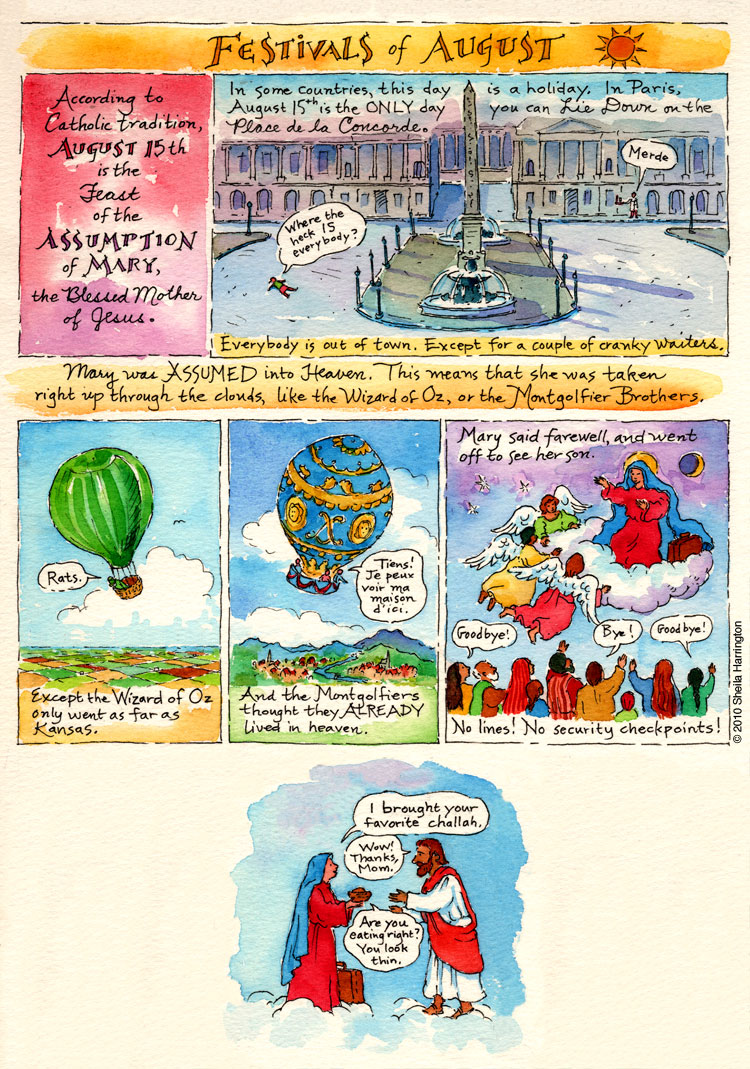

Category: Illustration

Look Before You Leap

Mountain Woman Part 1

Imagine that you are a little girl born in a village in North America in the early 19th century. You, like the other village girls and their mothers, help maintain a family farm: growing vegetables, cooking, scrubbing, making clothes. You might see your destiny as a farmer’s wife, raising children to follow in your footsteps.

But perhaps your mother is also an advocate for women’s suffrage, and your father is a fierce abolitionist, which might give you a somewhat different perspective on your life. This was the parentage of Julia Archibald (1838-1887), later Julia Archibald Holmes, born in the village of Noël, Nova Scotia, in 1838. And today, August 5th, is the anniversary of the day she became the first woman to reach the top of Pikes Peak, Colorado, when she was twenty years old.

When Julia was about ten, the family moved to Worcester, Massachusetts (where her mother became friends with Susan B. Anthony). But they didn’t stay there long. Slavery had been abolished in Canada in 1834, but there was a growing anti-slavery movement in the United States, and Kansas was the place in which the Archibalds decided to support it. They had a mission.

A series of treaties had declared Kansas to be Indian Territory, and a number of Native American tribes had been removed from their eastern lands and resettled there. Nevertheless, increasing numbers of westward-bound pioneers followed trails that passed through the territory, and by 1850 settlers were squatting along the trails and elsewhere in Kansas. Pressure from these land-hungry folks led eventually to (familiar story) the creation of new treaties, the removal of tribes to areas yet further west, and the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, opening the area officially to settlement.

It was not only Native American tribes who were unhappy about this. Slave-state Southerners were displeased that the decision about the existence of slavery in the new territory was to be left to its residents. So, as you might guess, both advocates and opponents of slavery rushed into Kansas, each staking out territory and hastily setting up local provisional governments and institutions that were attacked by both sides, setting off several years of violence that foreshadowed the Civil War.

