For another Mardi Gras illustration, please see Two-Part Tuesday.

Tag: Dog

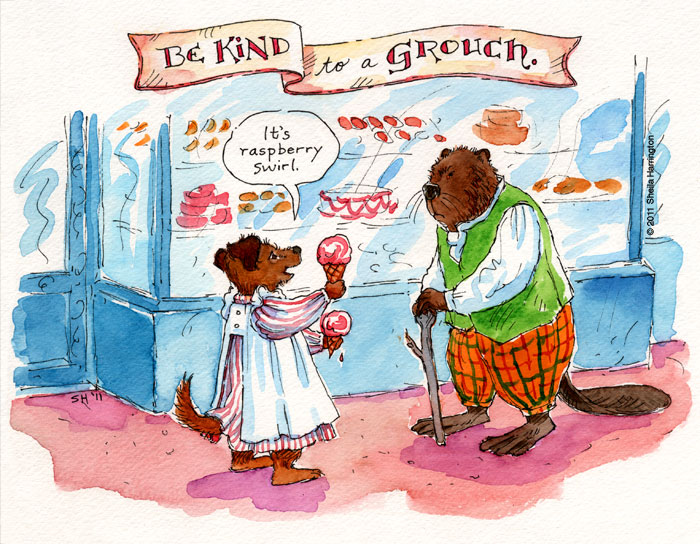

New Year’s Resolution: Random Acts

The Secret of the New Jersey Town

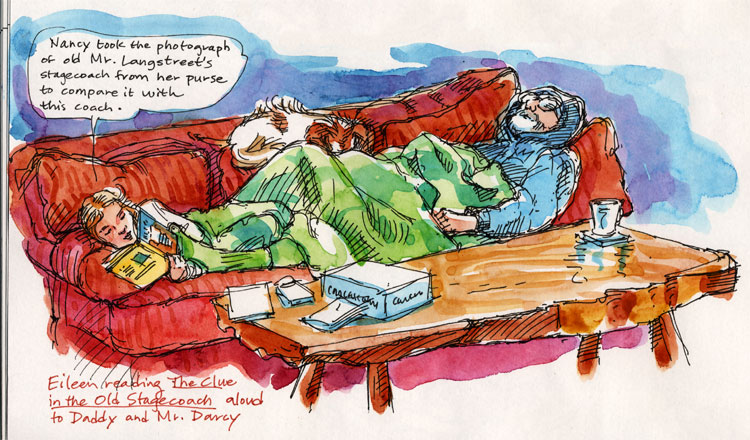

This spring we visited Maplewood, New Jersey, where my husband grew up. In exploring his old haunts, like the town library, we discovered that Maplewood, New Jersey is the Home of Nancy Drew! (The library carries the entire collection.) Not to mention the Bobbsey Twins, and the Hardy Boys, and Tom Swift! I don’t see how my husband could have lived there all those years without realizing he was sharing his home town with so many celebrities. (Actually, with the publisher of their series.) I think he was busy reading the Horatio Hornblower stories.

Well, with a daughter making her way through the Nancy Drew books, he now has total Nancy Drew Awareness. Here they are having some father-daughter-dog time. I’m fairly sure he’s awake. My husband, not the dog.

