In looking through my sketchbooks I came across this drawing made ten years ago (!!!) of the daughter of old friends (and now a grown-up friend herself)—the delightful, smart and multi-talented Hallie, whose birthday it is today. Here she is diligently, and characteristically, doing her homework. Happy Birthday, Hallie! I hope you have raspberries and whipped cream for breakfast.

Come, Lovely May

Here are the lovely grounds of the neighborhood Marriott Wardman Park hotel before they cut down most of the trees. Sigh. My daughter was skipping along, filling a basket with fallen blossoms.

Come, lovely May, with blossoms

And boughs of tender green,

And lead me over the meadows

Where cowslips first were seen.

For now I long to welcome

The radiant flowers of spring,

And through the wild woods wander,

And hear the sweet birds sing.

—Traditional

Sorry…

Weaving Workshop

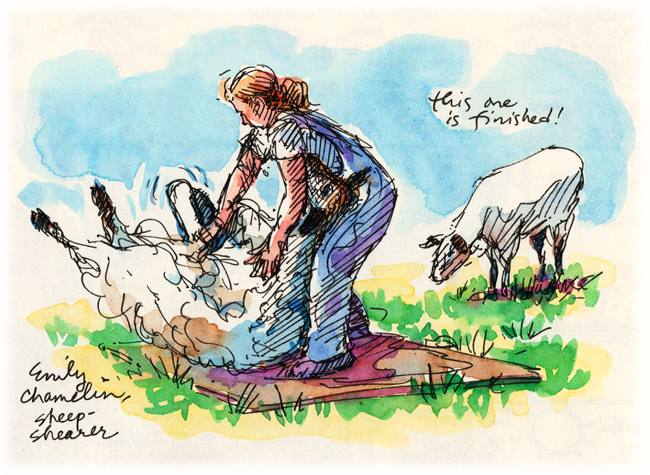

Sheep-Shearing

A speedy fleecing at the Sheep and Wool Festival in Howard County, Maryland.

This image is now available as an 8.5″ x 11″ archival high-resolution print.

Happy May Day

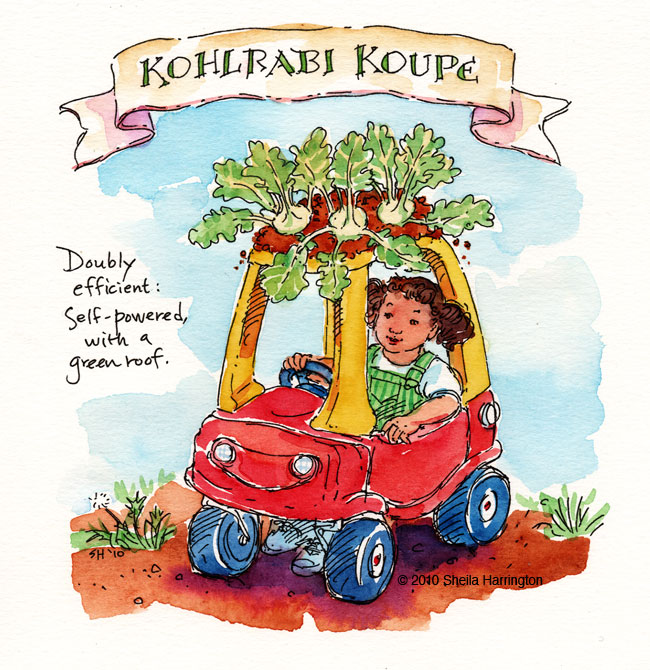

Energy-Efficient Vehicle #4

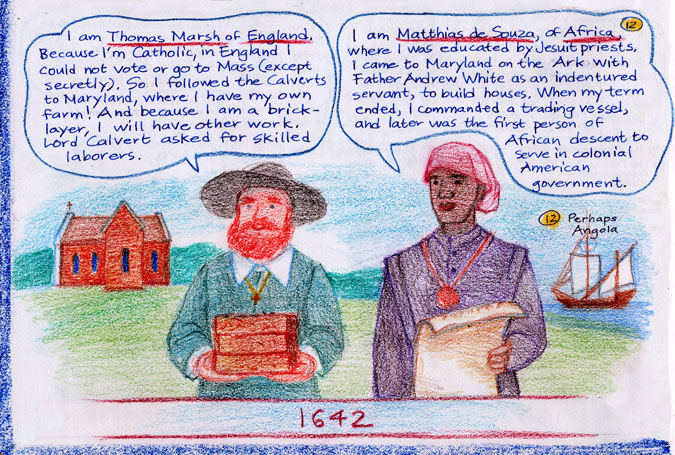

Maryland Part II

Continued from April 28th, Part I.

