Today is the anniversary of the day in 1775 that Benjamin Franklin was appointed First Postmaster by the Continental Congress of the thirteen colonies. If you do not already know the history of the United States Post Office from the trial scene in the movie Miracle on 34th Street (the fabulous original 1947 version, not the flimsy imitation made in 1994), read on.

This method (above) of delivering mail no longer exists in the United States, except in remote outposts of Delaware, where descendants of 17th-century Swedish settlers cling to time-honored traditions.

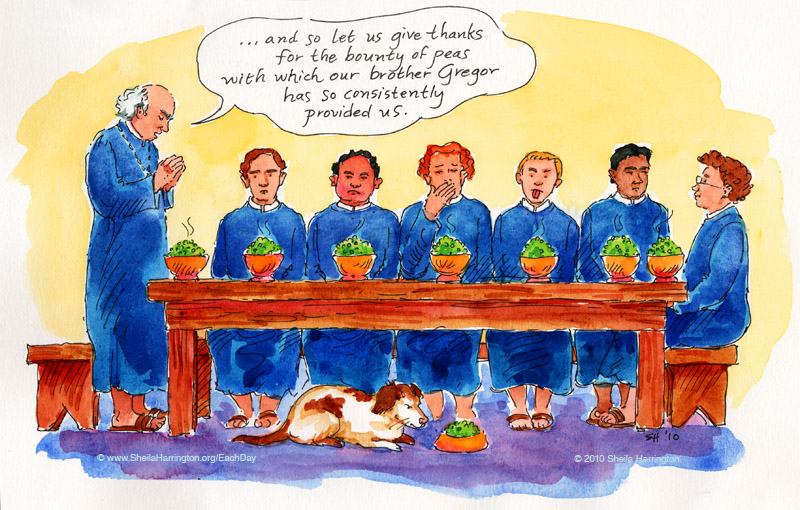

Message delivery services have been around for thousands of years. The ancient Chinese had one, as did the Mayans, and the Aztecs. The efficient postal system of Persia inspired Herodotus to write in the 5th century B.C., “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” Except he said it in ancient Greek.

When English colonists arrived on these shores in the 1600s, they were probably familiar with the recently developed London Penny Post. Send a letter anywhere in London for a penny! or elsewhere for additional fees (seems rather expensive given the era, though). The cost could be paid by either party, which occasionally discouraged someone from picking up a delivery. (“Who, me? Must be some other Frederick Forecastle.”)

In the New World, letters were delivered by any available means. They might be entrusted to a friend or family member going in the same general direction as the letter. They were carried by traveling merchants, ships’ captains, local Native American tribal members, or servants or slaves running errands—in other words, pretty much anyone who was on the road and headed in the general direction of one’s addressee. If they couldn’t be hand-delivered, they were often left at the closest tavern, to be picked up by a visitor who might know the recipient.

The first “official” post office was Fairbanks’ Tavern in Boston, named in 1639 by the British Crown as a collection site for mail between the colonies and England. William Penn set up a service for Pennsylvania in 1692. By the 1700s, several other locations had been designated throughout the colonies, as well as postal carriers who delivered mail among them. Roads were few, and pretty terrible. Some were existing American Indian trails. (The monthly post rider’s trail between New York and Boston, the Old Boston Post Road, is part of today’s U.S. Route 1.) People didn’t receive mail often, but it’s surprising that so many letters made it.

In 1737, Benjamin Franklin was named postmaster of Philadelphia by the British Crown, and in 1753 one of two postmasters-general for the colonies. As you might imagine, Franklin jumped in and made improvements, setting out on a post office inspection tour, surveying and shortening routes, and installing milestones. He also established a penny-post, streamlined accounting methods, and instituted night riders. The Crown dismissed Franklin in 1774, however, for his ornery revolutionary ideas. By that time, the postal service was operating from Maine to Florida and New York to Canada, on a regular schedule, and for the first time was making a profit. (The British government ought to have known they were in for trouble.)

As early as 1775, postal carriers operating under the Continental Congress were hired as persons of good reputation, sworn to lock and secure the mail they carried (which might sometimes have included inflammatory anti-British sentiments). After the war, the Continental Congress re-hired Franklin, making him the first official Postmaster General of the new United States.