The Archibalds settled in Lawrence, Kansas, a center of controversy, and their house became a way station on the Underground Railroad. In Lawrence Julia met James Holmes, a veteran of John Brown’s campaigns. Apparently he was fiery and dedicated; she was handsome and spirited; there were certainly similarities of background. They were married in 1857.

But they didn’t stick around in Kansas for the resolution of the national conflict. The following year they joined a wagon train headed for Colorado, where gold had been discovered. And a lot of other excited Kansans were doing the same thing. Not many gold-seekers actually found what they sought, but their immigration resulted in the founding in Colorado of towns, businesses, churches, and probably plenty of saloons, as well as a rapid dramatic increase in its population.

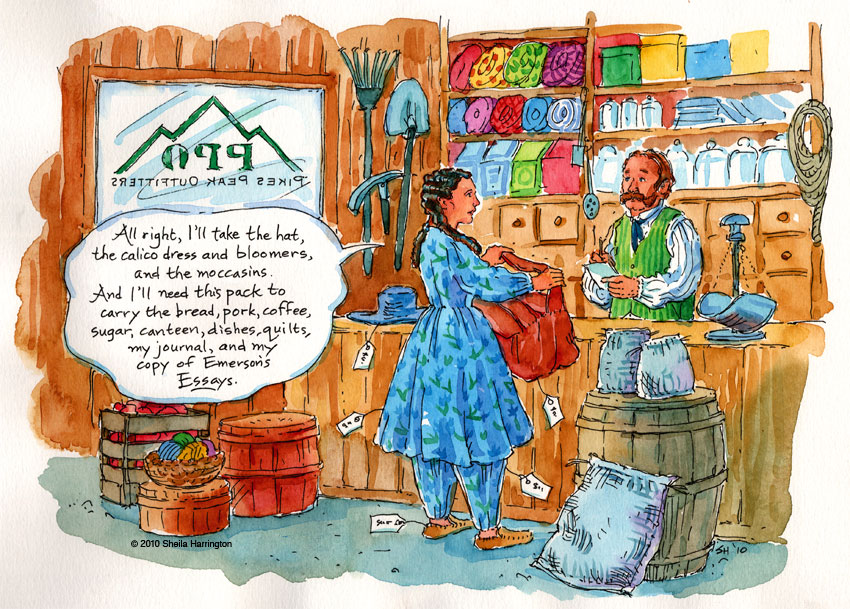

According to Julia’s journal, their own party was driven more by “a desire to cross the plains and behold the great mountain chain of Noth America” than to search for gold. She acquired what she deemed a sensible traveling outfit: hat, moccasins, short calico dress, and bloomers. Bloomers had been recently introduced to the public by women’s suffragists as more sensible than skirts.

Her choice of clothing gave Julia the freedom to walk beside the covered wagons instead of riding. She improved her stamina by deliberately increasing her daily distance, and she recorded her observations of wildflowers, landscape, and skies in her journal. The only other woman on the trip disapproved of Julia’s unconventional garb and stayed in her wagon, thus missing most of the scenery. (Like my children, with noses in their books when we travel. “Look! Look out the window!”)

