In honor of the birthday of Isadora Duncan (1877-1927) I post this sketch of my daughter in her ballet costume, drawn about 7 years ago. I was surprised to see how many quick sketches I had made over the years of my daughter dancing, in various costumes, trailing scarves and capes and, in one case, a large feather duster. I don’t think Isadora Duncan made use of feather dusters. However, she really did have a troupe of students named the Isadorables.

To Ellen, At The South

A May bouquet from my sketchbook.

Ellen, a poet herself, shares a birthday with Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) so it seemed appropriate to post this poem for the two of them today. Except that Ellen is actually At The North.

To Ellen, At The South

The green grass is growing,

The morning wind is in it,

‘Tis a tune worth the knowing,

Though it change every minute.

‘Tis a tune of the spring,

Every year plays it over,

To the robin on the wing,

To the pausing lover.

O’er ten thousand thousand acres

Goes light the nimble zephyr,

The flowers, tiny feet of shakers,

Worship him ever.

Hark to the winning sound!

They summon thee, dearest, Saying;

“We have drest for thee the ground,

Nor yet thou appearest.

“O hasten, ‘tis our time,

Ere yet the red summer

Scorch our delicate prime,

Loved of bee, the tawny hummer.

“O pride of thy race!

Sad in sooth it were to ours,

If our brief tribe miss thy face,—

We pour New England flowers.

“Fairest! choose the fairest members

Of our lithe society;

June’s glories and September’s

Show our love and piety.

“Thou shalt command us all,

April’s cowslip, summer’s clover

To the gentian in the fall,

Blue-eyed pet of blue-eyed lover.

“O come, then, quickly come,

We are budding, we are blowing,

And the wind which we perfume

Sings a tune that’s worth thy knowing.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

(Maybe by this time next year I can find one for Jeannie.)

Busy Beaver

From my sketchbook (drawn across the gutter; sorry).

On a Memorial Day weekend hike through beautiful Prince William Forest Park in Virginia a few years ago, we saw many tree stumps ending in chewed points, surrounded by piles of wood chips, indicating the presence of beavers. And when we reached the creek, we did see several beavers, as well as a substantial beaver dam. What I couldn’t understand was why the stumps were so FAR from the water. A mystery.

Prince of Binomial Nomenclature: Part 1

This is a drawing of Trifolium repens (Three leaves, creeping), otherwise known as white clover, from our Botany block. My daughter has been growing her very own patch of it in the garden, and it’s doing a lot better than the arugula.

I post this drawing because Trifolium repens was personally given its name by none other than…the Prince of Binomial Nomenclature.

Wouldn’t Prince of Binomial Nomenclature be an awesome title for a work of sophisticated tween fantasy literature? An unknown yet gifted Swedish youth—the future Prince—ventures forth into the wilderness, despite the objections of his parents, to make discoveries that change thenceforth the way we look at relationships among all living things on Earth, and founds the Grand Kingdom of Binomial Nomenclature.

This is actually a TRUE story. Today is the birthday of Carl, or Carolus, Linnaeus (1707-1778), who grew up in Stenbrohult, Sweden, in a village surrounded by farmland, woods, and mountains, a made-to-order environment for a future naturalist. But his father and grandfather were both country pastors, and they expected little Carl would follow in their footsteps, so his parents hired a tutor for his pastor-preparatory education.

Carl, however, showed from an early age a distinct inclination to wander off looking at plants. Exasperated, his family sent him away at age nine to a school in town, where classes ran from 6 am to 5 pm and consisted of studying Latin, Greek, and the Bible. Astonishingly, this did nothing to increase Linnaeus’ passion for school (although the Latin came in handy later, as we shall see). Often he skipped class to explore the fields, examining flowers. The only subjects he liked were logic and physics, taught by the town doctor, who lent him books and persuaded Linnaeus’ parents to let him become a doctor instead of a clergyman—this was an age when almost all medicines were plant-based, so knowledge of them was extremely useful—and offered him anatomy and physiology studies until he was ready for University. A doctor! What a crushing disappointment! But they reluctantly agreed.

Linnaeus enrolled first at Lund University, where his father had studied. No one there taught his real interest, botany, but he was befriended by a professor with botany books in his personal library, from which Linnaeus taught himself. When Linnaeus transferred to the University at Uppsala for its botanical gardens, his parents withdrew their financial support. You’re on your own, you little botanist.

