Sparkle

Fancy Feet

Way down at the bottom are my toes being painted in honor of my wedding anniversary. It’s hard to draw, though, when your feet are being pumiced to a fare-thee-well.

My friend Jana says the pedicure sandals look as if they are made from Necco wafers.

I realize that my feet are probably not the first thing my husband will be gazing at when we go out to dinner tonight, but an anniversary pedicure feels so celebratory.

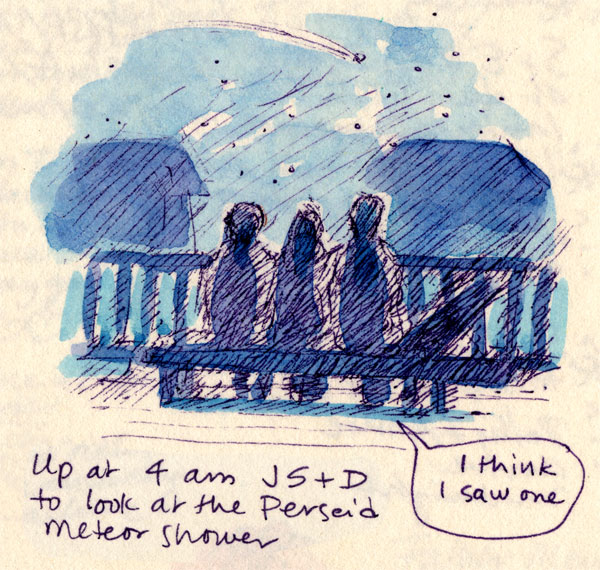

Night of the Shooting Stars

I am sad to tell you that tonight is the night of the Perseid meteor shower. Sad because here we have pouring rain and crashing thunder; not the best conditions for viewing.

A meteor shower is the debris shed by a comet as it orbits the sun, and we on Earth pass through several showers of comet-debris during the course of each year. When one of the meteors happens to enter our atmosphere, it is traveling at such a tremendous rate (thousands of miles an hour) that it’s ignited by friction—giving the impression of a falling star—and generally burns up before it hits the ground. (Sometimes a meteor makes it all the way to Earth without being consumed, in which case it is termed a meteorite. A few very large meteorites have made impressive dents in our planet.)

The Perseids are the meteors of the comet Swift-Tuttle, through whose rubble we pass in August. They are named for the constellation Perseus, because from Earth’s perspective they seem to be coming from that direction. In mid-August in this hemisphere Perseus rises in the northeast at around 11 pm or so. This year, August 12th, starting at around midnight, is supposed to be the best time for viewing the Perseids. Ha! Well, probably some of you live where it is not raining.

To view a meteor shower, it’s best to get out of the city or densely populated suburb—in other words, head for an area without lots of artificial light. In past years we have set the alarm clock (sometimes the best time is 3 or 4 am) and then gone out to sit on a deck, or lie on a rooftop, or stretch out in a big treeless field on a blanket (or, if in Vermont, shivering under the blanket) and then waited, gazing at the night sky.

Some years we’ve seen many, many. Other years (as above) we’re not so lucky. But go do it anyway. How often do we even take time to look at the Milky Way? That in itself is a rare and wonderful experience for the frazzled urban person. The additional sight of sparkling shooting stars sailing across the night sky is seriously magical.

Dig for Elephants

Eat your heart out, Boston! We have our own Big Dig in Washington, DC, at the National Zoo, and ours has elephants in it! Well, maybe it’s not quite as Big. But it’s certainly been transforming the core of the zoo for the past fifteen years—on every visit you have to navigate construction equipment and major piles of dirt, although not always the same piles—and it ain’t over yet.

First we got big splashy Amazonia Habitat with its science gallery; then Think Tank, for research into primate (as opposed to primary) education, with the crowd-wowing outdoor overhead O-Line for the use of orangutans when they decide to move between buildings. This was followed by completely redesigned panda exhibits to welcome for their honeymoon a new young panda couple, parents of hugely popular Tai Shan. Then came Asia Trail, with its green roofs, convincingly sculpted rocks, and several new endangered species for the zoo’s species preservation program.

Now the major project under way is Elephant Trails, a research and breeding program to preserve the endangered Asian elephant, which will provide an expanded herd with a more natural and environmentally friendly environment. Phase 1 opened this summer, and on a recent walk I had a look at the elephants munching breakfast near a big new stepped pond, in well-kept rolling grassy fields, like a high-end retirement home. I don’t know what the elephants think, but I’m ready to move in. You can learn more about it at the zoo’s website, and even make a donation and get your name on a plaque.