Pictures are from our homeschooling block, Local History and Geography.

Despite Maryland’s absence of gold, colonists benefited from another resource: tobacco, which grew well and had a ready market in England. It quickly became Maryland’s principal cash crop. (In rural areas tobacco was used to pay bills even into the 20th century.) Some planters made large fortunes and imported their style of living from England, spending their time at hunting meets, dances, card parties, horse races, and similarly useful pursuits.

Tobacco rapidly depleted the soil, however, requiring continual acquisition of acreage and labor, both hired and slave, and pushing Native Americans further from their homelands. In the first half of the 18th century, England helpfully sent 10,000 convicts, mainly petty thieves and other troublesome folk, to Maryland as indentured servants. But while they worked off their indentures and freed themselves, the slave population, permanently trapped, increased. (And that’s another story.)

Maryland’s coastlines were settled first, so when German and Scotch-Irish immigrants began to arrive in the 1740s, they moved into western Maryland, creating small farms like those in Europe and New England, raising animals, growing grains (rather than tobacco) on manured fields, rotating their crops, and feeling exasperated that large wasteful eastern plantation-holders had more say in land and trade policy than they did themselves. Iron was discovered in western Maryland, and its mining and forging, mostly by slaves, accelerated rapidly. The port of Baltimore grew as grain and iron passed through for the French and Indian Wars, warfare being ever a boon to industry. Annapolis very slowly became a center of society, acquiring the attendant accoutrements of high culture: a theater, newspaper, bookshop, and jail.

By the 1770s, the now-numerous settlers (Maryland’s population was about 150,000, which included tens of thousands of African slaves and a few hundred remaining Native Americans) were inevitably, due to time, distance, and differences, less connected to Great Britain. In 1713 the currently reigning Calvert had converted to Protestantism. But Marylanders didn’t want ANY Proprietor, of any religion whatsoever. Parliament’s taxes and trading practices favoring Great Britain infuriated them, as it did colonists elsewhere. Although some were at first unsure about complete independence, Maryland sent delegates to the First Continental Congress in 1774. Four signers of the Declaration of Independence were from Maryland, including the only Catholic. Maryland militiamen fought with George Washington in the Revolutionary War (the state’s sole Tory regiment was chased across the border and later departed for Canada).

After the war finally ended in 1783—people forget how LONG it dragged on—and after the delegates to the Constitutional Convention spent the summer of 1787 heatedly wrangling over the creation of the Constitution (which story reads like a thriller in itself), Maryland ratified it the following spring, becoming the seventh of the new United States. Not only that, but Maryland provided two of the nation’s seven temporary capitals (Baltimore and Annapolis) throughout its formative years, and finally the permanent one in 1790: Washington, District of Columbia, carved from a 10-mile square on the Potomac. (Virginia took back its section in 1846.)

So, party down, Marylanders! and celebrate your stateliness by singing the Official State Song (to the tune of “O Tannenbaum”). Here are the first two verses. Just in case you don’t already know them by heart.

The despot’s heel is on thy shore,

Maryland!*

His torch is at thy temple door,

Maryland!

Avenge the patriotic gore

That flecked the streets of Baltimore,

And be the battle queen of yore,

Maryland! My Maryland!

Hark to an exiled son’s appeal,

Maryland!

My mother State! to thee I kneel,

Maryland!

For life and death, for woe and weal,

Thy peerless chivalry reveal,

And gird thy beauteous limbs with steel,

Maryland! My Maryland!

* Although the words as written, and as adopted by statute, contain only one instance of “Maryland” in the second and fourth line of each stanza, common practice is to sing “Maryland, my Maryland” each time to keep with the meter of the tune.

