Continued from April 28th, Part I.

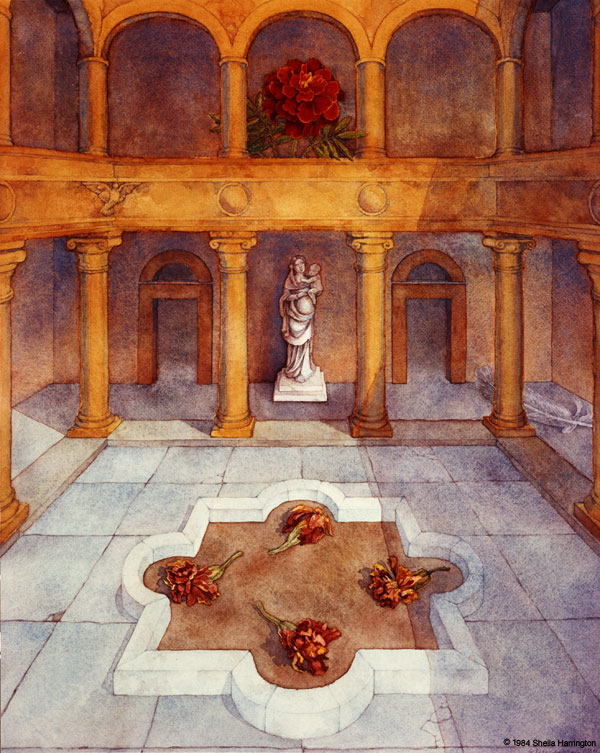

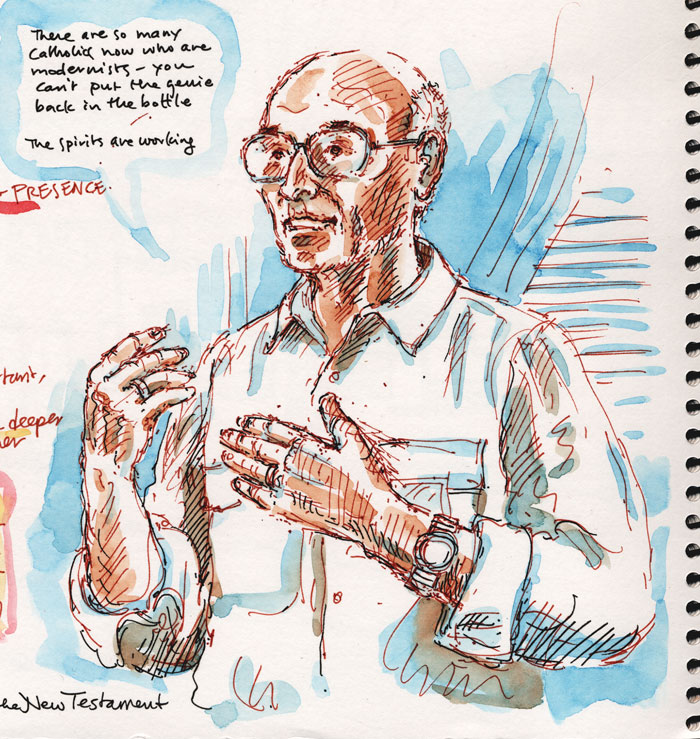

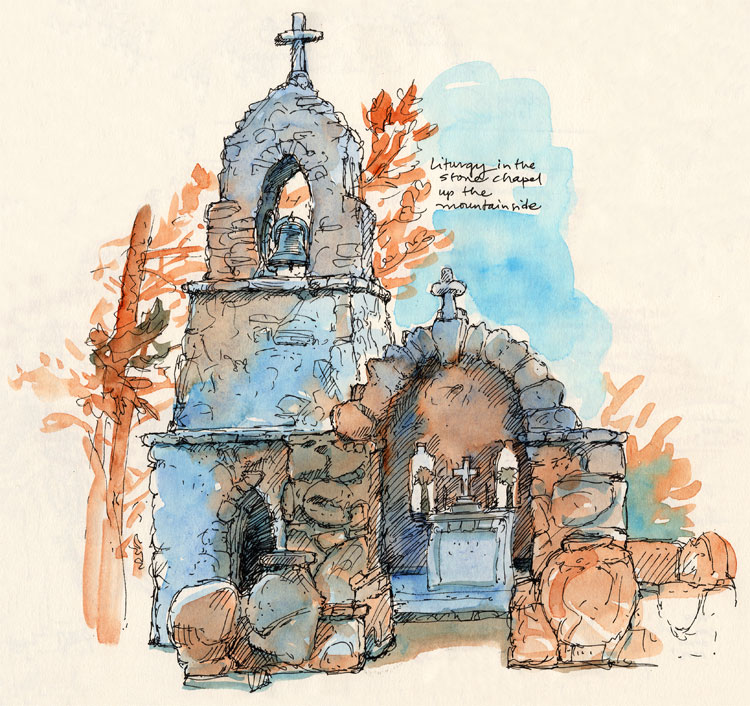