Fish

The pond in the Bishop’s Garden, from a series of paintings at Washington National Cathedral. And a poem.

AA

AA

of a fish who swims downstream. The unborn child who plays in the fragrant garden is named Mavis: her red hair is made of future and her sleek feet

are wet with dreams. The cat who naps in the bedroom has his paws in the sun of summer and his tail in the moonlight of change. You and I

spend years walking up and down the dusty stairs of the house. Sometimes we stand in the bedroom and the cat walks towards us like a message.

Sometimes we pick dandelions from the garden and watch the white heads blow open in our hands. We are learning to fish in the river

of sorrow; we are undressing for a swim.

— Faith Shearin

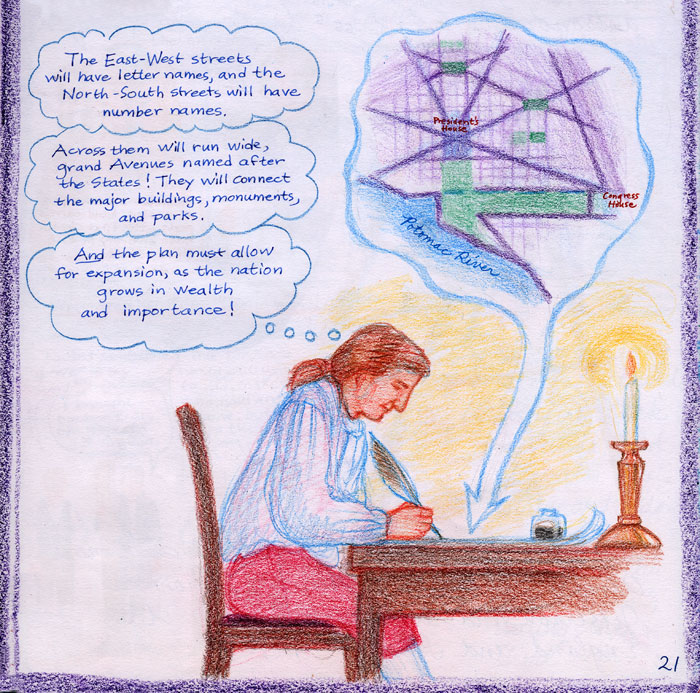

The Man with the Plan

Here is a drawing from our homeschooling Local History and Geography book, in honor of Pierre Charles L’Enfant (1754-1825), whose birthday it is today. Because of other obligations I cannot give him the lengthy post he deserves, but I hope to do him justice in 2011.

L’Enfant, an artist and son of an artist, came from France with the Marquis de Lafayette, as most Washingtonians probably know, to fight alongside the American colonists for independence, and later, having impressed the General with his battlefield sketches, was appointed by George Washington to design the United States’ new capital, Washington, DC. He created a a plan which was unfulfilled during his lifetime and has been only incompletely followed since, but which nevertheless gives us today this lovely and unusual city.

L’Enfant examined a quiet, hilly site of woodland, meadow, and marsh, uninhabited but for a handful of farms and the tiny port of Georgetown, and visualized an orderly grid overlaid by wide diagonal avenues allowing for long vistas, designed to incorporate stately public buildings, canals, bridges, squares, parks, and monuments: not simply a new bureaucratic center, but a Grand Capital for a young, energetic New Nation.

He had also a number of sensible, intelligent ideas as to how construction of the new city might have been financed, which were unfortunately never followed. Reading about the snail-like early development of the city, its wrangling political factions, its stodgy unimaginative Commissioners, and its greedy unscrupulous speculators, would make your hair stand on end. It also sounds uncomfortably familiar.

In the midst of it L’Enfant and Washington kept before them the vision of a finished work. Along the way L’Enfant, a hot-headed and demonstrative fellow, offended any number of people by vehemently defending his plans against unattractive provincial alterations (like any artist worth his salt) to the point of knocking down a new house that intruded on one of the proposed avenues. Not the way to keep your job. Which he finally lost after an exasperated Washington could no longer defend him against his many critics. L’Enfant remained bitter about his treatment—he was never paid for his work, although others made considerable sums through its implementation—and spent his remaining years as the poverty-stricken guest of a kind friend in rural Maryland, to be buried finally in their garden.