So poor that he suffered from malnutrition and patched his shoes with paper, Linnaeus would have withdrawn from school if not for a fortunate meeting with a theology professor who was so taken with Linnaeus’ botanical knowledge that he offered him room and board and found him tutoring work. Grateful, Linnaeus thanked him with the gift of a paper he had written on pollination. Not your typical present (“Happy birthday! I wrote you a paper on pollination!”), but I guess he knew his recipient.

Why pollination? Well, Linnaeus was troubled by the popular methods of plant classification and had begun to ponder a new system. Classification of organisms was hardly a new concept, dating back at least to Aristotle, but naturalists differed on how it ought to be done, and several different systems existed. Was it to be by form? By function? By environment? (One system grouped beavers with fish, because both live in water. For a while the Catholic church permitted beaver to be eaten on fast days. That must have made the Jesuits’ work easier in North America.) What about the problem of naming? The same plant or animal was given a multitude of names in different countries. And what about the absolute flood of new, unfamiliar flora and fauna arriving from expeditions to the Americas? It was overwhelming.

Linnaeus’ paper explained a theory he had developed about the roles of stamens and pistils in plants. The professor, impressed, had it read at the Swedish Royal Academy of Science, and, although Linnaeus was still a student, he was offered a position as a botanical lecturer. His talks drew hundreds of listeners, many times the usual number. This was partly due to the controversial nature of the subject of plant reproduction (a new, hot topic) and partly due to Linnaeus’ unusually poetic and anthropomorphic descriptions of his plant subjects’ structure and habits. “The actual petals of the flower contribute nothing to generation, serving only as bridal beds,” he said. And, “It is time for the bridegroom to embrace his beloved bride and surrender his gifts to her.” That’s my kind of botany class! No wonder he brought in the crowds. Nowadays we can usually mention stamens in public without causing a shiver of excitement. (Correct me if I am wrong here.)

Please see Prince of Binomial Nomenclature: Part 2

Late Spring Cleaning

Secret potion

Here is friend and neighbor Tom, a brainy and funny guy who combines 21st century thinking with old-fashioned gentlemanly kindness. In honor of his birthday I am putting up this drawing of him from my sketchbook. Although it was drawn several years ago, Tom never seems to get any older. (What’s REALLY in that glass, anyway?) Happy Birthday, Tom. Perhaps you are already awake and having your morning Elixir of Youth.

Not Again

Eatin’ on the Beat

Crazy for Math

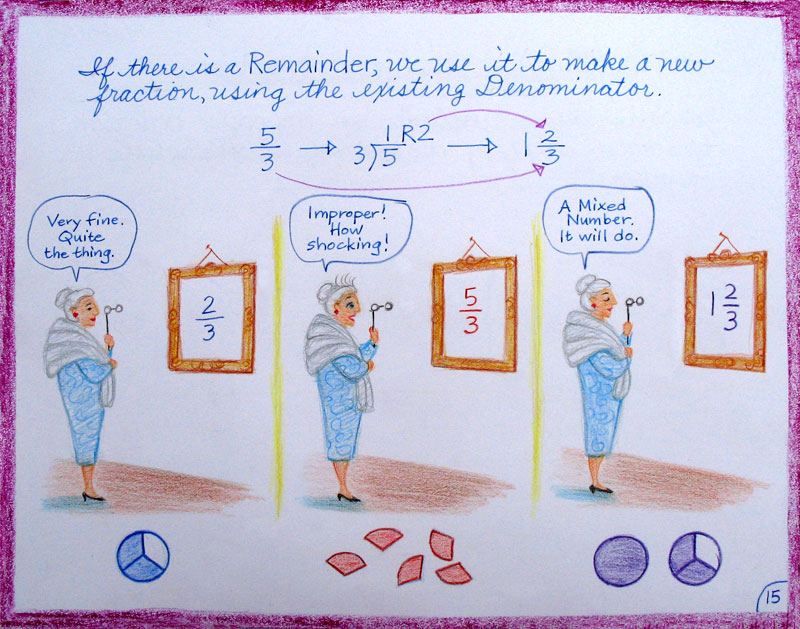

This is a page of the Improper Fractions lesson from our homeschooling Fractions block. I hope to get the entire book up on the Homeschooling page eventually. For now it serves as an introduction for what I am about to tell you.

