Today is the birthday of Jana, the kind of person everyone ought to have for a friend and neighbor. Yet she remains genuinely unimpressed by her contributions to the world around her. Happy Birthday, dear Jana! Guess what’s in the bag.

Tag: Birthday

The Sunlight on the Garden

As we approach the end of summer, a rather melancholy poem, on the birthday of its author John MacNeice (1907-1963). By way of contrast, a watercolor of sunny wood poppies, which bloom most satisfactorily all season long and sprinkle their seed generously every year, ensuring a steady supply of offspring. Painted for sunny and generous Colette.

The sunlight on the garden

Hardens and grows cold,

We cannot cage the minute

Within its nets of gold;

When all is told

We cannot beg for pardon.

Our freedom as free lances

Advances towards its end;

The earth compels, upon it

Sonnets and birds descend;

And soon, my friend,

We shall have no time for dances.

The sky was good for flying

Defying the church bells

And every evil iron

Siren and what it tells:

The earth compels,

We are dying, Egypt, dying

And not expecting pardon,

Hardened in heart anew,

But glad to have sat under

Thunder and rain with you,

And grateful too

For sunlight on the garden.

—Louis Macneice

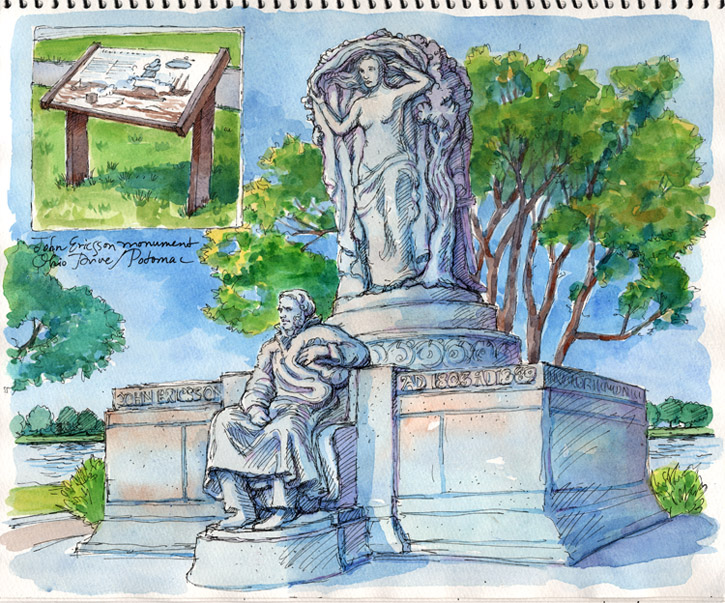

Father of the Monitor

Where in Washington, DC—a city not known for its ancient fanciful mythology, except of the political kind—can you find an outdoor sculpture of Yggdrasil, the World Tree of Norse legend?

If you are zipping along in a car, you’ll miss it. But if you are traveling by foot or bicycle, you can take a break on a small green island (which I discovered by accident on a family bike ride, and returned to sketch) at the intersection of Ohio Drive and Independence Avenue, along the Potomac River. There at the foot of Yggdrasil sits John Ericsson (1803-1889), whose birthday it is today.

Ericsson, born in a Swedish village and son of a mining engineer, was a precocious child who demonstrated early an aptitude for all things mechanical. At five he created a working windmill from clock parts and household utensils. There is no historical record of his mother’s reaction to the missing tableware. At eight his education included informal instruction from his father’s engineering colleagues, and eventually he joined the team (although still too small to reach all the equipment), drawing up plans and supervising crews. During a period in the army he worked on designs for steam and fume-propelled engines, but finding no funding he took himself to England (leaving behind an out-of-wedlock son to be raised by his mother), which was then the hub of the Industrial Revolution and a showcase for new canals, railways, factories, and every sort of engine and mechanical device.