To Be Continued—Please see August 6/Mountain Woman Part 2

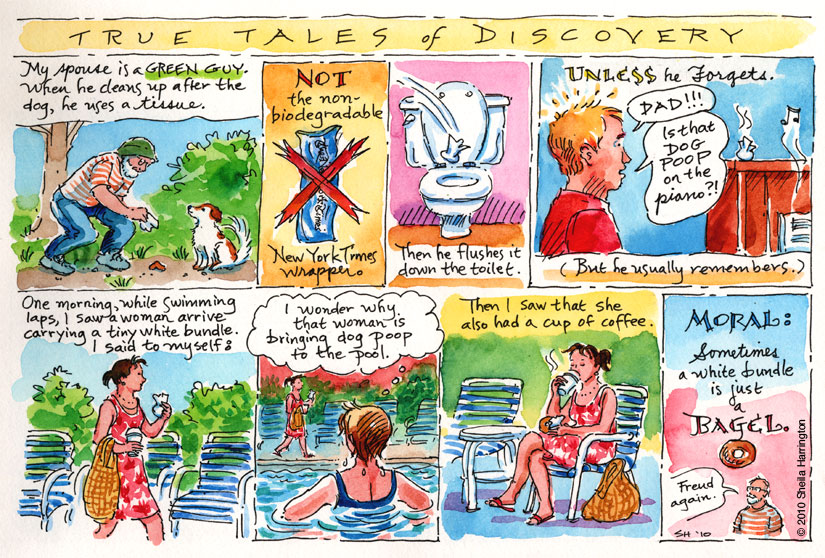

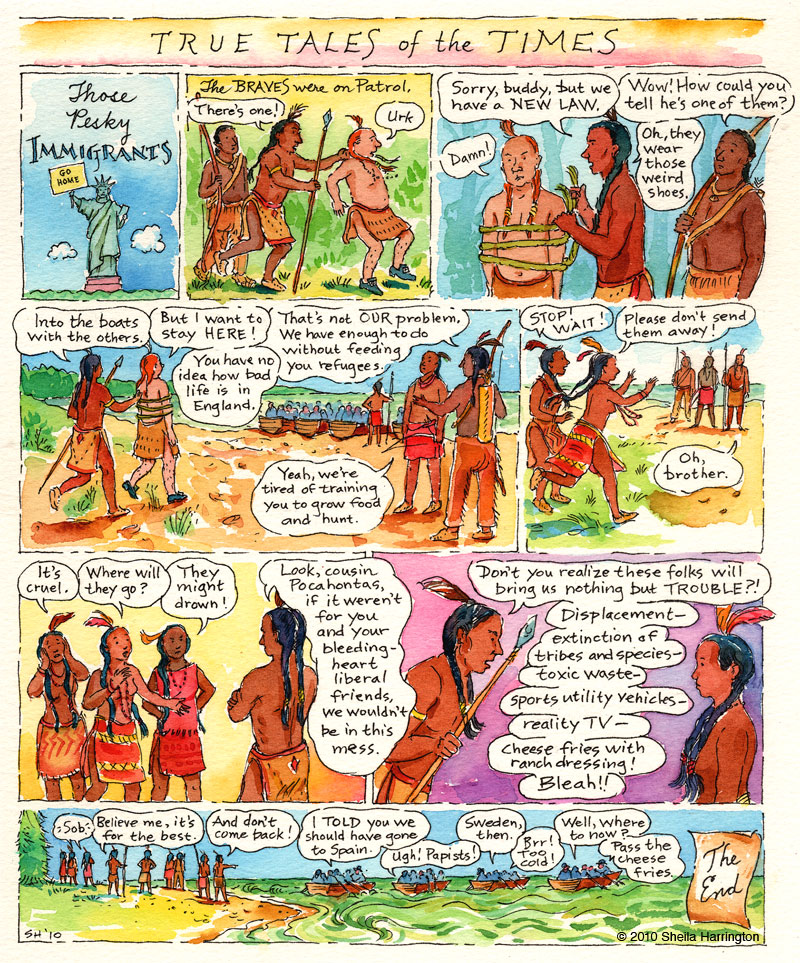

Illegal Immigration

This cartoon is bizarrely appropriate for today, because it is the birthday of the sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi (1834-1904), whose most famous work, Liberty Enlightening the World, is known to us as the Statue of Liberty. I plan a lengthier post about him in 2011. Thank you and Happy Birthday, Frédéric. May your sculpture continue her courageous task of enlightenment.

Below: Illegal immigration is an issue that apparently remains unresolved in Virginia. And elsewhere.

Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night…

Today is the anniversary of the day in 1775 that Benjamin Franklin was appointed First Postmaster by the Continental Congress of the thirteen colonies. If you do not already know the history of the United States Post Office from the trial scene in the movie Miracle on 34th Street (the fabulous original 1947 version, not the flimsy imitation made in 1994), read on.

This method (above) of delivering mail no longer exists in the United States, except in remote outposts of Delaware, where descendants of 17th-century Swedish settlers cling to time-honored traditions.

Message delivery services have been around for thousands of years. The ancient Chinese had one, as did the Mayans, and the Aztecs. The efficient postal system of Persia inspired Herodotus to write in the 5th century B.C., “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” Except he said it in ancient Greek.