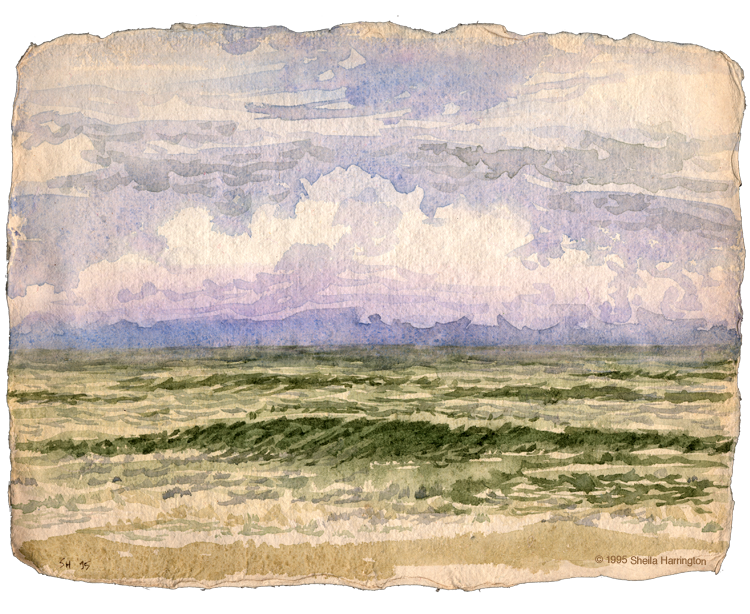

The development of the Postal Service has followed that of the nation, expanding in area served as new states were added. Mail has been carried by horseman, stagecoach, railroad, steamboat, truck, and pneumatic tube. (My mother, who grew up on a sheep ranch in Mendocino County, California, had the responsibility of going to “meet the stage” and fetch the family mail. Although it was by that time a truck, the family still automatically called it “the stage” because in her grandparents’ day it had been a horse-drawn stagecoach.) In 1918 the first airmail routes were established. How exciting, to receive mail that had actually FLOWN in an AIRPLANE, which very few citizens had ever experienced themselves.

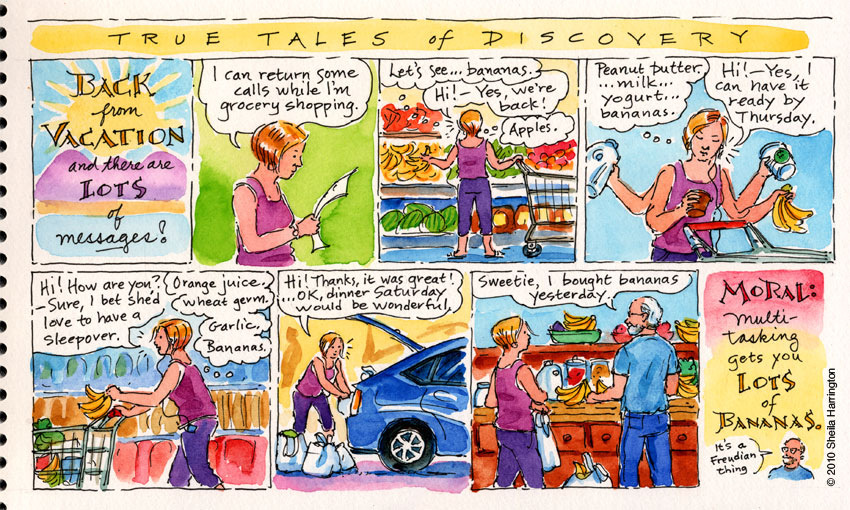

Today I can email messages and photos to family and friends living across the country and on other continents, and hear back from them within seconds. When our son studied abroad in Japan, we could sit in front of our respective screens and unwrap our Christmas presents together. This definitely has an Amazement Factor. However, praiseworthy though it may be, these are only ELECTRONIC IMPULSES and PIXELS, folks.

Picture this: your friend, who lives on the other side of the world, wraps a lovely gift and attaches a heartfelt handwritten note decorated with little stars and hearts. He/she (probably a she) takes it to the local post office, and in a few days your Friendly Neighborhood Postal Carrier, who trudges faithfully to your home day after day, year after year, through snow, rain, heat, and all the aforementioned, delivers it Personally into your Hands. Along with heaps of other real stuff too, like offers for credit cards, and Victoria’s Secret catalogues. Wow! Now that is what I call amazing. Think of this, and remember your postal carrier at the holidays. And take a moment to smile and thank your postal carrier, today and every day.