But despite his innovations in locomotive and marine engine designs, and his best-known creation, the screw propellor—which rendered vessels far more efficient and whose descendants are still in use worldwide—the English were unresponsive, perhaps because of Ericsson’s reputedly uncompromising nature, or perhaps because of his foreign origins. So Ericsson (leaving behind an English wife) betook himself to the young United States, with its energetic, ambitious entrepreneurs, and settled in New York, where pretty much everyone had (as today) foreign origins.

Here Ericsson sought supporters within the Navy and private industry for his screw-propellor vessel designs. He also tried, unsuccessfully, to interest the French Emperor, then engaged in the Crimean War, in a new rather peculiar-looking design for an iron-clad vessel (iron-clad ships having shown their effectiveness against the traditional wooden model).

But it was the American Civil War that delivered his opportunity. When the Southern states seceded from the Union in 1861, taking with them the Navy Yard at Norfolk and the USS Merrimac, which the Confederacy began to sheath with iron, it became obvious that the U.S. needed its own ironclad ship to protect the Northern coastal blockade. Ericsson’s industrial business contacts, who saw war as a terrific opportunity to increase their fortunes patriotically, used their influence within Congress and the U.S. Navy to advocate the implementation of Ericsson’s ingenious design, negotiate a contract, and launch construction of a vessel, in an unbelievably short period.

Ericsson’s ironclad ship (named the Monitor by Ericsson, as it was intended to monitor the coastline), with its iron sheath extending below the water line, its revolving turret that permitted it to fire in all directions, and its screw propellor, kept iron works, foundries, rolling mills, and manufacturers busily employed for months. For the sake of speed, some of its innovations (such as the underwater torpedo) were set aside, to be adopted later. Some were ignored, to the ship’s peril, as we will see.

Because the strange new vessel was untested, its crew was composed primarily of volunteers. Some observers (untutored in the laws of physics) predicted she would sink instantly when launched on March 6, 1862, headed for Norfolk. However, although the Monitor endured rough weather (and leaks, due to the Navy’s having ignored Ericsson’s instructions for the turret’s sealing), she arrived safely in Hampton Roads on March 8th, to find disaster: two ships already destroyed by the Confederacy’s Merrimac, and two others run aground awaiting their own coups de grâce.

For, during the past few months, the Confederacy had been hurriedly adapting the Merrimac (which they renamed the Virginia), preparing it to ram and sink the Yankee ships at Hampton Roads, to break the blockade and enable the resumption of Southern trade. Because the Union and the Confederacy were both riddled with spies, each knew something of the other’s ship-building progress, so perhaps it is not simply an amazing coincidence that the two vessels were completed and launched only a couple of days apart. In any case, news of the Merrimac’s success ran through the telegraph lines, thrilling the South and alarming the North, who feared that the Merrimac would next turn northward to destroy its coastal cities. This was impossible; the Merrimac was clumsy, leaky, and barely seaworthy enough to have made it across Hampton Roads. But the North didn’t know that.

When the Merrimac returned to finish off the last two vessels, it found a small, oddly shaped object—the Monitor—pluckily barring its way. At first the Merrimac’s crew believed the Monitor to be a supply barge, until it fired upon them. Battle between the two ironclads continued for several hours, with each trying to inflict damage upon the other, the Merrimac attempting simultaneously yet unsuccessfully to attack the nearby remaining Northern ships. The Monitor, small, nimble, and quick, protected the ships from further damage, and eventually the Merrimac retired leaking to its port.

Both sides (naturally) declared victory in the battle, but the ultimate outcome was a contract between John Ericsson and the U.S. Navy for a fleet of ironclads, and the successful blockade of the South. The poor Monitor, however, caught in a storm at sea later that year (the Navy still ignoring Ericsson’s instructions on the proper sealing of its turret), went down with sixteen hands off the coast of Cape Hatteras. (Some of her artifacts have since been recovered and conserved.)

