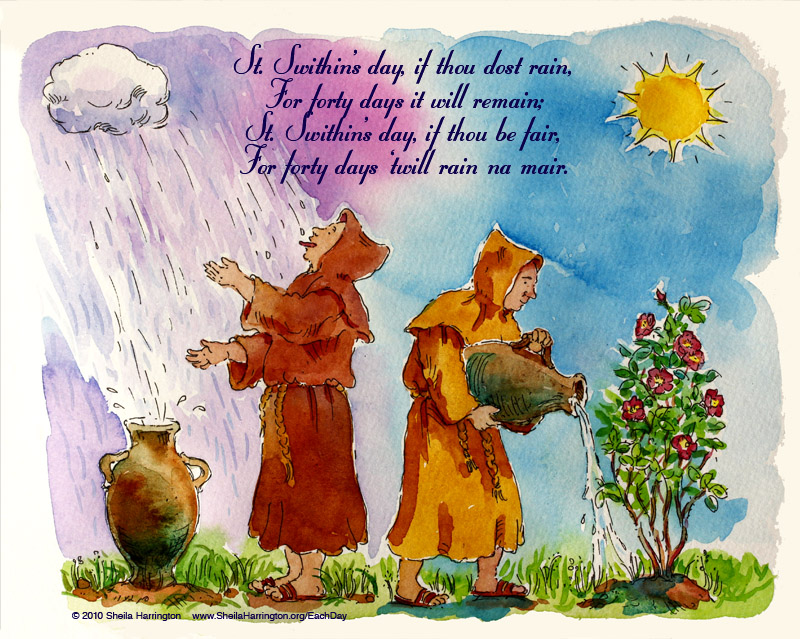

Look out the window. Doth it rain today, or doth it shine? Prepare yourself. Today is the feast day of St. Swithin, and for the next forty days you can plan your activities and wardrobe according to the old verse.

Swithin was born in the 9th century—the precise year is unknown—in Winchester, England, during the reign of King Egbert of Wessex, who ruled from 802 to 839. There are but a few reliable facts of his life, drawn from church records. Nevertheless, there must have been something about the fellow, for, both during his life and afterward, he inspired numerous stories and customs that have endured for the last twelve centuries.

Swithin was ordained as a monk and gained such a favorable reputation that he was selected as a tutor to Egbert’s son Aethelwulf. When Aethelwulf himself became king, he appointed his former tutor as bishop of Winchester, where for the next ten years Swithin built numerous churches as well as the town’s first stone bridge. Nevertheless he apparently remained a modest, unassuming fellow, charitable and sensible, preferring to go about on foot, avoiding ostentation. He also managed to convince Aethelwulf to donate a tenth of his own lands to pay for some of the church-building. Swithin’s dying request was to be buried not indoors within an elaborate shrine, as was customary with prominent folk, but outside in a simple churchyard grave, where “the rain may fall upon me, and the footsteps of passers-by.” When he died in 862, his request was granted…for a while.

But a hundred years later, when the bishops of Canterbury and Winchester were renovating the church and undertaking reforms, they cast about for relics of a saintly candidate to inspire their parishioners. Swithin had the fortune, or misfortune, to be associated with numerous miracles both before and after his death, among them the healing of ailments of the eyes and the spine, and the kindly repair of an elderly woman’s broken eggs so that they were good as new, a miracle that would certainly come in handy in any household. What luck to find a local guy that no one had yet claimed! The two bishops decided to elevate unpresumptuous St. Swithin to more prominent status. What better way than to remove his body from its humble grassy setting and place it in a more visible shrine within the newly renovated church?

Well, as the story goes, when they set about digging up Swithin, the sky clouded over, and a heavy rain began that continued for the aforementioned forty days. This would certainly indicate heavenly displeasure, if one were inclined to interpret such signs. But it did not deter the church authorities, who persisted in their plan and not only dug up St. Swithin’s body but sent his head to Canterbury Cathedral and his arm to Peterborough Abbey, rather than selfishly keep the entire saint in Winchester. They also rededicated the church (formerly dedicated to St. Peter and St. Paul). At some point along the way Swithin acquired the title of “Saint,” although he was never formally canonized by the church. He is what is known as a “home-made saint,” and churches all over the British Isles are named after him.

However, despite—or perhaps because of—all this unsolicited attention, St. Swithin still has his say every July 15th, determining the weather for the following month or so. According to a study conducted in Great Britain in the last decades of the 20th century, around mid-July the weather tends to settle into a pattern that lasts until late August, and this is true for about seven out of ten years. It either has something to do with the jet stream, or with Swithin’s periodic annoyance at being kept indoors. When it rains in August, the saying goes, “St. Swithin is christening the apples.”