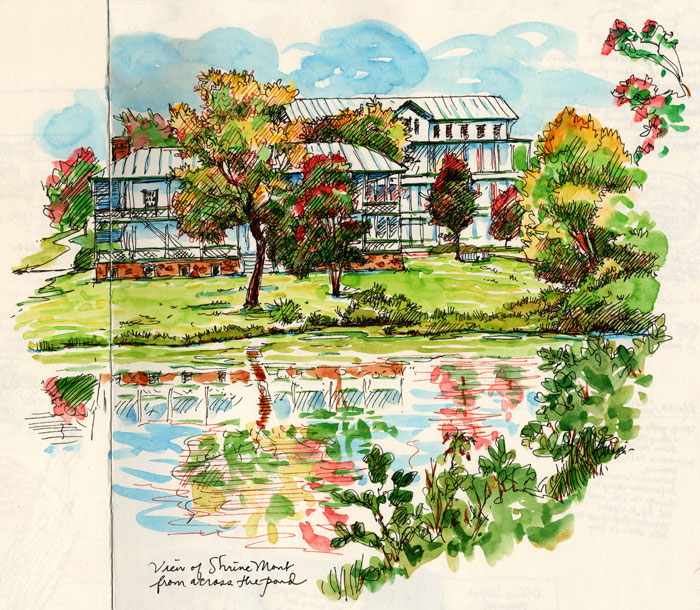

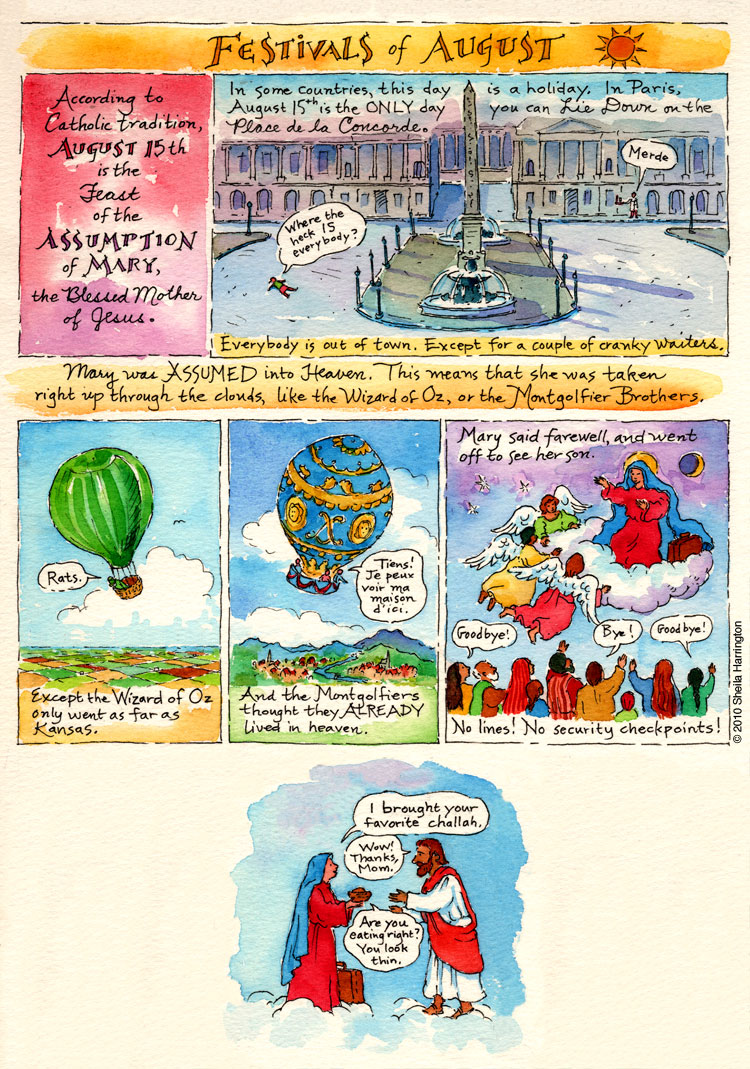

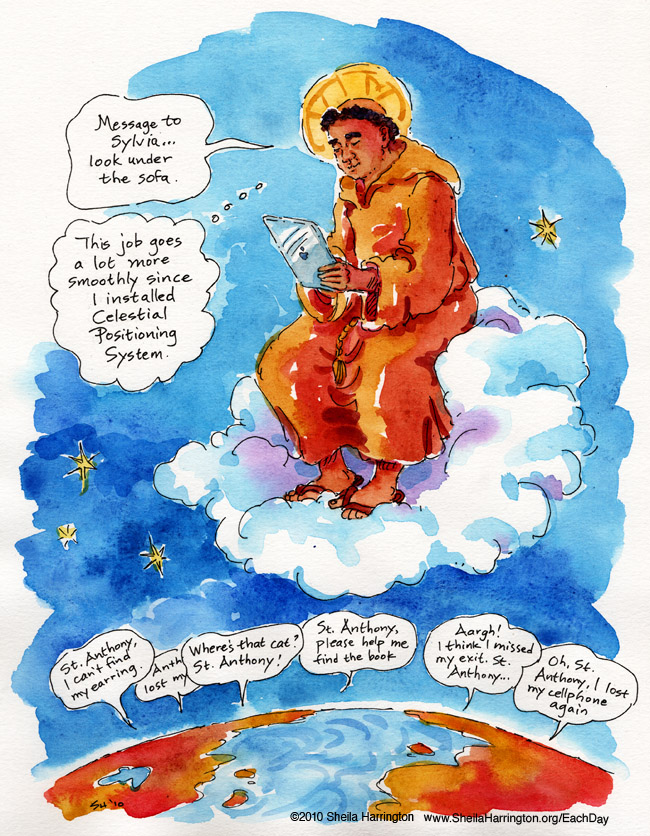