Ericsson, who had had a number of professional disappointments, was now vindicated and rewarded, and went on to work in maritime and naval technology and experiment with various sources of power—steam, electric, solar. Three Navy ships have been named after him, and in 1926 the monument pictured above, created by sculptor James Earle Fraser, was dedicated to him. There sits Ericsson (curiously, looking inland rather than out over the Potomac) beneath the Norse World Tree, with Vision standing behind him, flanked by Labor and a Viking warrior. It’s one of your more surprising Washington, DC sculptures. Go have a look.

Although Ericsson regularly sent funds for the support of that son and wife back in Sweden and England, his true passion was engineering, and neither ever joined him in the New World. Thus his days and nights were uninterrupted by the distracting joys and troubles of family life. Ericsson had a reputation for being stubborn, imperious, and single-minded, and perhaps these qualities do not a family man make… but they might enable one to overcome opposition and discouragement and press forward undespairing. Happy Birthday, husband and father of the Monitor.

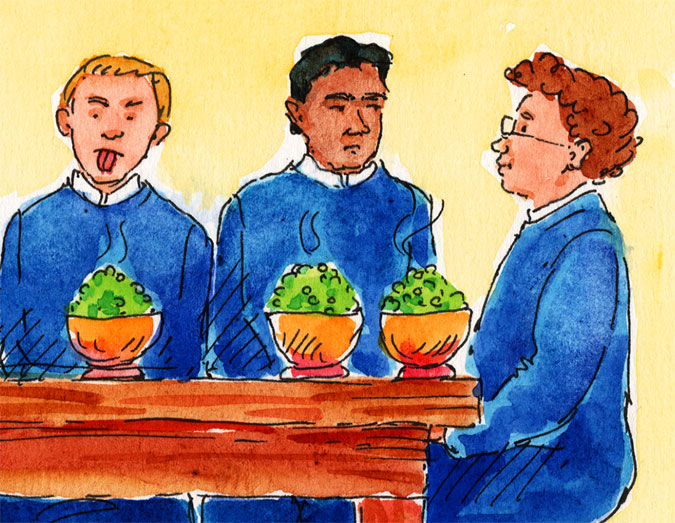

Please Pass the Peas

Have a big bowl of peas to celebrate the birthday of scientist Gregor Mendel (1822-1884). For his story, and pictures, please see Peas of Mind.

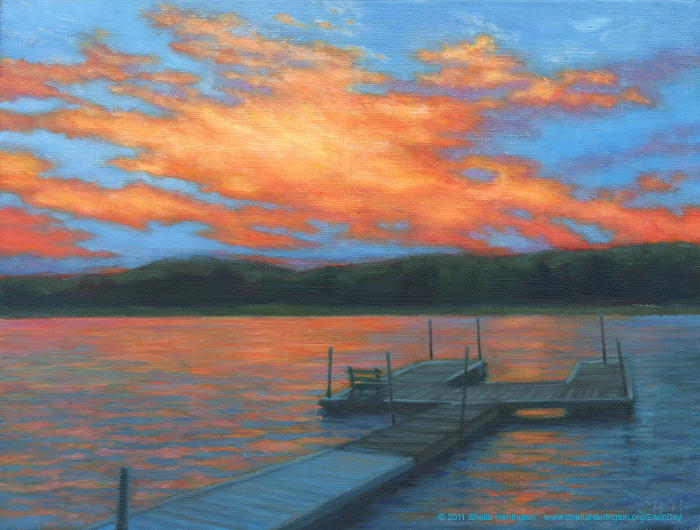

Sunrise, Deep Creek Lake

Today is the birthday of Pablo Neruda (1904-1973) and so I post this poem and its English translation, along with a painting created for our friend Martha, who introduced us to what is probably our family’s most beloved vacation destination. Thank you, Martha.

Oda a la luz encantada

La luz bajo los árboles,

la luz del alto cielo.

La luz

verde

enramada

que fulgura

en la hoja

y cae como fresca

arena blanca.

Una cigarra eleva

su son de aserradero

sobre la transparencia.

Es una copa llena

de agua

el mundo.

