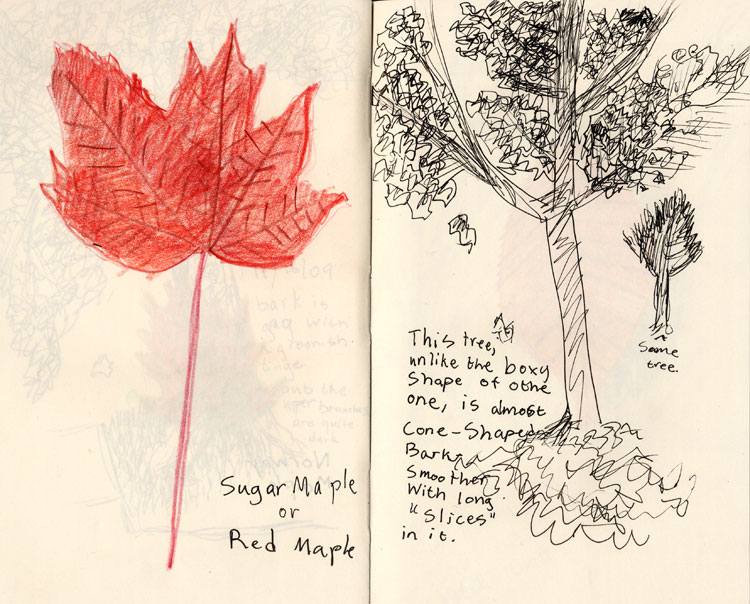

Another neighborhood tree sketch, this one by my daughter. If this IS a sugar maple, does that mean we could be tapping trees right here in Woodley Park, DC?

Tag: DC

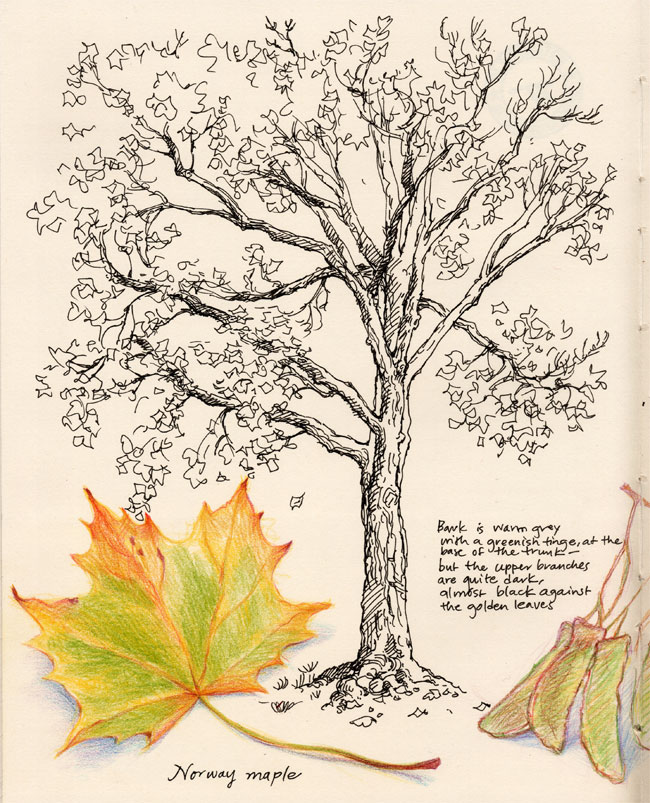

Norway Maple

Young at Art

The National Gallery of Art sponsors a host of programs for school groups, families, and young children, hoping to inform and inspire the next generation of art-lovers, and we have availed ourselves of a number of them. From my sketchbook I post a visit made some years ago with my daughter for a program in the “Stories in Art” series, during which an NGA docent reads aloud a story, tours the museum discussing with the children paintings relevant to the book, and then leads them in a hands-on art project, which might be drawing, painting, sculpture, printmaking, collage. On this occasion, the children listened to the delightful story The Cow Who Fell in the Canal (Phyllis Krasilovsky/Peter Spier), toured the collection of 17th-century Dutch and Italian paintings of waterways, and then painted their own landscapes.