When English colonists arrived on these shores in the 1600s, they were probably familiar with the recently developed London Penny Post. Send a letter anywhere in London for a penny! or elsewhere for additional fees (seems rather expensive given the era, though). The cost could be paid by either party, which occasionally discouraged someone from picking up a delivery. (“Who, me? Must be some other Frederick Forecastle.”)

In the New World, letters were delivered by any available means. They might be entrusted to a friend or family member going in the same general direction as the letter. They were carried by traveling merchants, ships’ captains, local Native American tribal members, or servants or slaves running errands—in other words, pretty much anyone who was on the road and headed in the general direction of one’s addressee. If they couldn’t be hand-delivered, they were often left at the closest tavern, to be picked up by a visitor who might know the recipient.

The first “official” post office was Fairbanks’ Tavern in Boston, named in 1639 by the British Crown as a collection site for mail between the colonies and England. William Penn set up a service for Pennsylvania in 1692. By the 1700s, several other locations had been designated throughout the colonies, as well as postal carriers who delivered mail among them. Roads were few, and pretty terrible. Some were existing American Indian trails. (The monthly post rider’s trail between New York and Boston, the Old Boston Post Road, is part of today’s U.S. Route 1.) People didn’t receive mail often, but it’s surprising that so many letters made it.

In 1737, Benjamin Franklin was named postmaster of Philadelphia by the British Crown, and in 1753 one of two postmasters-general for the colonies. As you might imagine, Franklin jumped in and made improvements, setting out on a post office inspection tour, surveying and shortening routes, and installing milestones. He also established a penny-post, streamlined accounting methods, and instituted night riders. The Crown dismissed Franklin in 1774, however, for his ornery revolutionary ideas. By that time, the postal service was operating from Maine to Florida and New York to Canada, on a regular schedule, and for the first time was making a profit. (The British government ought to have known they were in for trouble.)

As early as 1775, postal carriers operating under the Continental Congress were hired as persons of good reputation, sworn to lock and secure the mail they carried (which might sometimes have included inflammatory anti-British sentiments). After the war, the Continental Congress re-hired Franklin, making him the first official Postmaster General of the new United States.

The development of the Postal Service has followed that of the nation, expanding in area served as new states were added. Mail has been carried by horseman, stagecoach, railroad, steamboat, truck, and pneumatic tube. (My mother, who grew up on a sheep ranch in Mendocino County, California, had the responsibility of going to “meet the stage” and fetch the family mail. Although it was by that time a truck, the family still automatically called it “the stage” because in her grandparents’ day it had been a horse-drawn stagecoach.) In 1918 the first airmail routes were established. How exciting, to receive mail that had actually FLOWN in an AIRPLANE, which very few citizens had ever experienced themselves.

Today I can email messages and photos to family and friends living across the country and on other continents, and hear back from them within seconds. When our son studied abroad in Japan, we could sit in front of our respective screens and unwrap our Christmas presents together. This definitely has an Amazement Factor. However, praiseworthy though it may be, these are only ELECTRONIC IMPULSES and PIXELS, folks.

Picture this: your friend, who lives on the other side of the world, wraps a lovely gift and attaches a heartfelt handwritten note decorated with little stars and hearts. He/she (probably a she) takes it to the local post office, and in a few days your Friendly Neighborhood Postal Carrier, who trudges faithfully to your home day after day, year after year, through snow, rain, heat, and all the aforementioned, delivers it Personally into your Hands. Along with heaps of other real stuff too, like offers for credit cards, and Victoria’s Secret catalogues. Wow! Now that is what I call amazing. Think of this, and remember your postal carrier at the holidays. And take a moment to smile and thank your postal carrier, today and every day.

