(Continued from Peas of Mind Part I, July 20)

Speculation on this subject probably dates from prehistory, when nomadic peoples discovered that fallen seed produced new grain, and that it was handier to domesticate sheep than to chase after them in the wild. Selective breeding of plants and animals is thousands of years old.

But how did it all work? Why did sheep vary in color, size, and wool quality? For that matter, why did sheep give birth to lambs instead of, say, lentils? Was it all an unchanging predetermined system, set in motion by a Creator? Was variation due to inner mechanisms, or to external factors, like environmental requirements, or supernatural forces? Did new species generate spontaneously, from water, mud, cheese, and old rags? Was there an underlying material explanation for the workings of the Great Chain of Being?

Every people has had its explanation for the workings of existence. From mythology to religion to philosophy, theories abound. And as the world has shrunk and human consciousness evolves, explanations are increasingly shared, expanded, and abandoned.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, the Western world was seized with a new fever of questioning in all areas of natural science. By the 19th, scientists working independently in diverse fields were moving inexorably from childlike faith in mythology and magic toward a secular, observation-based, material Explanation For Everything. It was the early adolescence of Western thought: Ha! You don’t know everything, God, so I’m going to search for the truth myself! And maybe I’ll find out you’re not even there! Questioners sought to discover universal underlying principles of existence, revealing that they retained a desire for Oneness through science that would replace loss of faith. But that’s another post…

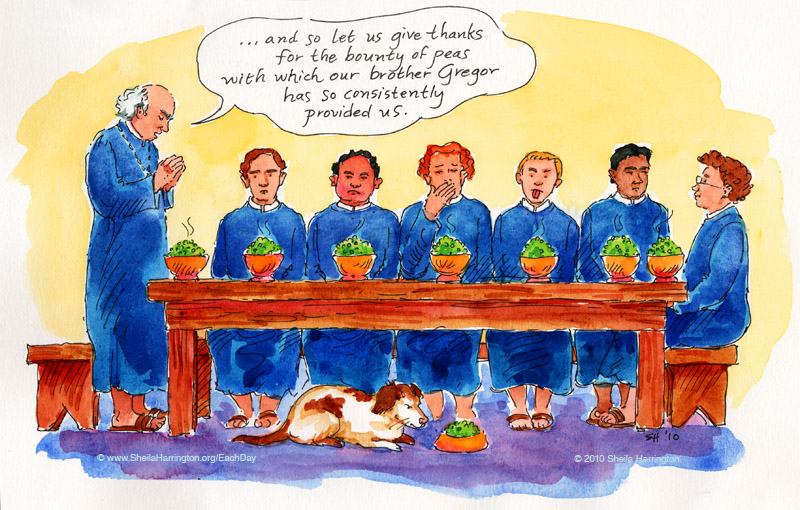

So back to Mendel and his peas. (I realize this is my SECOND post about a monk this month! but that is pure coincidence.)

Pea plants are self-pollinating, but Mendel controlled pollination by removing stamens from selected plants and pollinating specific generations by hand, controlling for one characteristic at a time and keeping detailed mathematical records of the results. His experiments revealed consistently that, although the offspring of a first generation of peas always resembled the parents, the offspring of two crossed generations resembled only ONE parent—and, most surprising, that among the offspring of the hybrids, three out of four peas displayed one parental trait and the fourth pea displayed the other.

Other scientists had previously studied cross-pollination, but without coming to final conclusions or developing laws of inheritance. But Mendel, after growing thirty thousand plants over eight years, deduced the existence of what he called dominant and recessive traits, controlled by elements within the egg cell and the pollen of plants (later called genes). He also concluded that each parent carries half the elements passed on to offspring, and that these individual elements remain present and distinct, controlling specific characteristics like eye and hair color. (We’re no longer talking about peas here, except for unusual, Pixar-type peas.) This was in contrast to others, including Charles Darwin, who thought that characteristics from parents blended within the offspring.

In 1865 Mendel presented his findings to the Natural Sciences Society of Brünn, and later mailed printed copies throughout the scientific community (Darwin got one), but he received little response. Some fellow scientists were confused by his mathematical approach and his talk of distinct inherited traits. And what did peas have to do with people? Mendel was disappointed, but shortly thereafter he was elected abbot of the monastery, and although he continued gardening and beekeeping, his duties left no time for further experimentation. His position, however, now made possible financial assistance for his sister’s children (and a fire house for his home village).

Upon Mendel’s death, his successor burned his papers. (Horrors! I bet there’s a secret story in that.) Fortunately, the papers Mendel had mailed abroad survived. But it wasn’t until the early 1900s that his work was rediscovered by several scientists working independently of one another in Holland, Germany, England, and the United States, taking them by surprise. His work was challenged and his theories modified, but he had grasped certain basic principles of heredity fifty years ahead of anyone else, and terminology was developed for the field of study Mendel had initiated and the mechanisms and processes he had described.

Even though middle school was a LONG time ago, I cannot see peas in a garden without thinking of dear Gregor. Sigh. Including these delicious sugar-snaps growing in our friend Susan’s Vermont garden, which my daughter and I sketched for our Botany block. We picked and ate plenty of them, too. That was for our Gastronomy block.