondering what direction his writing would have taken had he been able to live beyond the age of thirty-three.

Here is one of his poems, “Summer in the South,” and a recently-completed painting to accompany it.

To see where Paul Laurence Dunbar lived and worked in the nation’s capital, you can consult the illustrated Literary Map of Washington, DC.

The oriole sings in the greening grove

As if he were half-way waiting,

The rosebuds peep from their hoods of green,

Timid and hesitating.

The rain comes down in a torrent sweep

And the nights smell warm and piney,

The garden thrives, but the tender shoots

Are yellow-green and tiny.

Then a flash of sun on a waiting hill,

Streams laugh that erst were quiet,

The sky smiles down with a dazzling blue

And the woods run mad with riot.

—Paul Laurence Dunbar

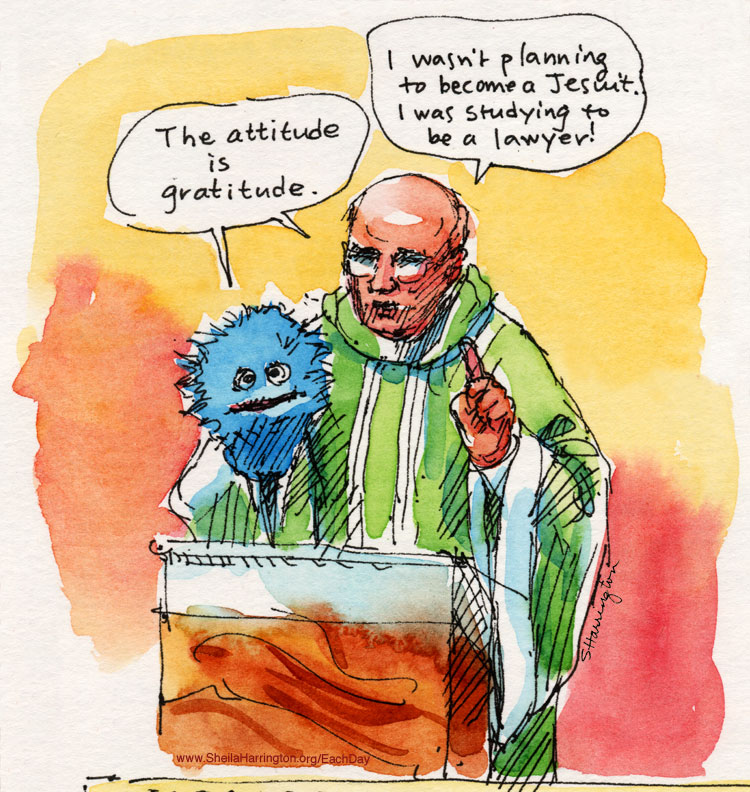

Father of Liturgy, Spirituality and the Arts

One year ago today, Father Larry Madden, probably one of the most beloved priests at our parish church, departed to meet his Maker, taking everyone by surprise. When he didn’t show up to serve at Mass, a search revealed him sitting peacefully in a chair in his room, with a book in his lap. It’s probably one of the top three best ways to depart this earth, but it was a shock for everyone else. At age 78, he was still energetic, youthful, and sharp as a tack.

Father Madden taught theology at Georgetown University and was priest and pastor at nearby Holy Trinity Church during an especially boisterous period of disagreement over [as yet unresolved] issues about the Catholic church’s teachings on women, homosexuality, and liturgical language. With the help of his sense of humor, sensitivity, and wisdom—and perhaps his Jesuit training—he managed to keep conversations going and minds open and moving along the road toward that hoped-for mutual understanding. His homilies (sometimes with the participation of hand-puppet Mr. Blue) were remarkable in conveying messages of multi-level significance that reached listeners of all ages. At Holy Trinity he married hundreds of couples, baptized countless babies, and in times of trouble and joy was both an attentive listener and a thoughtful counselor. He presided at my mother-in-law’s funeral (and, my husband said, “I was hoping he’d be around long enough to do mine.”).

In 1981, Father Madden was chosen to lead the new Georgetown Center for Liturgy, Spirituality and the Arts, established to explore the intersections of these realms. It was an ideal setting for his intense interest in the arts as both a path to and instrument of spirituality. A primary concern of his supervision of renovations of the parish’s aging facilities was in creating the environment to facilitate such connections. As a parishioner I can testify that his after-Mass Adult Ed lectures on symbol and ritual were passionate and profound (at Woodstock College he was co-creator of the documentary film “Ritual Makers”), yet his fascinating observations were inevitably interspersed with funny good old Irish storytelling.

And besides all this, he sailed (including a race from California to Hawaii), sang with enthusiasm, and played piano (once, so the story goes, with Tony Bennett). I can’t sing “Lights of the City” without hearing Larry Madden’s Irish tenor leading the congregation.

Now he’s playing piano for the angels. How we miss him.

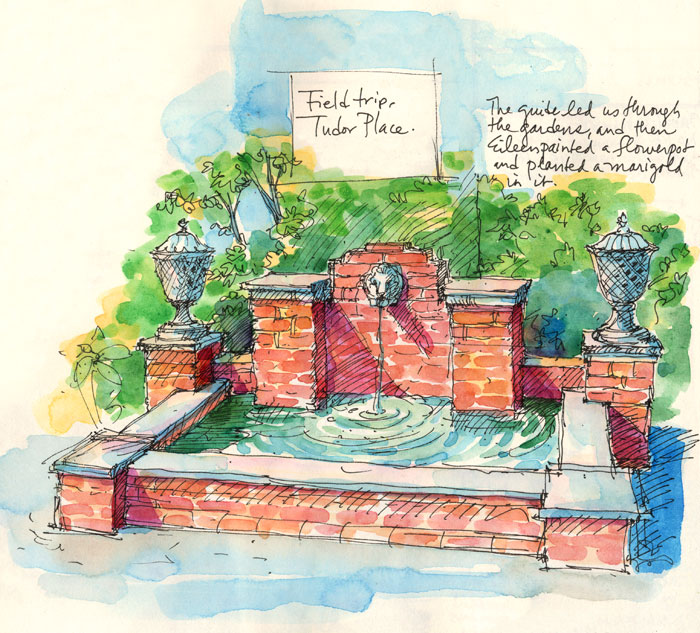

A Field Trip for Moms

If you have not yet visited Tudor Place in Washington, DC, and the mothers in your life (perhaps including yourself) are fans of garden walks/historic houses/afternoon tea, you may want to add it to your Expeditions list. Built in 1816 by Martha Washington’s granddaughter, Tudor Place sits on, unbelievably, five (5!) acres in the middle of Georgetown, and is a green, flowery and bird-filled retreat from the busy surrounding streets.

I post this sketch today because Tudor Place was one of our three-generation (grandmother-mother-daughter) destinations when my mother was still with us, and every visit is a lovely, though poignant, reminder. Happy Mothers Day, Mom, and all you mothers out there. May your day hold flowers and bird-song.