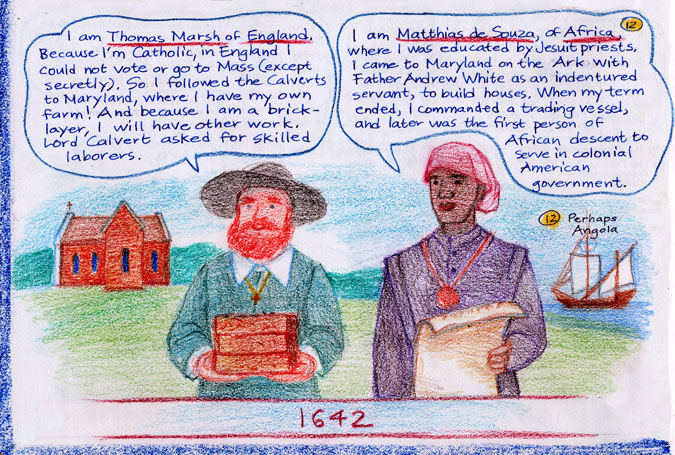

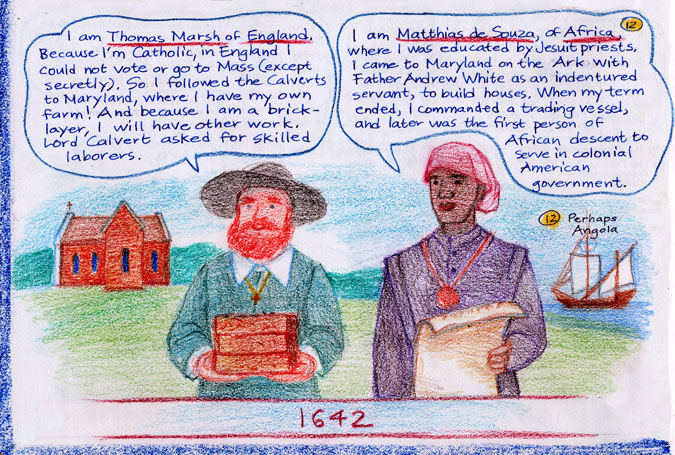

Pictures are from our homeschooling block, Local History and Geography.