He has since been removed to a more honorable site in Arlington Cemetery, overlooking the city that finally rose to meet his expectations. Happy Birthday, Pierre, and I hope you are enjoying the view.

Water

From my sketchbook, the fountain in the courtyard of the Freer Gallery of Art, a quiet place to sit and meditate (and wish you were in that pool). And a verse for Sunday.

If I were called in To construct a religion I should make use of water. Going to church Would entail a fording To dry, different clothes; My liturgy would employ Images of sousing, A furious devout drench, And I should raise in the east A glass of water Where any-angled light Would congregate endlessly.— Philip Larkin

Look Before You Leap

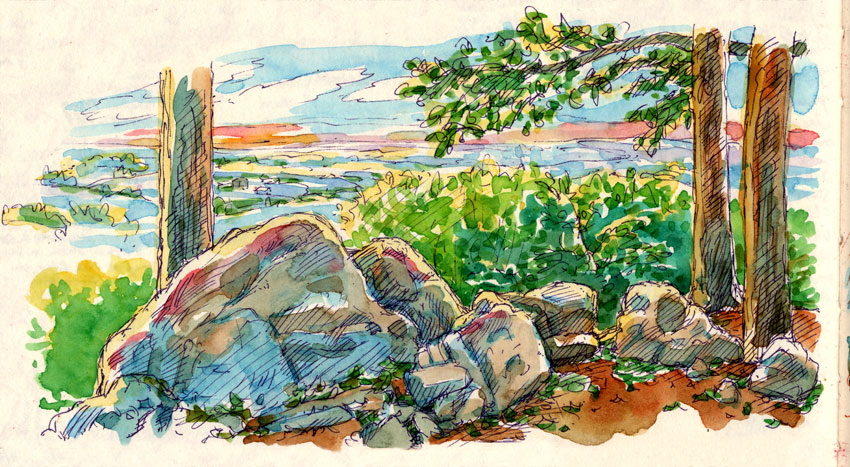

Mountain Woman Part 2

Continued from Mountain Woman Part 1, August 5

Believing that women ought to share the responsibilities as well as the rights of men, Julia requested to take her turn at the night watch, but was refused. She wrote of the guard master, “He believes that woman is an angel without any sense, needing the legislation of her brothers to keep her in her place, that, restraint removed, would immediately usurp his position and no longer be an angel but unwomanly.”

After a journey of about a month, the wagon train reached the foot of the mountains near present-day Colorado Springs and set up camp. Above them loomed Pikes Peak, which had been named for U.S. Army officer Zebulon Pike, who had come upon it in 1806, tried to climb it, and failed. (“No human being could have ascended to its pinacle [sic],” he wrote.) Despite his failure, the mountain was named for him, giving him an A for effort. In 1820 a group of government explorers finally made it to the top.

On August 1st, 1858, Julia Holmes, her husband, and two other men set out to climb Pikes Peak. The four of them carried heavy packs with food and bedding, as well as writing materials and a volume of Emerson, whom Julia admired. They had a difficult time of it, misjudging the route (no trails! no friendly National Park Service blazes!) and once running out of water. But each night, as they camped among snow-covered rocks or beside waterfalls or in a nest of spruce branches, Julia described her impressions in her journal.

When they finally reached the 14,110-foot peak on August 5th, they wrote their names on a boulder (tsk, tsk). Then Julia read aloud to the group a poem by Emerson, and stretched out upon a broad flat rock to write letters to her friends. (“Hi! You’ll never guess where I am!”) Her Pikes Peak climb gave her the nickname “Bloomer Girl.”

After that the party separated for various destinations. When Lincoln was elected President, Julia’s husband was appointed Secretary of the Territory of New Mexico, where Julia became a correspondent for The New York Tribune. She had four children, only two surviving to adulthood. Afterward they moved back East and eventually to Washington DC, where they divorced (mysteriously, and unusual for the time), and she—now a bilingual Spanish speaker—worked as chief of the Division of Spanish Correspondence for the Bureau of Education.

Like her mother, she was active in the women’s suffrage movement. After women in Wyoming and Utah Territories gained the right to vote in 1869 and 1870, women suffragists elsewhere showed up at their polls to vote, in a combination of optimism and protest; Julia Archibald Holmes is on record as one of 73 women who in 1871 made the attempt (unsuccessfully) to register to vote in Washington, DC.

As far as we know, she never climbed another geographical mountain, but she certainly scaled several metaphorical ones.