Skywatcher

If you lived in 17th century England and were found guilty of stealing, consequences could be severe: whipping, branding, a term in the pillory, even hanging. An alternative was transportation to the New World and seven years of indentured servitude. The colonies needed laborers.

For some people what was essentially permanent exile might have seemed worse than hanging. But it apparently worked out well for one Molly Welsh, a dairymaid who was transported and indentured to a Maryland tobacco planter in 1683 when she was found guilty of stealing, or at least knocking over, a pail of milk. It was a life-changing accident. After working a seven-year term, Molly had earned enough to buy a tobacco farm of her own, and bought a slave named Banneka (or Banneky) to help work it. Although interracial marriage was illegal at the time, love triumphed. Molly freed Banneka; the two were married and had four daughters.

One of their daughters also fell in love with a slave, so her parents bought his freedom to enable them to marry. Because like many slaves he had no surname, when they married he took their name (now Banneker) as well. And these were the parents of Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806), whose birthday it is today.

Benjamin was from all accounts a very bright child. His grandmother Molly taught him to read and write, and he was eager to learn from any available source. But books were few. Around 1770, three Ellicott brothers from a large Pennsylvania Quaker family built a mill, homes, and store nearby, which eventually became the hub of a prosperous community (now Ellicott City). The Ellicotts and their offspring were mechanically inclined and enjoyed experimenting with mechanical and scientific inventions. The family befriended their knowledge-hungry neighbor Benjamin and lent him books, tools, and a telescope.

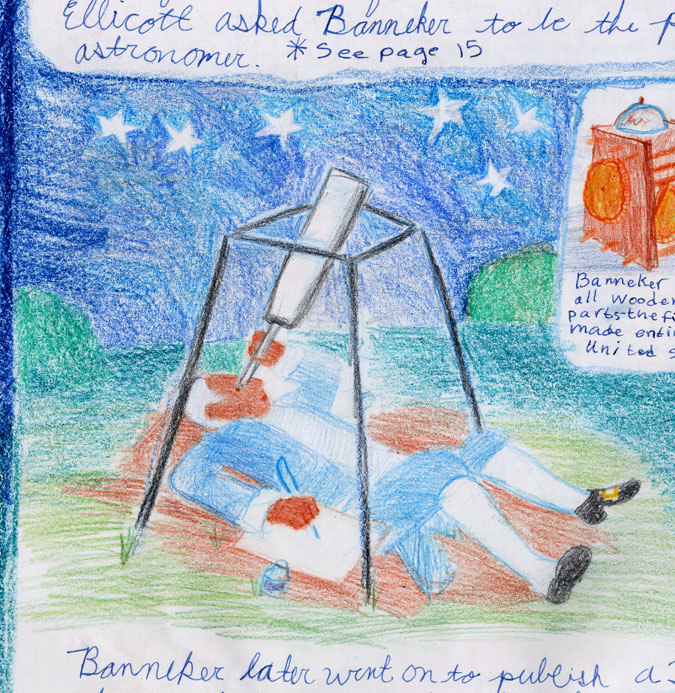

From that moment Banneker was devoted to astronomy, which he taught himself from the books and from studies of the night sky he made (in addition to carrying on the work of the family farm). He became so skilled that in 1791, when Andrew Ellicott, who had helped complete the Mason-Dixon Line survey, was hired to survey the land for the nation’s new capital city, he asked Benjamin Banneker to help him with the necessary astronomical observations. It’s pretty rough spending your nights outdoors for months stretched out on the cold ground measuring the stars when you’re 59 years old, but Banneker agreed. (This is the scene depicted above in my daughter’s Main Lesson book from our homeschooling Local History and Geography block.) So off they went to lay out the boundaries for the ten-by-ten-mile square that was to become Washington, DC. Some of the original boundary stones are still visible.