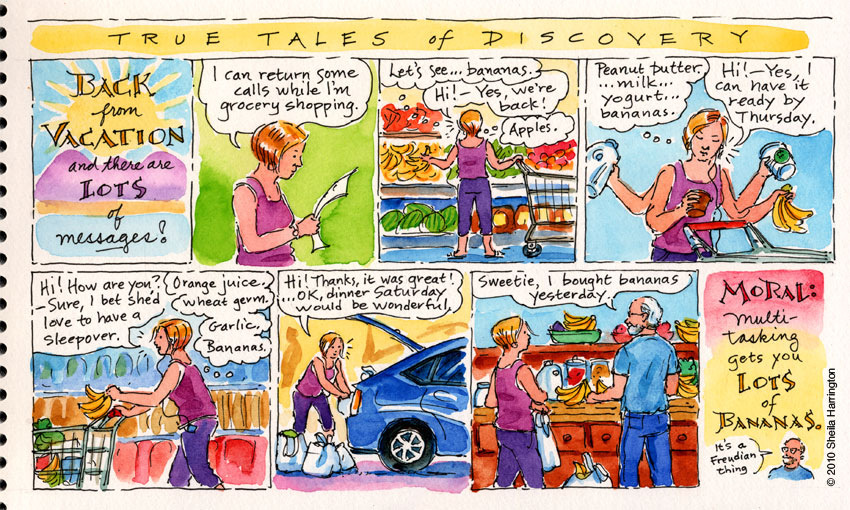

Bananas

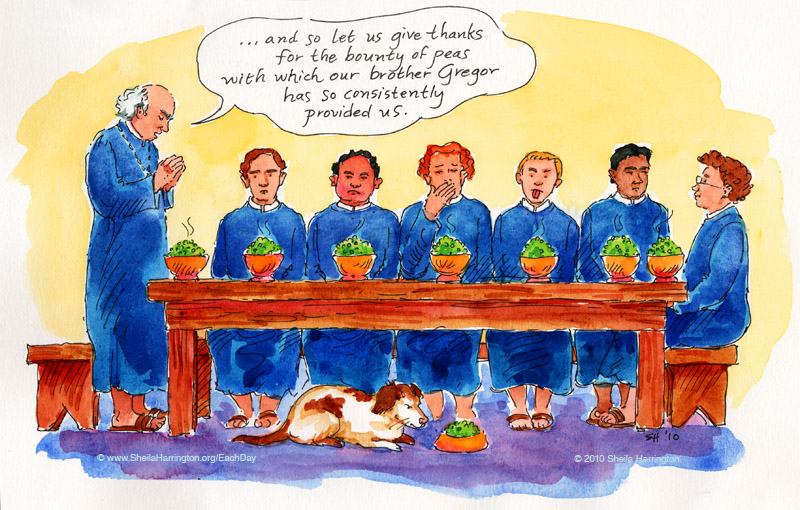

Peas of Mind Part I

When I was in 8th grade, I had a crush on Gregor Mendel. No, he was not a Czechoslovakian exchange student. He was a 19th-century scientist whose birthday it is today. And what red-blooded schoolgirl would not fall for a man who was fascinated with plant and animal heredity and grew thousands of peas to test a hypothesis, thereby becoming the father of modern genetics? (Well, probably there are a few. But it’s a pattern: in third grade my admiring glances fell upon the boy who won all the class math competitions; and my hubby, a man of diverse talents like sculpture, electrical wiring, and the infant football-carry, is also no slouch in the brains department.)

Gregor Johann Mendel (1822-1884) was born into a farming family in the tiny village of Heinzendorf in what was then the Austrian empire and is now the Czech Republic. A bright boy, curious about the many growing things he observed in his rural world, he quickly outgrew the village grammar school. His parents, though not well-off, paid what they could for him to attend school in the next town—which was tuition plus only half his meals, so Gregor often went hungry.

Funding ended abruptly when Mendel was 16 and a back injury prevented his father from farming. Although he always helped with the farm work, Mendel, the only son, was more interested in studying plants and sheep than in raising them. So eventually the farm was sold to provide for living expenses and daughters’ dowries. Mendel took on tutoring work to continue paying for classes and books. And Mendel’s younger sister used her dowry to help her big brother finish high school. Now THAT is a loving sister.

But university education couldn’t be paid for with tutoring. One teacher suggested a solution: if Mendel didn’t mind giving up the possibility of marriage and family, he could enter an abbey. Friars followed a range of paths. They didn’t spend all their time praying and preaching—they were farmers, beekeepers, bakers, teachers, mathematicians, philosophers, scientists. For centuries this had been the road to education for many bright but poor boys (undoubtedly many of them without a genuine vocation).

So Mendel entered the Augustinian Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno, known for its intellectual pursuits and its enormous library, to continue his education. The abbot, recognizing Mendel’s gifts, sent him on to the University of Vienna to study with leading scientists (one of them Christian Doppler, of Doppler effect fame). When he returned, he taught science at the monastery-run high school, for which he apparently had a natural gift, teaching with refreshing clarity and humor. At the same time he continued his own studies in astronomy, meteorology, zoology, and botany.