Recently a big group of us had dinner at the home of our friends Lynn and Giovanni. The meal ended with everyone playing with math puzzles and games around the dining room table. Lynn, a Math Whiz, owns hundreds of them. For years she was a math instructor and tutor. Then in 1999 she developed a summer Math Camp called “MathTree.” It’s not only for kids struggling with math, but also for kids who can’t get enough and want it included in their summers. (I understand that there actually ARE such children, although none has shown up in my family.)

MathTree has taken off—that first summer there were two locations, and now there are 26 of them (!!!), for kids ages five to teens, all over the Washington metropolitan area. Lynn has developed a hands-on approach using objects, games, puzzles, and real-life experiences. (I was reading the fliers for the camp choices and thinking I might like to sign up myself! except they don’t have my age group.) If you are looking for an unusual kids’ math camp, MathTree might be just the ticket. So I’m putting a link to the website and brochure here. As my husband and I frequently remind each other, Someday Our Children Will Thank Us.

Library of Congress-Part 3

(If this picture is baffling, please see the news story on the Texas school board’s decision to eliminate Thomas Jefferson from its textbooks.)

Continued from Library of Congress–Part 2, May 7th

Spofford proposed a separate building for a library that would equal (or surpass! he suggested temptingly to Congress) the great libraries of Europe. It took about 15 years to hold a design competition and authorize funds, but at last, between 1886 and 1897, an astonishing team of architects, engineers, artists, and craftspeople created the Thomas Jefferson Building, probably the most magnificent structure in Washington, DC, and certainly the most labor-intensive per square inch.

The award-winning design was a building in the style of the Italian Renaissance, “efficient, beautiful, and safe,” and its thoughtful embellishment and finishing—despite a hovering Congress with its eye on the budget—is a suitable tribute to that period of cultural flowering. Stroll through and marvel at the multi-layered ornamentation, in paint, marble, and mosaic, depicting images and figures historical and mythological honoring the higher achievements of humanity: philosophy, natural science, music, art, theology, astronomy, law.

And these many wonders house a collection even more wondrous. Who could have foreseen, on that day in 1800 when John Adams signed the appropriations bill, what would develop from an initial purchase of 740 books and three maps? This is from the Library’s own website:

The Library of Congress is the largest library in the world, with nearly 145 million items on approximately 745 miles of bookshelves. The collections include more than 33 million books and other print materials, 3 million recordings, 12.5 million photographs, 5.3 million maps, 6 million pieces of sheet music and 63 million manuscripts… The Library receives some 22,000 items each working day and adds approximately 10,000 items to the collections daily… In 1992 it acquired its 100 millionth item.

Not only that, but at the Library you will find:

Works in 470 languages. Four Hundred and Seventy.

Newspapers in many of those languages, from all over the world.

Over 5,000 books printed BEFORE 1500, including a Gutenberg Bible.

Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, with Talking Books and other resources available free of charge.

The Center for the Book, created to promote literacy and reading, with affiliates in all 50 states.

The American Folklife Center, with 4,000 collections of stories, music, and oral history.

An ongoing program of lectures, symposia, exhibitions, concerts, book-signings, films, and tours both general and specific.

The Library of Congress also sponsors the popular annual National Book Festival on the Mall, bringing authors and readers together for readings and discussion.

Whew! And that’s not even all….for the rest of it you must go to the website to discover. Or to the Library itself.

The Library of Congress remains a work in progress, an almost unimaginable organizational, classification, conservation and retrieval challenge. Its evolution from modest beginnings is astounding. It has survived fires, civil and world wars, recessions and depressions, and an international information explosion.

And you, dear Reader, should you manage to make it to Washington, DC, and if you are at least 16 years of age (high school students must show that they have first exhausted their other sources for research) and have a valid identification card, such as a driver’s license: YOU are eligible for a Library of Congress Reader Identification card, and you may pursue your studies, with access to hundreds of years of accumulated knowledge and beauty, in the splendid Reading Room of this marvelous, this amazing, this thank-your-lucky-stars national treasure.