In the course of this project Banneker grew ill and was obliged to retire to the farm. But he was undeterred from his studies, and by 1792 he had created and published an almanac that included forecasts of weather, tides, eclipses and other movements of heavenly bodies—all calculated by Banneker—as well as festival days, essays and poetry (including work by Phillis Wheatley), instructions for home medical care, and Banneker’s views on free public education and religion.

The almanac was distributed in four states and went through several editions, one of which included an exchange of correspondence between Banneker and Thomas Jefferson, then serving as Secretary of State under George Washington. Banneker pointed out in his letter the irony of Jefferson’s having stated in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal” while simultaneously “detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren, under groaning captivity and cruel oppression.” In Jefferson’s polite and complimentary response, however, he avoids addressing this conundrum in his life, as he adroitly managed to do whenever it was mentioned.

Abolitionists in the colonies and Great Britain were thrilled with the almanac as another piece of evidence for the immorality—in fact, the downright senselessness—of slavery. Happy Birthday, Benjamin Banneker. Your work is another milestone on the road to freedom.

Heavenly Strings

One of the numerous advantages of homeschooling is accompanying one’s children on field trips. Recently we attended a performance by amazing violinist Karen Briggs and her back-up combo. The concert, one of a series organized for school groups, was held in the Kennedy Center’s Jazz Club, which is set up with cafe tables and chairs rather than rows of seats, and intimate enough that Briggs could chat with us informally between pieces (and that I could see her well enough to sketch). She played for us a range of pieces, and her fiery interpretations and improvisations, drawing on classical, jazz, gospel, African, and Middle Eastern traditions, mesmerized and dazzled the audience, many of whom, it turned out, were young violinists. Briggs has played in concert halls all over the world and is probably best known for her work with keyboard artist Yanni. We all departed with stars in our eyes.

Boooo!

Here’s an art form I don’t use too often but which comes in handy for large-scale decorating in a hurry—big white paper cutouts. This is our frightening Halloween front door, featuring the ghost family: Dad with mini-version of boat he is building; Sis with energetic jump-rope; Bro with faithful iPhone; Mom with paintbrush and spoon; and the world’s least scary Dog, unless you fear relentless licking.

United Nations Day

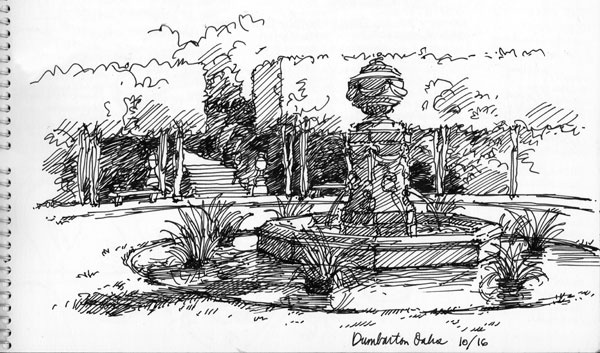

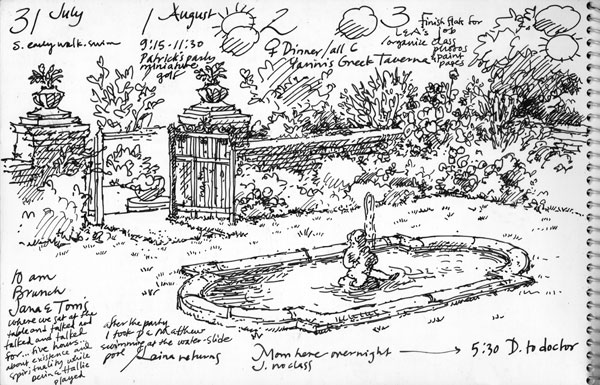

These drawings are from a couple of sketchbook-journals carried on visits to the beautiful gardens of Dumbarton Oaks in Georgetown, Washington, DC. However, I post them not for the sake of those lovely gardens themselves (to which the sketches don’t do justice) but in honor of today’s anniversary of the ratification of the charter for the brand-new United Nations. Perhaps some of you folks out there already knew that the foundation of its charter had been hammered out at Dumbarton Oaks. I only learned it recently.