Interested in the mysteries of heredity since his farming childhood, he wished to investigate its laws. He began breeding mice of different colors to study the pattern of color inheritance, but the bishop thought the study of mouse-breeding was messy and unsuitable for a monk. So Mendel switched to garden peas, which are better-smelling and less shocking in their reproductive habits (although the subject of plant reproduction had certainly shocked the colleagues of Carolus Linnaeus in the previous century).

Mendel received a garden plot in the monastery’s botanical garden and began to experiment with thirty-four varieties of peas: tall, short, yellow, green, wrinkled, smooth, white blossoms, purple blossoms, grey seed, white seed. His goal was to determine what principles governed heredity. Clearly offspring shared some traits with their parents—but which ones, and why? How were characteristics passed from one generation to the next?

TO BE CONTINUED! See July 21st.

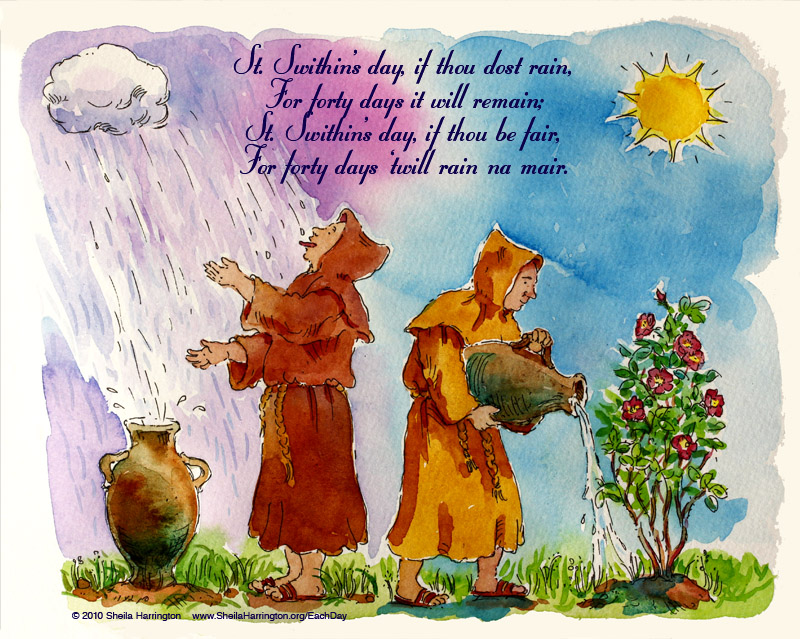

Rain or Shine?

Look out the window. Doth it rain today, or doth it shine? Prepare yourself. Today is the feast day of St. Swithin, and for the next forty days you can plan your activities and wardrobe according to the old verse.

Swithin was born in the 9th century—the precise year is unknown—in Winchester, England, during the reign of King Egbert of Wessex, who ruled from 802 to 839. There are but a few reliable facts of his life, drawn from church records. Nevertheless, there must have been something about the fellow, for, both during his life and afterward, he inspired numerous stories and customs that have endured for the last twelve centuries.

Swithin was ordained as a monk and gained such a favorable reputation that he was selected as a tutor to Egbert’s son Aethelwulf. When Aethelwulf himself became king, he appointed his former tutor as bishop of Winchester, where for the next ten years Swithin built numerous churches as well as the town’s first stone bridge. Nevertheless he apparently remained a modest, unassuming fellow, charitable and sensible, preferring to go about on foot, avoiding ostentation. He also managed to convince Aethelwulf to donate a tenth of his own lands to pay for some of the church-building. Swithin’s dying request was to be buried not indoors within an elaborate shrine, as was customary with prominent folk, but outside in a simple churchyard grave, where “the rain may fall upon me, and the footsteps of passers-by.” When he died in 862, his request was granted…for a while.

But a hundred years later, when the bishops of Canterbury and Winchester were renovating the church and undertaking reforms, they cast about for relics of a saintly candidate to inspire their parishioners. Swithin had the fortune, or misfortune, to be associated with numerous miracles both before and after his death, among them the healing of ailments of the eyes and the spine, and the kindly repair of an elderly woman’s broken eggs so that they were good as new, a miracle that would certainly come in handy in any household. What luck to find a local guy that no one had yet claimed! The two bishops decided to elevate unpresumptuous St. Swithin to more prominent status. What better way than to remove his body from its humble grassy setting and place it in a more visible shrine within the newly renovated church?

