Continued from Library of Congress–Part 1, on April 24th

In its two-plus centuries, the Library of Congress has had a mere thirteen Librarians. They often serve a very long time, a sort of Library Supreme Court Justice. One of them was Archibald MacLeish (1892-1982), whose birthday it is today.

Born in Illinois, educated at Yale with a major in English, and at Harvard Law School, MacLeish might have had a straightforward uneventful law career, with writing and teaching as secondary pursuits, but for having served in the Army in World War I. Perhaps it was this wartime-planted seed that was sprouting when he left his law firm after three years and moved to Paris with his wife. There he spent five years writing poetry and drama and hanging out with the Hemingway-Fitzgerald-Pound crowd.

Well, how do you keep ’em down on the firm, after they’ve seen Paree. Instead of resuming his law practice after returning stateside, MacLeish continued to write, and to work for Fortune magazine. He had been, after all, an English major, and some of them do find employment—look at Garrison Keillor.

The anti-fascist viewpoint expressed in MacLeish’s writing drew the attention of President Roosevelt, who decided to appoint MacLeish as the next Librarian of Congress, over Republican Congressional opposition (“Expatriate!” “Communist!” “Poet!”). Professional librarians weren’t too happy about it either, since MacLeish was a Library World illegal immigrant. Once installed, however, he proved his skills and dedication, beginning with a major administrative reorganization of the rather uneven and semi-catalogued Library, clarifying its collection goals (Where are the holes to be filled?) and acquisitions policies (How can we fill them?), and requesting (and receiving!) a major expansion of Library budget and staff.

MacLeish also brought writers onto Library staff, launched poetry readings, wrote speeches for FDR, and much more which you can read about in detail on the Library’s website. Pretty amazing that he could accomplish all this in his 1939 to 1944 term, move on to serve as Assistant Secretary of State, then follow up with a writing/teaching career, winning Pulitzer Prizes for his drama and poetry, for which he is probably better-known.

The current Librarian, Dr. James Billington, has been a serious advocate of the National Digital Library Program, an ongoing project to digitize resources within the Library of Congress, making them accessible to that part of the world’s population (i.e., nearly everyone) which cannot make a personal visit to the physical Library in Washington, DC. In conjunction with this he proposed the creation of a multilingual World Digital Library, which was launched, with UNESCO, in 2009. Billington is a writer and a Russian scholar with a list of talents, awards, and accomplishments inside and outside the Library that is far too long to include here, but you can peruse his bio on the Library’s website, and then ponder sorrowfully how you yourself have frittered away your allotted time on this earth. Each Librarian brings his (so far it’s only been His) distinctive interests and talents to the post, thus enriching the Library.

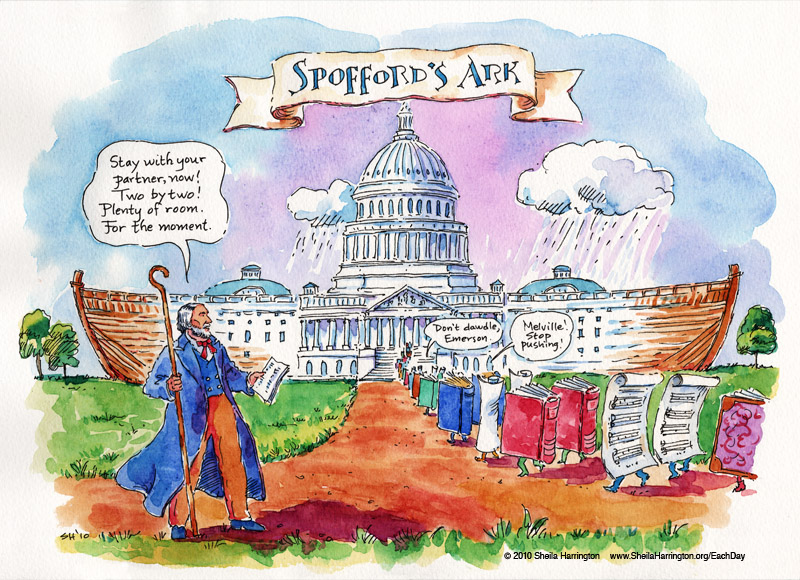

Possibly the best known Librarian of Congress—the “Father” of its modern incarnation—is Ainsworth Rand Spofford (served 1865-1897), who increased the Library’s collection dramatically AND acquired for it a new home.

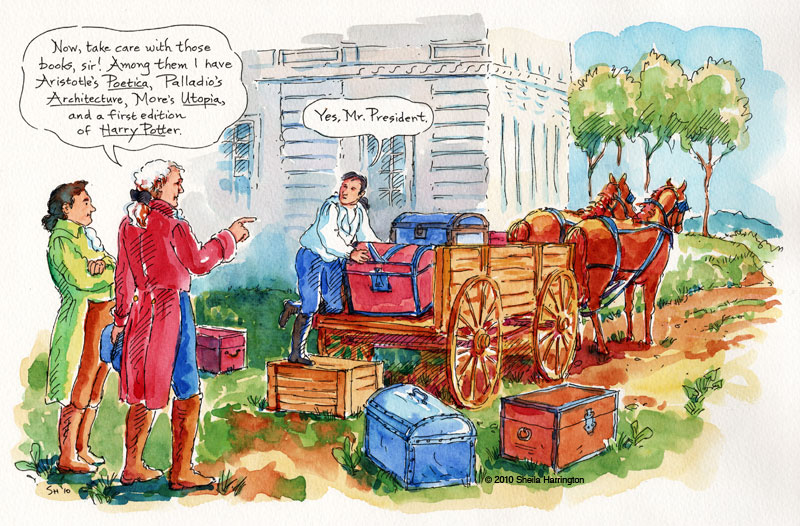

Spofford, born in New Hampshire and homeschooled (homeschoolers take note), was clearly headed for a life among books—avid reader, bookstore clerk, a founder of the Literary Club of Cincinnati, newspaper reporter and editor, and finally Assistant Librarian, then Librarian, of Congress. He managed to get the Smithsonian’s vast library transferred to the Library of Congress, and he persuaded Congress to pass a copyright law of 1870 that centralized all U.S. copyright registration at the Library—huge in itself!—and also required authors to deposit in the Library two copies of every book, map, print, and piece of music registered in the United States. (The copyright protection law extends even to works of foreign origin, with reciprocal protection. But there is apparently nothing the Library of Congress, or anyone else, can do about peculiar Chinese versions of Harry Potter that incorporate Chinese wizards, hobbits, and a belly dancer.) As you might guess, even if you have not a mathematical mind, such a law rapidly increased the Library’s collections.

A terrible fire on Christmas Eve, 1851, apparently due to a spark from an unattended fireplace, had, sadly, destroyed about two-thirds of the Library’s contents, including much of Jefferson’s original library. But the collection had been replenished in the 1850s, and by now the Library was stuffed to the gills. Over its history it had been moved around the Capitol, in and out of various spaces, to accommodate its growth. But the moment had come—the moment that we ourselves experience when we say, “I cannot put one more dishtowel into this kitchen drawer! We need to move!” And Spofford recognized that moment.