Maryland, My Maryland

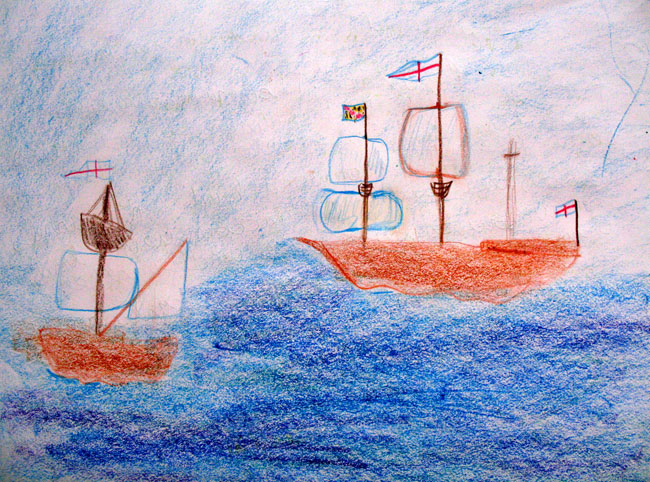

Pictures by my daughter from the Local History and Geography homeschooling block.

On this day in 1788, Maryland became the 7th state to ratify the Constitution. Perhaps you live in Maryland and never knew how this came about. Or perhaps Maryland is terra incognita because you live far away, in Nepal, or Virginia. In any case, I am going to tell you.

For thousands of years human beings on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay fished, farmed, and fought one another without foreign interference. However, the seagoing vessels across the Atlantic Ocean grew ever-larger, and when Italian Giovanni Caboto, in the pay of Henry VII of England, wandered into codfish-rich Newfoundland/Maine waters in 1497, that was enough for England to claim the promising land. (They also insisted on referring to Caboto as “John Cabot” to help make their case.)

One hundred and ten years later Captain John Smith, although mainly concerned with the floundering colony in Virginia, ventured up the Chesapeake Bay, pronounced it goodly and pleasant, and produced a map that received much attention. So when George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore, tired of the anti-Catholic feeling in Protestant England (Catholics were considered untrustworthy and could not hold office, vote, or worship openly), he asked his friend King Charles I to give him a piece of this New World land.

Calvert had tried Newfoundland first, but his settlers died of harsh weather and disease. His request was granted, but the Virginians were unhappy about the potential nearness of Papists. Well, suggested Charles, how about just a northern sliver of Virginia, about 10,000 square miles around the Chesapeake Bay—nobody there except non-Christian native dwellers! Calvert accepted this parcel, to tax and govern as he saw fit, in exchange for two Indian arrowheads a year, an enviably low rent.

Shortly afterward George Calvert died, so his younger son Leonard set sail in the Ark and the Dove and a party that included settlers and adventurers, several gentlemen, a handful of women, a number of indentured servants, and three priests. The group was a mixture of Catholics and Protestants, as it was Calvert’s intention to set up a religious-tolerant community. When they arrived at the mouth of the Potomac in March 1634, they were kindly greeted by the surprised yet helpful Yaocomico inhabitants, who, tiring of attacks by their Susquehannah neighbors, were fortuitously planning a move west. They granted the newcomers their land, along with houses, fields, and useful botanical, zoological, and culinary tips. The settlers renamed the territory Terra Maria, in honor of Queen Henrietta Maria (daughter of King Henri IV of France). Terra Maria: Mary-Land.

The Maryland settlers were better prepared than their hapless predecessors in Jamestown, those aristocratic younger sons who arrived in their best clothes ready to pick up the gold and jewels lying scattered on the shores of America. No, these folks brought tools and seeds and useful skills like carpentry, and had been recruited by Calvert on condition of willingness to work hard. The village, now called Saint Mary’s City, Maryland’s capital, was quickly fortified and the surrounding lands divided and allotted according to size of the household living on it: for heads of household, wives, and indentured servants, 100 acres each; for children 50 acres each. You can imagine that this arrangement encouraged emigration of large groups. “And here is my cousin Robert… and his son John…and their three manservants…” Voilá—450 more acres!

Although the Calverts were Proprietors—they actually “owned” Maryland and could govern it as they saw fit—the settlers announced that they intended to make their own laws. Calvert objected, and an uneasy compromise was worked out, but this insistence on self-rule was, as we know, a harbinger of things to come. Calvert did convince them to pass his Act of Toleration in 1649, which guaranteed religious freedom to Christians, although the arrangement was: if you deny the divinity of Jesus Christ you will be executed. Such means of ensuring uniform worship have not entirely fallen out of favor in 2010. The Act lasted until the Puritans chopped off Charles I’s head for tyrannical cluelessness (no longer a capital offense in Great Britain). In 1692 England and its colonies were declared officially Protestant. The new leaders burned down the Catholic churches in Maryland and moved its capital to Puritan-founded Providence—renamed Annapolis for Protestant Queen Anne.

To be continued April 29th: Part II.