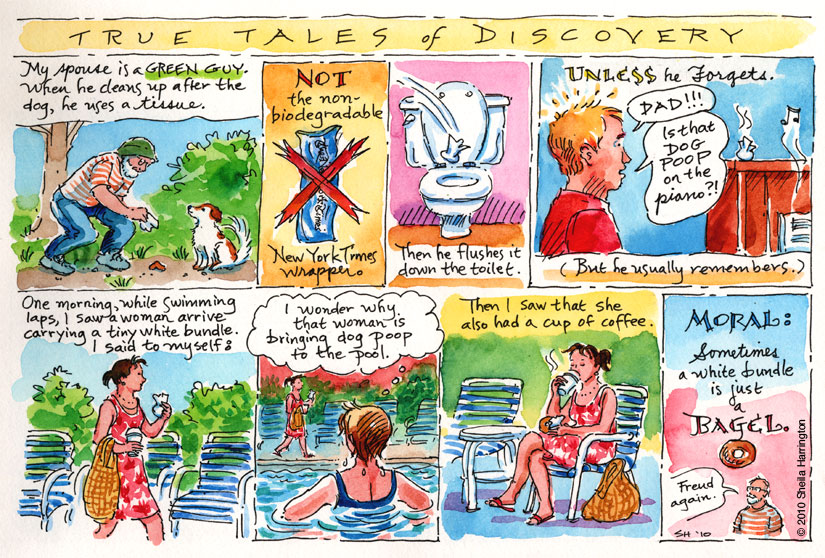

Look Before You Leap

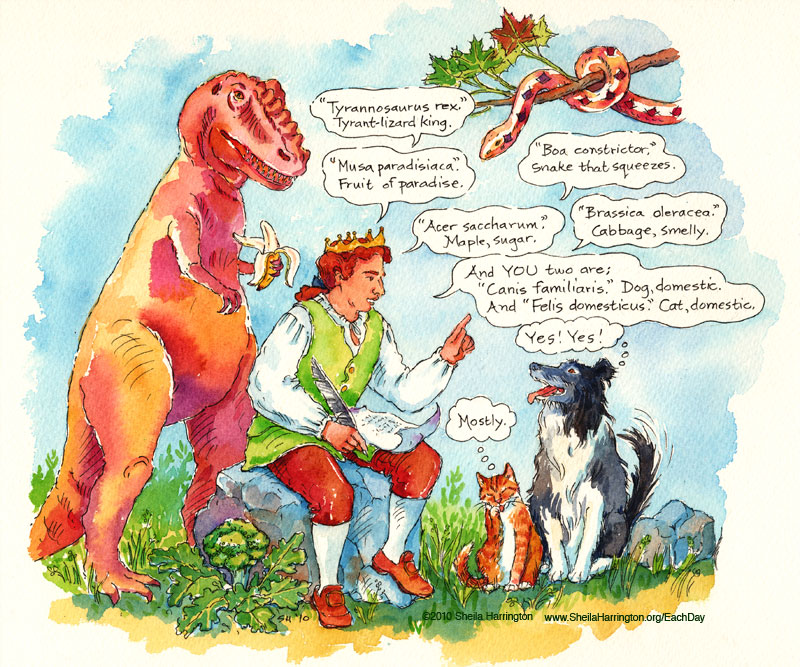

Prince of Binomial Nomenclature: Part 2

Continued from Prince of Binomial Nomenclature: Part 1, May 23rd

Longing to expand his perspective, Linnaeus applied for and received a grant for a field expedition to Lapland, a rugged region above the Arctic Circle, where he expected to find many unrecorded species. Linnaeus spent five months exploring and studying rocks, plants, insects, animals, and people, and returned with thousands of specimens (no people though), filled with excitement. He returned to lecturing, and planned a series of books cataloguing species according to his new system.

Linnaeus DID actually long for a reproductive life of his own. He paid court to a young lady whose father, not taking a wandering botanist very seriously, insisted that Linnaeus wait three years and meanwhile establish some means of supporting a family. So Linnaeus went off to Holland, whose universities were better equipped than those of Sweden, to complete his medical degree. He also found work there managing and classifying the contents of Dutch zoological and botanical gardens.

THEN, in 1735, while still in Holland, he published his book Systema Naturae, which explained his concept of classification. Linnaeus grouped plants and animals into genera—groups whose members have something in common, usually structural or related to reproduction. (Linnaeus was the first to classify whales as mammals.) Then he subdivided each group into species. (His complete heirarchy, as you may recall from high school, is Kingdom, Class, Order, Genus, and Species.) And then he gave each member a two-part name based on these divisions, replacing all previously-used cumbersome lengthy descriptions. These two-part names were in Latin, which was, and still is, the universal language of science. I told you those Latin classes would come in handy.

Systema Naturae hit the botanical world like a bolt of lightning. The notion that PLANTS (seemingly so innocent!) had a Sexual Life, by which Linnaeus partly categorized them, was outrageous and horrifying to some naturalists, and Linnaeus was criticized for “nomenclatural wantonness.” But, despite objections on both theological and moral grounds, Linnaeus’ achievement launched him from obscurity to fame. A binomial concept had been proposed by Swiss botanist Gaspard Bauhin in 1623 but was never widely used. When Linnaeus combined it with his new categorization methods, the idea spread rapidly. Here was a practical tool: reasonable, memorable, universally applicable. Not only could scientists from different countries know they were communicating about the same species; it was even easy for amateurs to use, and it sparked a more widespread interest in natural history. Such is the effect of nomenclatural wantonness.

