If you lived in 17th century England and were found guilty of stealing, consequences could be severe: whipping, branding, a term in the pillory, even hanging. An alternative was transportation to the New World and seven years of indentured servitude. The colonies needed laborers.

For some people what was essentially permanent exile might have seemed worse than hanging. But it apparently worked out well for one Molly Welsh, a dairymaid who was transported and indentured to a Maryland tobacco planter in 1683 when she was found guilty of stealing, or at least knocking over, a pail of milk. It was a life-changing accident. After working a seven-year term, Molly had earned enough to buy a tobacco farm of her own, and bought a slave named Banneka (or Banneky) to help work it. Although interracial marriage was illegal at the time, love triumphed. Molly freed Banneka; the two were married and had four daughters.

One of their daughters also fell in love with a slave, so her parents bought his freedom to enable them to marry. Because like many slaves he had no surname, when they married he took their name (now Banneker) as well. And these were the parents of Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806), whose birthday it is today.

Benjamin was from all accounts a very bright child. His grandmother Molly taught him to read and write, and he was eager to learn from any available source. But books were few. Around 1770, three Ellicott brothers from a large Pennsylvania Quaker family built a mill, homes, and store nearby, which eventually became the hub of a prosperous community (now Ellicott City). The Ellicotts and their offspring were mechanically inclined and enjoyed experimenting with mechanical and scientific inventions. The family befriended their knowledge-hungry neighbor Benjamin and lent him books, tools, and a telescope.

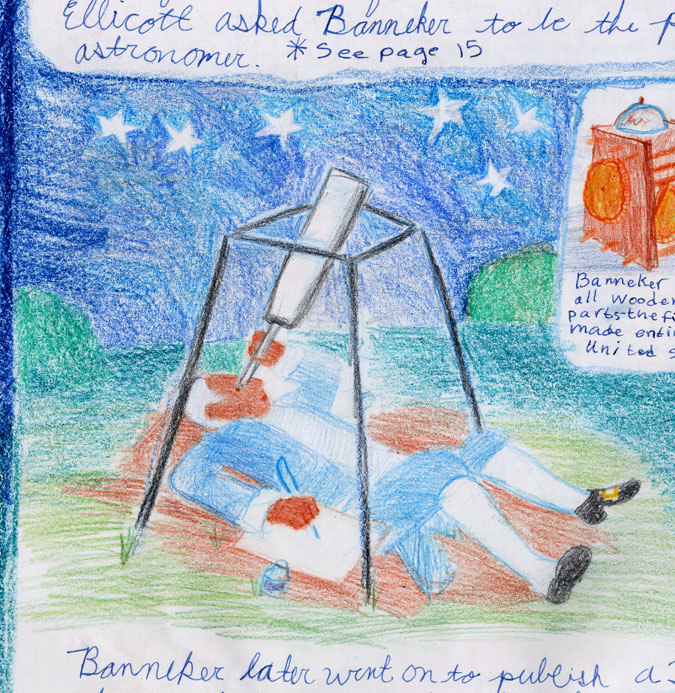

From that moment Banneker was devoted to astronomy, which he taught himself from the books and from studies of the night sky he made (in addition to carrying on the work of the family farm). He became so skilled that in 1791, when Andrew Ellicott, who had helped complete the Mason-Dixon Line survey, was hired to survey the land for the nation’s new capital city, he asked Benjamin Banneker to help him with the necessary astronomical observations. It’s pretty rough spending your nights outdoors for months stretched out on the cold ground measuring the stars when you’re 59 years old, but Banneker agreed. (This is the scene depicted above in my daughter’s Main Lesson book from our homeschooling Local History and Geography block.) So off they went to lay out the boundaries for the ten-by-ten-mile square that was to become Washington, DC. Some of the original boundary stones are still visible.

In the course of this project Banneker grew ill and was obliged to retire to the farm. But he was undeterred from his studies, and by 1792 he had created and published an almanac that included forecasts of weather, tides, eclipses and other movements of heavenly bodies—all calculated by Banneker—as well as festival days, essays and poetry (including work by Phillis Wheatley), instructions for home medical care, and Banneker’s views on free public education and religion.

The almanac was distributed in four states and went through several editions, one of which included an exchange of correspondence between Banneker and Thomas Jefferson, then serving as Secretary of State under George Washington. Banneker pointed out in his letter the irony of Jefferson’s having stated in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal” while simultaneously “detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren, under groaning captivity and cruel oppression.” In Jefferson’s polite and complimentary response, however, he avoids addressing this conundrum in his life, as he adroitly managed to do whenever it was mentioned.

Abolitionists in the colonies and Great Britain were thrilled with the almanac as another piece of evidence for the immorality—in fact, the downright senselessness—of slavery. Happy Birthday, Benjamin Banneker. Your work is another milestone on the road to freedom.

Sheila – Last night I went out with binoculars to look at the moons of Jupiter for the first time in 10 years. Always a thrill to see them. The web site below tells you where to look for the moons at any given time. They move quite quickly so even a couple of hours gives a different pattern.

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/observing/objects/javascript/3307071.html#

David