—Pablo Neruda

Ode To Enchanted Light

Under the trees light

has dropped from the top of the sky,

light

like a green

latticework of branches,

shining

on every leaf,

drifting down like clean

white sand.

A cicada sends

its sawing song

high into the empty air.

The world is

a glass overflowing

with water.

—Pablo Neruda

Summer in the South

Today is the birthday of writer Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906), a once-upon-a-time resident of Washington, DC, and the child of former slaves. His father had escaped through the Underground Railroad and fled to Canada, returning to fight in a Massachusetts regiment upon the outbreak of the Civil War; his mother, freed by emancipation and on the verge of emigrating to Liberia, instead decided to remain in the U.S. when the war ended. They met and married post-war in Dayton, Ohio, where Paul was born.

Dayton was a 19th century rural-to-urban destination for southern African-Americans, who quickly established churches, schools, newspapers, and small businesses. Paul’s mother, sure that he showed promise, enrolled herself in night classes (during the day she worked as a cook and laundress) in order to be able to teach her son to read. She encouraged his early interest in writing, and he produced his first poems at age six and began reciting them publicly at nine. In 1887, Ohio abolished racial segregation in the school system (although extracurricular activities like plays and dances remained segregated), and Paul attended local schools as the only African-American student, serving as high school class president and writer and editor for the school paper.

Despite his excellent school record and his having had several pieces of work published in local newspapers, Dunbar found it impossible as an African-American to find either employment in journalism or funds for college. Instead he began working as an elevator operator in the Callahan Building, a seven-story “skyscraper” in downtown Dayton, writing in his spare time. A former teacher’s recommendation acquired him a place reciting his poetry at a convention in Dayton of the Western Association of Writers, and his writing and beautiful voice so impressed the listeners that a nationally distributed write-up of the event brought Dunbar broader attention.

His old school friend Orville Wright, who had dropped out of high school to start a small printing company—having built a press with his brother Wilbur (this in their pre-flight days)—helped Dunbar to self-publish a collection of his poems. Dunbar sold these to his elevator passengers for a dollar apiece, probably hoping that as many as possible would ride all the way to the seventh floor (“While you’re riding with me today, might I interest you in some poetry?”) and eventually recouped his investment. Lucky the buyer with the presence of mind to hang onto that first edition.

Travel and exposure brought Dunbar contacts and supporters, some of them fellow writers. On a visit to Chicago to write about the 1892 Columbian Exhibition, Dunbar met and was befriended by Frederick Douglass. With the patronage of a superintendent of the Toledo State Hospital, Dunbar went on to publish further collections of his work, which were also well-received. Dunbar wrote his poetry both in standard English and in southern dialect, which he had learned through stories from his mother’s Kentucky childhood; the use of dialect in his work has suggested comparisons with Mark Twain.

His growing reputation led to a series of recitals around the U.S. and eventually a six-month recital tour in England, where he also collaborated on theatrical and choral pieces and an operetta. When he returned, it was to Washington, DC and a position at the Library of Congress, meanwhile writing in his free time a collection of short stories and his first novel. The work at the Library was less rewarding than he had hoped, and a whole lot dustier, exacerbating his developing tuberculosis, and with his wife’s encouragement he returned to writing and reciting full-time.

The subject matter for Dunbar’s fiction was drawn from life in black America, and, despite its somber themes, tended to optimistic conclusions. Later criticized for somewhat stereotypical characterizations and a tendency to sentimentality, his writing was unusual in its exploration of the difficulties of African-Americans, both pre- and post-Civil War. In this respect, and particularly in his work in dialect, he influenced later writers of the Harlem Renaissance.

Sadly, Dunbar succumbed to tuberculosis in 1906. During his short life he produced nearly two dozen books: collections of poetry and short stories, novels, and other works. Nevertheless, one can’t help wondering what direction his writing would have taken had he been able to live beyond the age of thirty-three.

Here is one of his poems, “Summer in the South,” and a recently-completed painting to accompany it.

To see where Paul Laurence Dunbar lived and worked in the nation’s capital, you can consult the illustrated Literary Map of Washington, DC.