Now back in Sweden as an established botany professor, Linnaeus was able to marry his fiancée, although he spent so much time away on expeditions that she might have been happier with one of her other suitors. He lectured, wrote many works on botany, corresponded with other naturalists, revised and expanded Systema Naturae many times throughout his life (it eventually reached 2,300 pages), led collecting expeditions, and inspired his students to travel throughout the world as botanical and zoological explorers. One circumnavigated the world with Captain Cook. Others went to North America, Japan, China, and Southeast Asia, returning with specimens (or occasionally dying in a distant land; collecting could be dangerous work). Eventually he was knighted for his contributions to science and became Carl von Linné. So there, Mom and Dad.

Linnaeus himself gave scientific names to 4,200 animals and 7,700 plants, generally choosing names to reflect physical qualities, but occasionally to honor a friend or colleague, or, with a particularly ugly or toxic specimen, to insult someone who had annoyed him. Be wary of affronting a botanist. They are still lurking out there today…naming species.

With some modifications due to our modern understanding of evolution, Linnaeus’ system is still in use today, and pretty much taken for granted. But whenever you say Homo sapiens, or Boa constrictor, perhaps now you will think of Carolus Linnaeus, who made it possible, and you will celebrate his birthday every May 23rd. If you weren’t doing so already.

Throughout his life Linnaeus was a deeply religious fellow. He saw his work as clarifying for the world the underlying connections among living things and confirming the intelligence of a great Creator. Ironically, however, because his work made possible far greater understanding and communication among naturalists everywhere, it led to observations of surprising patterns and eventually to the shocking speculation by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace that species, instead of having been from their Day of Creation exactly as we know them now, had perhaps changed over time. Over a long, long time. We do not know the ultimate consequences of our life’s work.