Well, as the story goes, when they set about digging up Swithin, the sky clouded over, and a heavy rain began that continued for the aforementioned forty days. This would certainly indicate heavenly displeasure, if one were inclined to interpret such signs. But it did not deter the church authorities, who persisted in their plan and not only dug up St. Swithin’s body but sent his head to Canterbury Cathedral and his arm to Peterborough Abbey, rather than selfishly keep the entire saint in Winchester. They also rededicated the church (formerly dedicated to St. Peter and St. Paul). At some point along the way Swithin acquired the title of “Saint,” although he was never formally canonized by the church. He is what is known as a “home-made saint,” and churches all over the British Isles are named after him.

However, despite—or perhaps because of—all this unsolicited attention, St. Swithin still has his say every July 15th, determining the weather for the following month or so. According to a study conducted in Great Britain in the last decades of the 20th century, around mid-July the weather tends to settle into a pattern that lasts until late August, and this is true for about seven out of ten years. It either has something to do with the jet stream, or with Swithin’s periodic annoyance at being kept indoors. When it rains in August, the saying goes, “St. Swithin is christening the apples.”

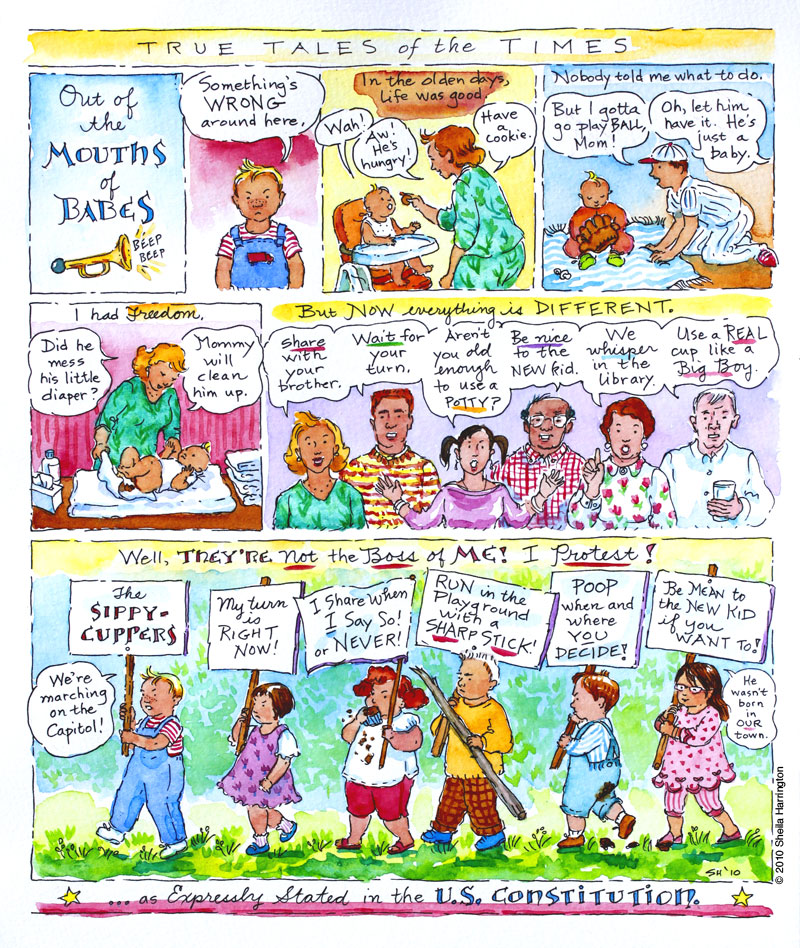

Li’l Patriots

Dying Clean

Years ago, when I worked full time, and we were all preparing to head out of town for our annual convention, one of my colleagues always announced, “I’ve got to go home and get my house dying clean.” I didn’t really believe that her grieving family’s first thoughts would be for the impeccable cleanliness of her home. Ah, how simple my life was then. With time, I too have become an initiate of the pre-travel cleaning blitz. Not because I worry about the state of my house after my death. But because I don’t want to walk in the door to find heaps of laundry and dirty dishes when I return home with a car full of wet bathing suits and cracker crumbs.