Dumbarton Oaks, built in 1801 as a private home, was purchased in 1920 by diplomat Robert Bliss and his wife Mildred. With Beatrix Ferrand they created the fabulous gardens and renovated the house, adding a music room for concerts and lectures, and a museum for their art collection. In 1940 they gave the property to Harvard University.

Although in 1940 the United States had not yet even officially entered the Second World War, entities private and governmental were already discussing the possible creation of a post-war international peacekeeping organization—but secretly, because of the strong isolationist, anti-League of Nations element existing in the country. Isn’t it amazing what significant matters we managed to keep secret in a pre-Internet era?

FDR first offered the optimistic term “United Nations” to refer to such an organization in a 1942 Declaration composed at the Arcadia Conference by the USA, the UK, the USSR, China, and twenty-two other countries to lay out their common goals during and after the war. Other nations signed on later. Bliss, speaking for Harvard, offered the use of Dumbarton Oaks as a possible location for future talks. This setting was deemed suitable, and the offer was accepted.

So, between August and October, 1944, representatives of the USSR, the UK, the USA, and China (although never with the USSR and China at the same table at the same time!) gathered at Dumbarton Oaks to wander the lawns, dine in the Orangery, and sit in the music room for a series of discussions. At their conclusion, the four nations had agreed upon a series of proposals which, along with provisions born of the Yalta conference, formed the basis for the new United Nations Charter, which was signed in San Francisco on October 24th, 1945.

Among the goals were these: The development of friendly international relations. The strengthening and maintenance of international peace and security. The removal of threats to peace through collective cooperation. And collective measures to solve economic and humanitarian problems.

What an impressive and inspiring global perspective, especially for a species that only a few thousand years earlier routinely regarded an unfamiliar tribe as the enemy. (This antiquated response is occasionally observed even now.) May we see these goals one day fully realized.

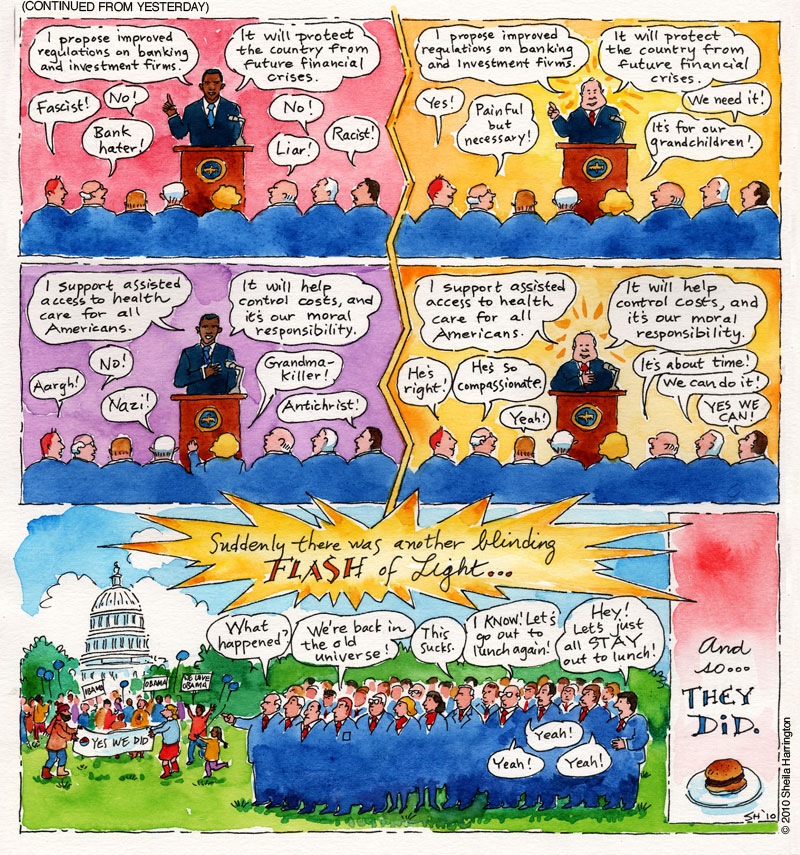

Alternate Universe Part 2

Please see October 19, 2010 for Part 1. Click on the image twice to see it full size.