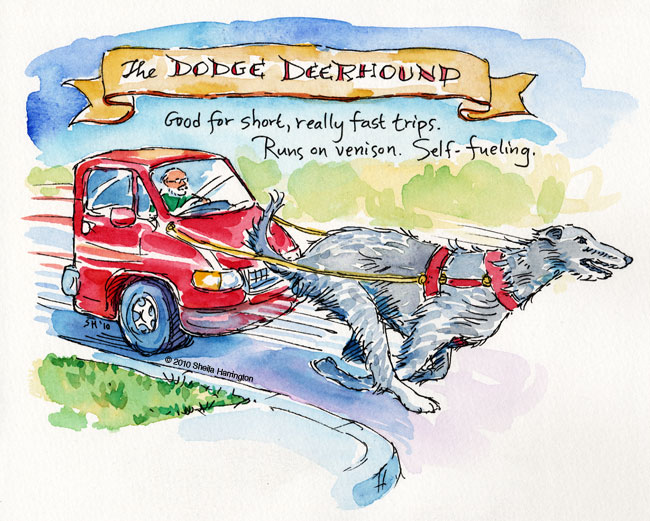

Energy-Efficient Vehicle #1

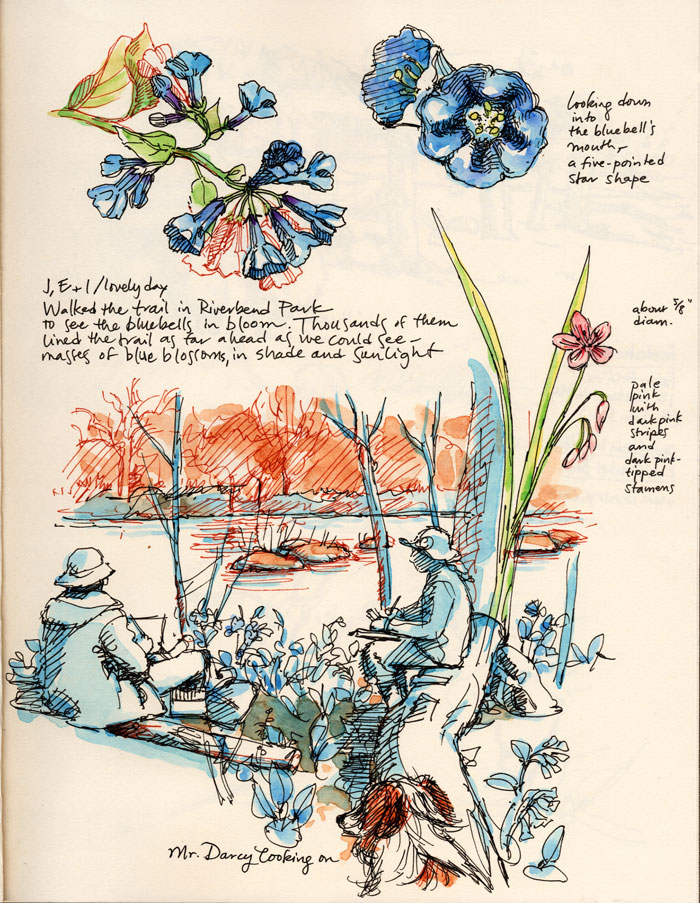

Bluebell walk

Moral Evolution of Dogs

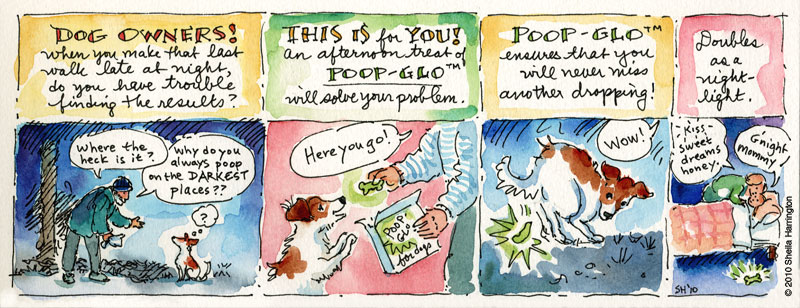

Poop-Glo

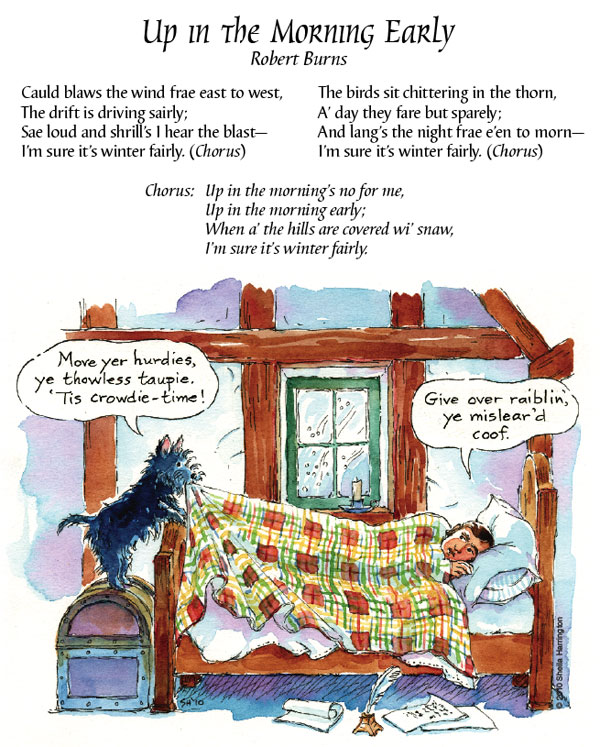

Move Yer Hurdies

Today is the birthday of Robert Burns (1759-1796), national poet of Scotland, who wrote over 900 poems and songs and collected and made available hundreds of traditional Scottish songs as well. This is all the more astounding when you consider his impoverished background, spotty education, delayed launch into literary life, and, sadly, his premature death at age 37. All over the English-speaking world today, Burns’ birthday is celebrated with recitation of his poetry; the festive presentation, and even the consumption, of haggis; toasts, speeches and songs; and a concluding round of Auld Lang Syne.

Although Burns is probably best known for his beautiful and poignant love poems, generally written in honor of one of the numerous ladies Burns admired, my offering today is a seasonal verse appropriate for a Monday morning in January.

Translation:

Move your buttocks, you lazy fool. It’s breakfast-time!

Stop talking nonsense, you unmannerly blockhead.