Despite Maryland’s absence of gold, colonists benefited from another resource: tobacco, which grew well and had a ready market in England. It quickly became Maryland’s principal cash crop. (In rural areas tobacco was used to pay bills even into the 20th century.) Some planters made large fortunes and imported their style of living from England, spending their time at hunting meets, dances, card parties, horse races, and similarly useful pursuits.

Tobacco rapidly depleted the soil, however, requiring continual acquisition of acreage and labor, both hired and slave, and pushing Native Americans further from their homelands. In the first half of the 18th century, England helpfully sent 10,000 convicts, mainly petty thieves and other troublesome folk, to Maryland as indentured servants. But while they worked off their indentures and freed themselves, the slave population, permanently trapped, increased. (And that’s another story.)

Maryland’s coastlines were settled first, so when German and Scotch-Irish immigrants began to arrive in the 1740s, they moved into western Maryland, creating small farms like those in Europe and New England, raising animals, growing grains (rather than tobacco) on manured fields, rotating their crops, and feeling exasperated that large wasteful eastern plantation-holders had more say in land and trade policy than they did themselves. Iron was discovered in western Maryland, and its mining and forging, mostly by slaves, accelerated rapidly. The port of Baltimore grew as grain and iron passed through for the French and Indian Wars, warfare being ever a boon to industry. Annapolis very slowly became a center of society, acquiring the attendant accoutrements of high culture: a theater, newspaper, bookshop, and jail.

In 1763-67 the final, and very peculiar, shape of Maryland was determined when astronomer Charles Mason and surveyor Jeremiah Dixon were hired to resolve an old boundary dispute between Maryland and Pennsylvania due to overlapping land grants made in the 17th century. They marked the border with 230 stones,

some of which remain today, little knowing that their boundary would come to be regarded—inaccurately—as the division between slave and free territory.

By the 1770s, the now-numerous settlers (Maryland’s population was about 150,000, which included tens of thousands of African slaves and a few hundred remaining Native Americans) were inevitably, due to time, distance, and differences, less connected to Great Britain. In 1713 the currently reigning Calvert had converted to Protestantism. But Marylanders didn’t want ANY Proprietor, of any religion whatsoever. Parliament’s taxes and trading practices favoring Great Britain infuriated them, as it did colonists elsewhere. Although some were at first unsure about complete independence, Maryland sent delegates to the First Continental Congress in 1774. Four signers of the Declaration of Independence were from Maryland, including the only Catholic. Maryland militiamen fought with George Washington in the Revolutionary War (the state’s sole Tory regiment was chased across the border and later departed for Canada).

After the war finally ended in 1783—people forget how LONG it dragged on—and after the delegates to the Constitutional Convention spent the summer of 1787 heatedly wrangling over the creation of the Constitution (which story reads like a thriller in itself), Maryland ratified it the following spring, becoming the seventh of the new United States. Not only that, but Maryland provided two of the nation’s seven temporary capitals (Baltimore and Annapolis) throughout its formative years, and finally the permanent one in 1790: Washington, District of Columbia, carved from a 10-mile square on the Potomac. (Virginia took back its section in 1846.)

So, party down, Marylanders! and celebrate your stateliness by singing the Official State Song (to the tune of “O Tannenbaum”). Here are the first two verses. Just in case you don’t already know them by heart.

The despot’s heel is on thy shore,

Maryland!*

His torch is at thy temple door,

Maryland!

Avenge the patriotic gore

That flecked the streets of Baltimore,

And be the battle queen of yore,

Maryland! My Maryland!

Hark to an exiled son’s appeal,

Maryland!

My mother State! to thee I kneel,

Maryland!

For life and death, for woe and weal,

Thy peerless chivalry reveal,

And gird thy beauteous limbs with steel,

Maryland! My Maryland!

* Although the words as written, and as adopted by statute, contain only one instance of “Maryland” in the second and fourth line of each stanza, common practice is to sing “Maryland, my Maryland” each time to keep with the meter of the tune.

Michaela

Michaela

John

John