If the word “Xanadu” happens to come up at our dinner table (and doesn’t it come up from time to time at yours?) we can count on our son’s launching into Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” which he memorized at some point due to sheer fascination with the language.

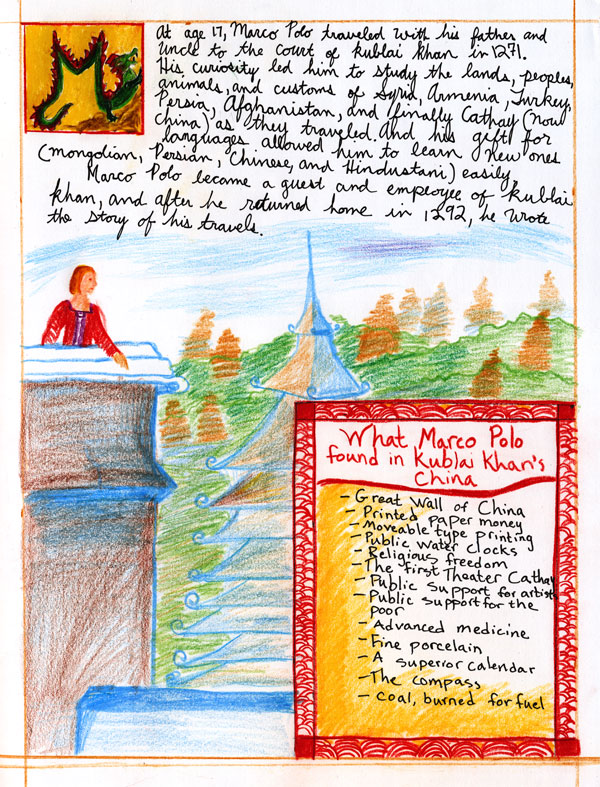

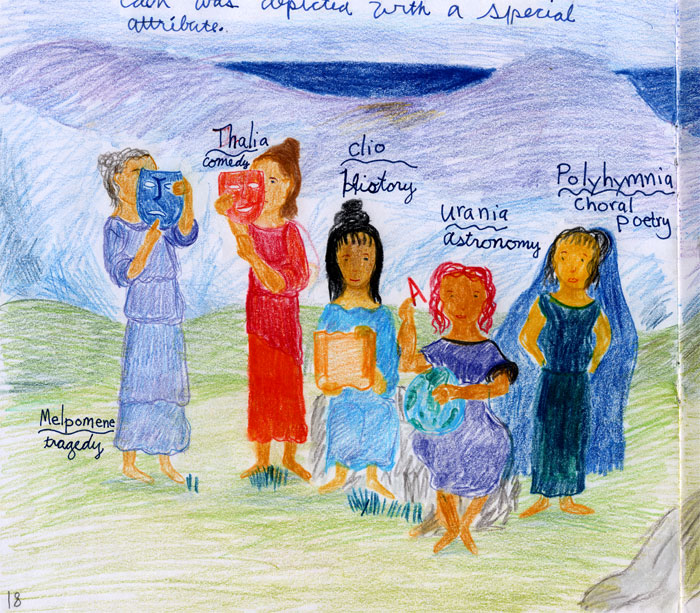

Today is the birthday of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), and in his honor I post the opening lines of that poem. Along with it I post my daughter’s drawing, from our homeschooling Middle Ages block, of the rooftops of Xanadu, the summer residence of Kublai Khan (grandson of Genghis Khan), who ruled China during the years of Marco Polo’s visit and subsequent years of service to the Khan.

Cambalu, the winter capital, grew quite hot in summer, so Kublai had a northern marshy river valley drained and transformed into a vast park of gardens, teahouses, terraces, and winding waterways for pleasure boats and wild birds. (Here is Marco surveying the scene from a rooftop.) At its center was the palace of polished bamboo painted with vermilion and gold and elaborate murals.

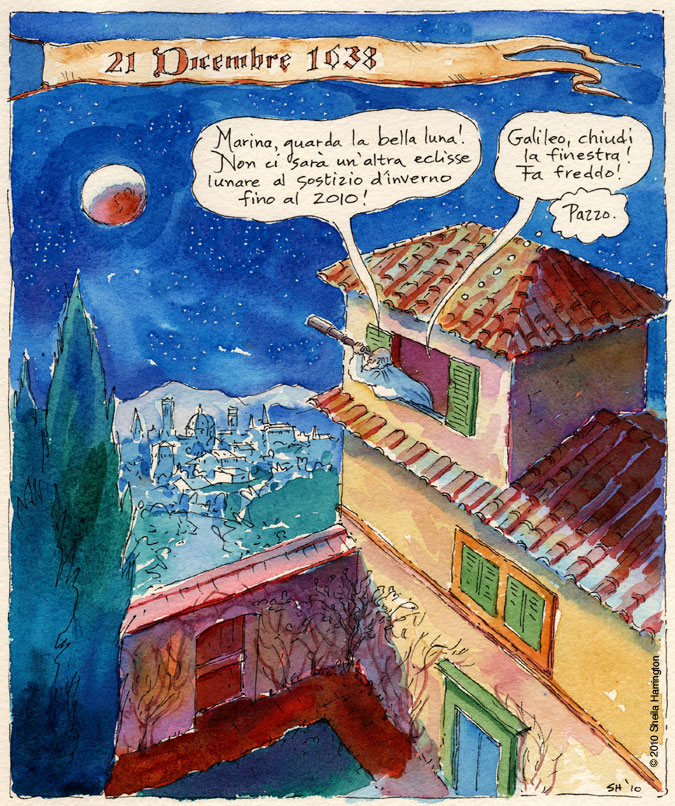

Xanadu was destroyed in the 14th century, but Marco Polo’s descriptions were familiar and inspirational to later writers, one of whose works (Samuel Purchas’ 1613 Purchas His Pilgrimage) Coleridge had been reading one summer day in 1797 before falling into a deep, some say drug-induced, sleep. While he slept, Coleridge “dreamed” the poem as a series of vivid and haunting images and phrases, which he instantly wrote down upon awakening.

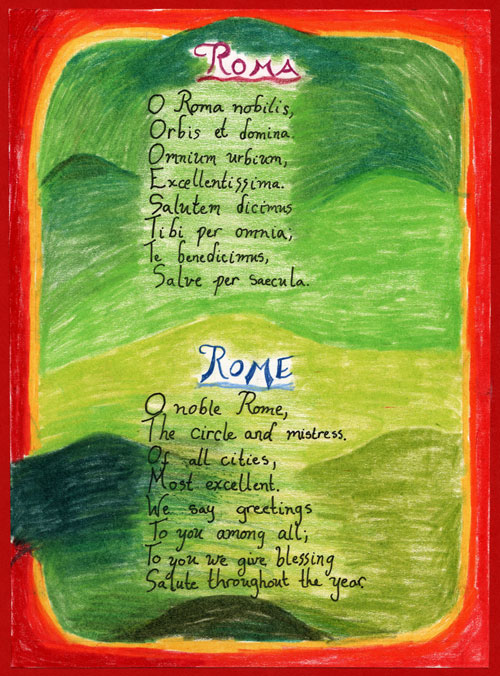

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan A stately pleasure-dome decree: Where Alph, the sacred river, ran Through caverns measureless to man Down to a sunless sea. So twice five miles of fertile ground With walls and towers were girdled round; And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills, Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree; And here were forests ancient as the hills, Enfolding sunny spots of greenery…For the rest, please see Poetry Out Loud. You will want to memorize it, too.

For another Coleridge poem, and a painting, please see Thou shalt wander like a breeze.