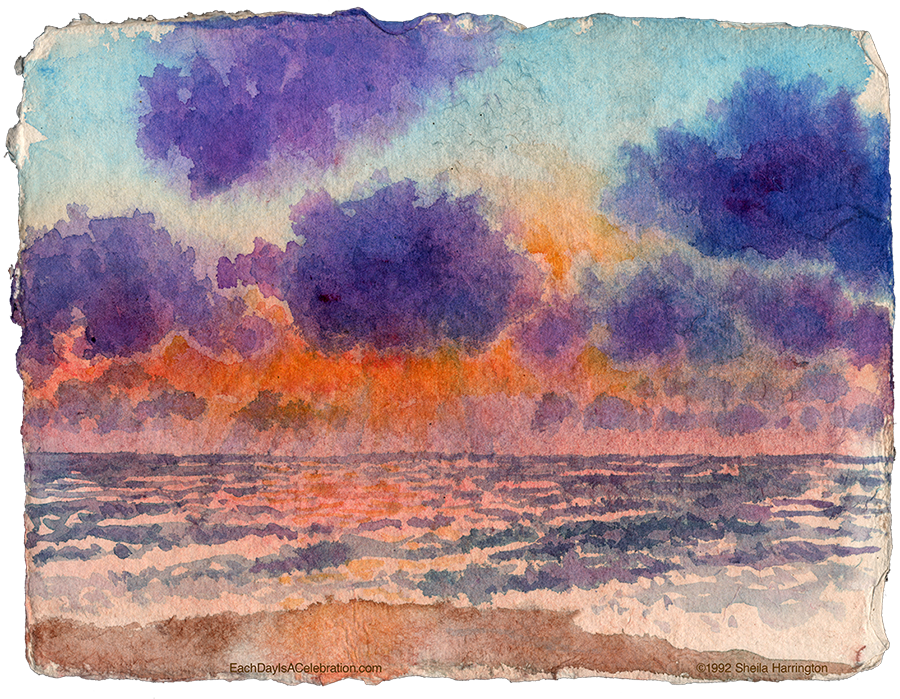

I post this painting and verse (“An Hymn to the Morning”) in honor of poet Phillis Wheatley (circa 1753-1784). Her birth date, and in fact her birth year, are unknown, but today is the anniversary of the day that she was emancipated from slavery. So we might think of that as a kind of birthday.

I chose this image to accompany her poem partly because of its depiction of dawn, but also because it was, unhappily, across the sea that Wheatley came to these shores, kidnapped in West Africa by slavers and sold in Boston. Her age was estimated at around seven or eight, because she had “already lost her front teeth,” a fact that clutches at the heart of any parent reading this unembellished observation. Or of anyone who knows a child… or remembers being a child. No tooth fairy for her, though. Her birth name went unrecorded, and her new owners blithely and undoubtedly without irony gave her the name Phillis, the name of the slave ship that had brought her to Boston, adding their own surname.

Phillis was a thin, sickly child (unsurprising, after such a voyage), and although she was nursed and raised more as a child of the house than a slave, she remained delicate all her short life. Her owners soon recognized that Phillis was bright and precocious and put her education into the hands of their grown daughter Mary. Within sixteen months Phillis was fluent in English and could read even difficult passages in the Bible. Her education included Classical and English literature, geography, history, and Latin, as well as the ubiquitous Bible, and volumes of poetry—an unusual education for a woman of the day, let alone an African slave. (Mary had probably been given the same education.)

At around age twelve, Wheatley began writing her own poetry, and her first published work appeared in a Newport newspaper when she was fourteen. She felt a powerful drive to create poetry, and her owners encouraged her and assisted in its publication in journals in the colonies and in England. Much of the subject matter was quite somber, consisting of tributes to noteworthy personages of the day and elegies composed upon the death of someone’s spouse or child. They are complex in their use of language, employing ambiguity and subtle understatement, and allusions to Greek and Roman history and mythology as well as to the Bible. Wheatley was obviously assuming similar education on the part of her audience, and it’s pretty rough sledding for the 21st century reader. I liked this particular poem because of the rare note of humor in the closing lines, and was glad to imagine her having a small chuckle.

It wasn’t long before Wheatley’s poetry brought her attention. Her owners, unable to find a colonial backer to publish a book of her work, found a publisher in London, who agreed to the project if the work could be prefaced by a statement signed by respectable Bostonians testifying to its authenticity! Phillis was questioned by Boston’s judges, and the required document was procured (one of its 18 signers was John Hancock).

So off she went to England, accompanied by her owners’ grown son, where she spent several months overseeing the publication of her book and meeting both members of the nobility and free Britons of African descent. She was a celebrity. In England there was public criticism of Phillis’ American enslavement, which embarrassed her owners. It probably would have been possible for her to refuse to return to America, and to stay where she would have been free; nevertheless, on hearing of her mistress’ illness, she boarded ship for home, missing an upcoming opportunity to be presented at court. And shortly after her return, her owner signed her emancipation papers.

She was free. What did that mean? Well, that her books belonged to her, and thus she attempted to sell them to help support herself. She authored a tribute to George Washington, who invited her to come call on him, as he wished to meet “the little black poetess.” Phillis had hopes for the Revolution—that the new country, once freed from Britain’s yoke, would turn around and free its own yoked people. Her poetry, which had been ambiguous in its references to slavery, grew more clearly critical. Although she continued to write, while struggling to earn a living as a cleaning woman, she died young, ill and destitute.

Happy Emancipation Day, Phillis. With your gifts and your drive to create, what would you have become in another era? Undoubtedly a published author of many works, interviewed by journalists, embarking on author tours, launching podcasts.

Attend my lays, ye ever honour’d nine,

Assist my labours, and my strains refine;

In smoothest numbers pour the notes along,

For bright Aurora now demands my song.

Aurora hail, and all the thousand dies,

Which deck thy progress through the vaulted skies:

The morn awakes, and wide extends her rays,

On ev’ry leaf the gentle zephyr plays;

Harmonious lays the feather’d race resume,

Dart the bright eye, and shake the painted plume.

Ye shady groves, your verdant gloom display

To shield your poet from the burning day:

Calliope awake the sacred lyre,

While thy fair sisters fan the pleasing fire:

The bow’rs, the gales, the variegated skies

In all their pleasures in my bosom rise.

See in the east th’ illustrious king of day!

His rising radiance drives the shades away–

But Oh! I feel his fervid beams too strong,

And scarce begun, concludes th’ abortive song.

— Phillis Wheatley![]()