The oriole sings in the greening grove

As if he were half-way waiting,

The rosebuds peep from their hoods of green,

Timid and hesitating.

The rain comes down in a torrent sweep

And the nights smell warm and piney,

The garden thrives, but the tender shoots

Are yellow-green and tiny.

Then a flash of sun on a waiting hill,

Streams laugh that erst were quiet,

The sky smiles down with a dazzling blue

And the woods run mad with riot.

—Paul Laurence Dunbar

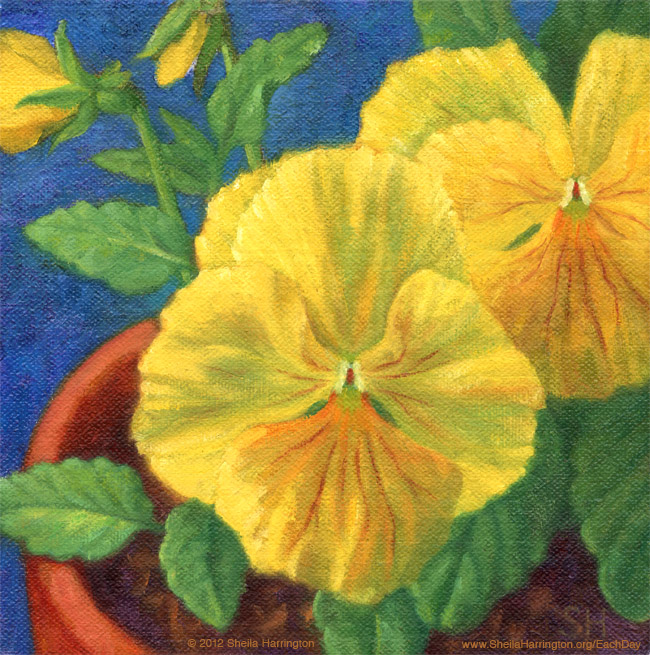

Let Me Enjoy

Today is the birthday of the sensitive and melancholy Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), who in 1897 departed England for Switzerland in order to “escape the racket of the Diamond Jubilee” (Queen Victoria’s, on that occasion). He would be obliged to go much further than Switzerland this time around, what with continuous satellite coverage of Elizabeth II’s festivities.

For his birthday I post this poem, and, despite the final verse’s mournful assumption about Hardy’s fate, I post also a painting of some cheerful yellow pansies. Since we know not the aims of the loveliness of pansies.

Let me enjoy the earth no less

Because the all-enacting Might

That fashioned forth its loveliness

Had other aims than my delight.

About my path there flits a Fair,

Who throws me not a word or sign;

I’ll charm me with her ignoring air,

And laud the lips not meant for mine.

From manuscripts of moving song

Inspired by scenes and dreams unknown

I’ll pour out raptures that belong

To others, as they were my own.

And some day hence, towards Paradise

And all its blest—if such should be—

I will lift glad, afar-off eyes

Though it contain no place for me.

—Thomas Hardy

Daughters of Time

Today is the birthday of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1883), and in his honor I post this poem, along with a painting of two apples… my modest selection from the options of bread, kingdom, stars, and sky.

Daughters of Time, the hypocritic Days,

Muffled and dumb like barefoot dervishes,

And marching single in an endless file,

Bring diadems and fagots in their hands.

To each they offer gifts after his will,

Bread, kingdoms, stars, and sky that holds them all.

I, in my pleachèd garden, watched the pomp,

Forgot my morning wishes, hastily

Took a few herbs and apples, and the Day

Turned and departed silent. I, too late,

Under her solemn fillet saw the scorn.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Bawdy Botany

Today is the birthday of the Prince of Binomial Nomenclature, otherwise known as Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the Swedish naturalist who attracted crowds to his botanical lectures by openly discussing stamens, pistils, and other shocking intimate details of plant reproduction. For sketches and a mini-bio, please see Prince of Binomial Nomenclature.