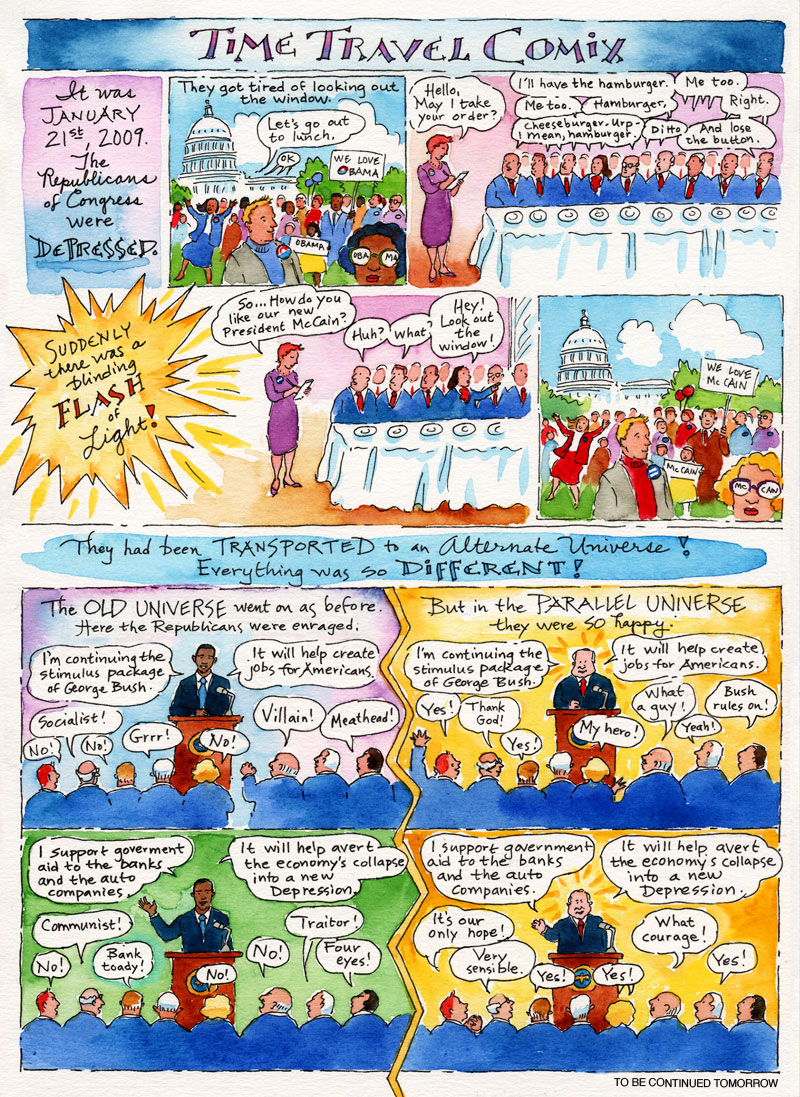

Alternate Universe Part 1

Justice of the Peace

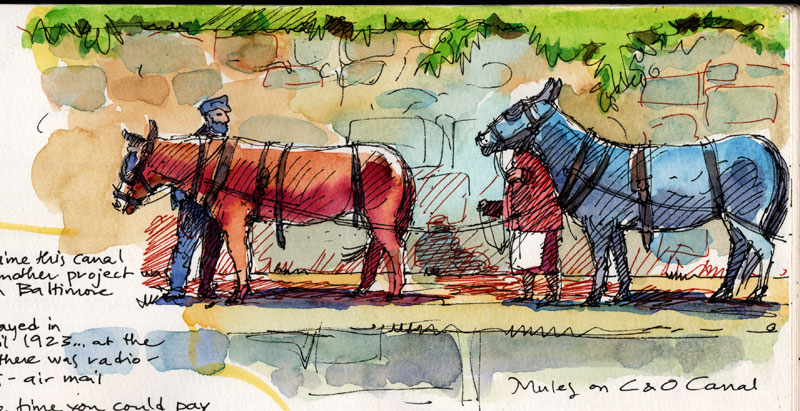

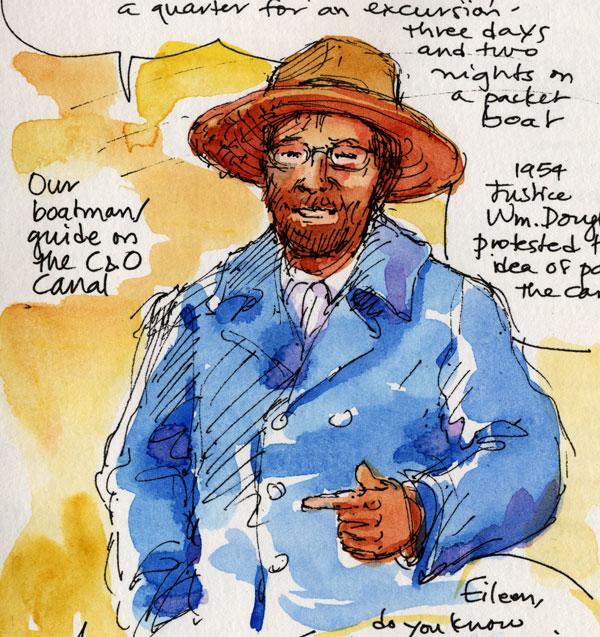

This sketch is from a canal barge tour we took on the C&O Canal as part of our homeschooling Local History & Geography block. It was mid-week, and my daughter and I were the only non-senior citizens on the trip, so she was definitely the focus of kindly attention (being small and cute with long blond braids), which was fine with her. The restored barge was beautiful, the costumed guide was excellent, the mules were friendly, and it was a lovely day.

ANYWAY, I post the sketch in honor of Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas (1898-1980), whose birthday it is today. What, you may ask, is the connection?

Well, some of you may know that Douglas, in addition to serving for 36 years on the Supreme Court, was an avid outdoorsman and supported various environmental causes, even serving briefly on the board of the Sierra Club.

In the 1950s, an era newly keen on the divine glory of automobiles and expanses of concrete pavement, there was a movement in Congress, supported by The Washington Post, to replace the canal with a highway. Douglas, familiar with the canal’s scenery and wildlife, thought this an idiotic and short-sighted idea and challenged the Post’s editorial staff to accompany him on a hike of the canal’s entire length.

Douglas expected that perhaps a handful of folks might accompany him; however, news of the challenge spread, and by the departure date there were 58 in the group, including conservationists, historians, geologists, ornithologists, and zoologists. Each night when they crashed, the group had a free, informative lecture, offered by one of their traveling companions, on some aspect of the canal.

Word got around, and thousands of newspapers carried updates on the hikers. Organizations along the way hosted them and prepared meals. Children and townspeople watched for them and shouted their support. Some joined in for parts of the route.

Even given the ongoing attention, it was a tough hike. The C&O Canal is 185 miles long, and Douglas, age 55, maintained an average pace of 23 miles a day. This was a man who had, after all, hiked the 2,000-mile Appalachian Trail. Only eight of his companions made it to the end. By then, public support to save the canal was enormous. Douglas organized and worked with a committee to plan its restoration and preservation, and The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Act finally passed in 1971.

Canal-lovers, imagine this place as a highway! Today it’s one of the most popular national parks in the U.S., enjoyed by millions of hikers, boaters, bicyclists, and birdwatchers. Not to mention the birds themselves, as well as countless fish, frogs, beaver, fox, and deer. Happy Birthday, Justice Douglas! We have you to thank for this gift, all year round.